We’ve implemented some new protocols around sending us messages via this website. Please email website “at” britishfantasysociety “dot” org for any issues.

For all things fantasy, horror, and speculative fiction

-

Announcement:

Subgenre deep dive: Sword & Sorcery

In this second edition of her new regular column, Tiffani Angus—co-author of Spec Fic for Newbies—takes us on a dive into the world of Sword & Sorcery.

Subgenres overlap in stories; just last weekend at a Christmas get-together, two friends had a back-and-forth about a horror film. One insisted it was body horror and the other one wasn’t having it, despite the film containing elements of the subgenre. As the one person in the room who had co-authored a book about subgenres, I just held my tongue (better not to wade into a family convo!). Most stories aren’t absolutely ONE subgenre and contain elements from other adjacent subgenres. Sword & Sorcery is one such subgenre that’s difficult to pin down completely because it’s evolved from its inception, and because high or epic fantasy often contains swords as well as sorcery.

As always, the information in this article is more fleshed out (and contains cross references to other subgenres as well as activities and other practical writing-specific instruction and information) in Spec Fic for Newbies: A Beginner’s Guide to Writing Subgenres of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror (Luna Press, 2023) by Val Nolan and me.

Get £3 off Spec Fic for Newbies when you buy directly from Luna Press using the promo code “SFN1”.

This month is a look at SWORD & SORCERY.

How is this subgenre, which contains both swords and sorcery—elements found in most high or epic fantasy—distinct from those subgenres? Think of it as a cousin, one of those faces in an old sepia-toned photograph that gets passed around at family reunions: everyone’s heard of Cousin Ernest, and he looks just like Uncle Hamish, but nobody can remember whether he’s a second or third cousin once or twice removed.

Sword & sorcery (S&S) shares a lot of creative DNA with other fantasy subgenres but distinguishes itself with a narrower focus; instead of a rag-tag crew roaming across the secondary-world landscape on a common quest, S&S usually features a single warrior character, sometimes with a sidekick, fighting supernatural creatures or beings for money or other personal motivation. This usually isn’t an “end of the world” scenario, and, unlike a lot of high fantasy, it can contain a bit of wry humour. S&S stories also tend to be episodic, with its tales mostly sticking to short stories or novellas rather than door-stop tomes. Though, of course, there are always exceptions!

We can trace this subgenre’s roots back to some of our oldest tales of myths and legends, such as Beowulf, and up to more recent swashbuckling stories such as Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers (1844). Despite such significant literary roots, S&S hasn’t earned much respect in wider circles, likely due to its birth as a product of the popular pulp magazines and publishers in the twentieth century, such as Weird Tales (1923–present) and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction (1949–present), which earned the moniker “pulp” because the paper was made of inexpensive wood pulp, which resulted in a belief that what was printed on it was as cheap and temporary.

We love our pulp heroes, though, with their singular look, (sometimes) humour, and focus. The S&S hero really developed from the 1930s–’60s, but not in a direct straight line. Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian stories (also known as Conan the Cimmerian, linking the character to a nomadic people from seventh-century Asia) began the subgenre in the 1930s, but his early death brought that S&S hero’s exploits temporarily to an end.

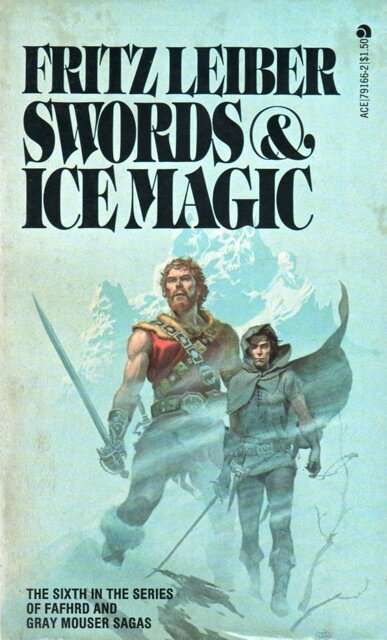

Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, spanning the 1930s to the 1980s, gave the subgenre a longer life; in fact, it’s Leiber who coined the subgenre’s name. C. L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry, featuring a female warrior, is another S&S example from the 1930s. It’s easy to see the link between this early S&S and the men’s adventure stories of the 1940s, when technology meant that everywhere on Earth had been “discovered” and explored but some people still dreamed of mysterious, unknown places being found and, dare we say it, conquered by strong, solitary Western men.

S&S kept on growing and evolving through the twentieth century, however. The development of interest in space led to the growth of “Planetary Romance” or “Sword & Planet” stories from the 1930s to the 1950s. The John Carter of Mars stories by Edgar Rice Burroughs (1917–’22), though early, are one of the most popular, but the reality of the desolation of other planets put an end to the popularity of this SF version of the subgenre in the 1960s, and S&S tales turned their attention back to secondary-fantasy worlds. Fantasy itself was experiencing a surge in popularity, partly due to the publication of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings in mass-market paperback in 1965. Also, Lancer Books published Howard’s Conan tales in novel form in the second half of the 1960s, leading to newer S&S tales, as well as a growing number of parodies, partly due to the attitudes toward the popularity, speed, and inexpensive publication materials (pulp). Then, in 1970, Leiber won a Hugo and a Nebula for his Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser novella Ill-Met in Lankhmar, further cementing S&S’s renewed vitality among readers and critics. The popularity of anthologies—in many ways the cultural memory of SFF/H—played a significant role in S&S’s status as a going concern. The Swordsmen and Sorcerers’ Guild of America (SAGA), active from the 1960s–’80s, created the Flashing Swords! anthologies between 1973–’81. More recently, Titan Books began its Heroic Legends series in 2023 with a new set of Conan tales penned by Stephen Graham Jones and John C. Hocking.

Outside of books and magazines, other media supported the growth of S&S. In the 1970s, Dungeons & Dragons arrived, helping the subgenre survive by giving players the opportunity to take on the role of a sword-wielding warrior battling monsters, and various SFF authors have cited it as an influence. But it was the arrival of cable television and home video—along with action figures for the various IP—that was the catalyst for another S&S revival, though not necessarily one with much gravitas.

Arnold Schwarzenegger started his path to becoming a household name as the title character in Conan the Barbarian (dir. John Milius, 1982) and its sequels. Conan wasn’t the only S&S hero on the tube. Anyone who grew up in the ’80s with early cable saw The Beastmaster (dir. Don Coscarelli, 1982), about a man with the power to communicate telepathically with animals. It was aired so much on television (so, so much; I must have watched it a dozen times!) that the joke was that the initials for the American cable station Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) stood for The Beastmaster Station; the other pop-culture jab was that HBO (Home Box Office) really stood for “Hey, Beastmaster’s On!”

Yet, while history might indicate is that this is a subgenre by and for White cis-het men (the language in the Conan stories definitely show that Howard was “of his time” in how women or non-white people are described), that’s not the case anymore. For example, C.J. Cherryh’s Morgaine Cycle series (1976–’79), features a female lead and mixes S&S with SF; Jen Williams’s Copper Cat trilogy (2014–’16) stars a female thief, a gay mercenary, and a Brown nobleman with a disability; and Elizabeth Bear’s The Stone in the Skull (2017) follows a unique mercenary on a journey through dangerous lands. Saladin Ahmed’s Throne of the Crescent Moon (2012) is set in a fantasy world inspired by the Middle East, while African-American author Charles R. Saunders’s Imaro trilogy (1981–’85) features a Black protagonist’s adventures in a secondary world based on Africa. Saunders also coined the term “Sword and Soul” to describe this new subgenre of S&S tales with an African influence.

Sword and Sorcery gives readers the chance to engage with a subgenre, originally linked to a particular historic time, that has evolved as the world has changed to feature a more diverse cast. With its mostly episodic nature it gives writers the chance to set aside extensive levels of worldbuilding and explore character building in shorter stories or novellas without losing any of the fun of fantasy tropes and elements. Its longevity also proves that we love a hero (or heroine!).

Some Recommended Reading

- Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter of Mars: The Collection – A Princess of Mars; The Gods of Mars; The Warlord of Mars; Thuvia, Maid of Mars; The Chessmen of Mars (2010)

- Robert E. Howard’s The Complete Chronicles of Conan; Centenary Edition (2006 hardback) or Conan the Barbarian: Complete Collection (2020 paperback): note that some collections have stories organised by publication date rather than story chronology.

- C.L. Moore’s Black God’s Kiss (2015): a collection of the six 1930s Jirel of Joiry tales

- Fritz Leiber’s Ill-Met in Lankhmar (1970)

- C.J. Cherryh’s Morgaine Cycle series (1976–’79)

- Charles R. Saunders’s Imaro trilogy (1981–’85)

- Saladin Ahmed’s Throne of the Crescent Moon (2012)

- Jen Williams’s Copper Cat trilogy (2014–’16)

- Elizabeth Bear’s The Stone in the Skull (2017)

Photos by Ricardo Cruz, Gioele Fazzeri, Clint Bustrillos and yoo soosang on Unsplash

Meet the author

Tiffani Angus (PhD), a BSFA- and BFS-award finalist for her debut novel Threading the Labyrinth, is also an ex-academic and the co-director of the Underhill Academy for SFF Writers. Her latest non-fiction book, co-written with academic and author Val Nolan and out with Luna Press, is Spec Fic for Newbies: A Beginner’s Guide to Writing Subgenres of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror. She lives in Bury St Edmunds and is currently at work on Spec Fic Vol 2, a novel, a novella, a short story collection, and another scandalous new project.

Explore the blog:

Blog categories:

Latest Posts:

Tags:

#featured (56) #science fiction (25) Book Review (264) events (44) Fantasy (231) Graphic Novel (13) horror (136) Members (62) Orbit Books (48) profile (43) Romance (17) Science Fiction (50) short stories (28) Titan Books (52) TV Review (15)

All reviews

Latest Reviews:

- THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND by William Hope Hodgson

- Monstrum by Lottie Mills

- Mood Swings by Dave Jeffery

- Yoke of Stars by R.B. Lemberg

- Hera by Jennifer Saint

- The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness

- RETURN OF THE DWARVES By Markus Heitz

- Delicious in Dungeon

- Toxxic by Jane Hennigan

- THIS ISLAND EARTH: 8 FEATURES FROM THE DRIVE-IN By Dale Bailey

Review tags:

#featured (2) Action (4) Adventure (4) Book Review (28) Fantasy (18) Featured (2) Feminist (2) Gothic Horror (3) Horror (14) Magic (3) Orbit Books (3) Romance (6) Science Fiction (5) Swords and Sorcery (2) Titan Books (7)

One response to “Subgenre deep dive: Sword & Sorcery”

I think Sword & Sorcery is best defined by what it is not, specifically Epic Fantasy. Hence the ‘Low’ fantasy tag. So while LOTR is a doorstopper about an epic struggle between good and evil and the good characters act in a suitably heroic way, Sword and Sorcery is – as you say – episodic, the characters are generally anti-heroes (thieves, mercenaries etc) and the stakes are pretty low.