This Qingming, or “Tomb-Sweeping Day”, the day every year when Chinese families visit the tombs of their ancestors to clean the gravesites and make ritual offerings to ancestors. Xueting C. Ni reflects on the unique sense of Chinese horror, and why its stories remain under-explored.

When I put the words, “Chinese” and “Horror” together, what do you think of? Those long robed and confusingly named hopping vampires? 18th century tales of beautiful female ghosts? Or the latest tirade in the popular press regarding China’s alleged nefarious intentions? Chinese horror as a subgenre of literature is very much underexplored, and as a collector of contemporary strange tales, and a writer of China’s cultures, I am on a mission to encourage the reading, enjoyment and development of this fascinating regional genre. One of the first conditions, where I must ask readers to do some work, is to set aside your preconceptions about the nature of horror fiction, and consider, what is the Chinese Sense of Horror?

Classically, the supernatural are not intrinsically associated with fear in China. Ghosts, spirits, and even the Mo(commonly known as ‘‘demonsâ€) are seen as a natural part of an order in which mortality is just one form of existence. Souls pass to the nether world after death and return to the living, either as a different person, or in another form. Spirits are traditionally believed to be all around us, making their own way through the eternal cycles of the Dao, existing in plants, animals, and even old objects can develop them. It’s only when humanity has exceeded its reach, or when a life has been prematurely ended, or not been laid to rest properly, that the supernatural become a threat to the mortal realm.

This does of course lead to a very different set of attitudes and taboos around things like death, and how the departed are treated. An English person may not think twice about keeping Nanna Sibyl’s ashes on the mantelpiece and may even feel it homely to have her still, if not pottering around the place, at least potted. This would, however, feel creepy as hell to a Chinese person. Of course, they want their dear departed to be happy and have everything she desires in the next world. They would purchase a nice plot of land for nainai, sweep her tomb, make regular offerings on the ancestral altar, but they don’t want her back with them, and keeping her ashes around the house would be a surefire invitation for a grumpy granny ghost, upset that they hadn’t helped her move on to the next cycle of life.

There are times when the channels are open between the two realms, such during Zhongyuan, a Chinese festival similar to Mexico’s Dias de Les Muertos, when they’d welcome nainai’s visit with feasts, but precautions must be taken. In other words, these two spaces that are culturally separate and therefore physically set apart. When forbidden boundaries are crossed, with a contamination the space of the living by the energy of the dead, or when a ghost makes their presence known to the living, then something is wrong, and this is when Horror begins.

There is, of course, the Chinese belief in retribution, a concept that extends far beyond the influences of Buddhist karma, with the idea of baoying being so ingrained in the popular consciousness that it is not unusual to see the most morally depraved of villains crumple when confronted with the vengeful ghost of their victims. It’s such a deeply held sense of justice that even as modern books replace the mystic with the psychological, there exists a yearning for this return to balance. This is one reason why social horror has been a natural direction for Chinese literature, ever since the role of fear and dread in the revolutionary tales of early cinema in the 1930s. As China’s society tries to catch up with the country’s rapid economic changes, there’s plenty of material fuelling this rising sub-genre.

(Photo by 烧ä¸é…¥åœ¨ä¸Šæµ· è€çš„ on Unsplash)

When I began lecturing on China’s horror storytelling, I found myself constructing it from the margins of academia, blog commentaries and reconsiderations of familiar sources. While Horror has existed as an element in the traditional zhiguai(tales of the strange), those records had started as a way of cataloguing China’s strange lands and peoples, during times of territorial expansion. In time, the duller elements, such as preferred crops of each region, and local building techniques, were eventually removed, the hyperbolic, and sometimes just straight up fictional recounting of giants, dragons, man-eating fish people and doom bringing birds, have survived, presented as eye-witness accounts, in as matter of fact a fashion as possible. And books like the “Guideways Through Mountains and Seas†are now considered as literary classics.

As a nation with diverse environs, peoples and beliefs, the Chinese sense of horror is distinctly regional, with the more mountainous regions acting like a breeding ground for horror writing, whether those are the imposing ranges of east and central China, the gothic spire-like mountains of the south, or the densely wooded, unfathomable mountains of the west. These regions each have their histories of myths and monsters, but the isolation, danger, and unique threats of each area continue to inform new writing. That may lead you to feel that Chinese Horror is a purely rural thing, and so much of what we’ve seen in the West has been, but as China’s landscapes become increasingly more urban, so does its horror fiction. From derelict building sites, to isolated peripheral suburbs, to the slums squeezed between futuristic high rises, there’s a new fear of abandonment, being left behind, or eaten up in the path of progress. The liminal spaces created by China’s rapid growth have become the modern equivalent of desolate graveyards, ruined temples and deserted villages, where the creepiness seeps out of the glamorous veneer of metropolitan life.

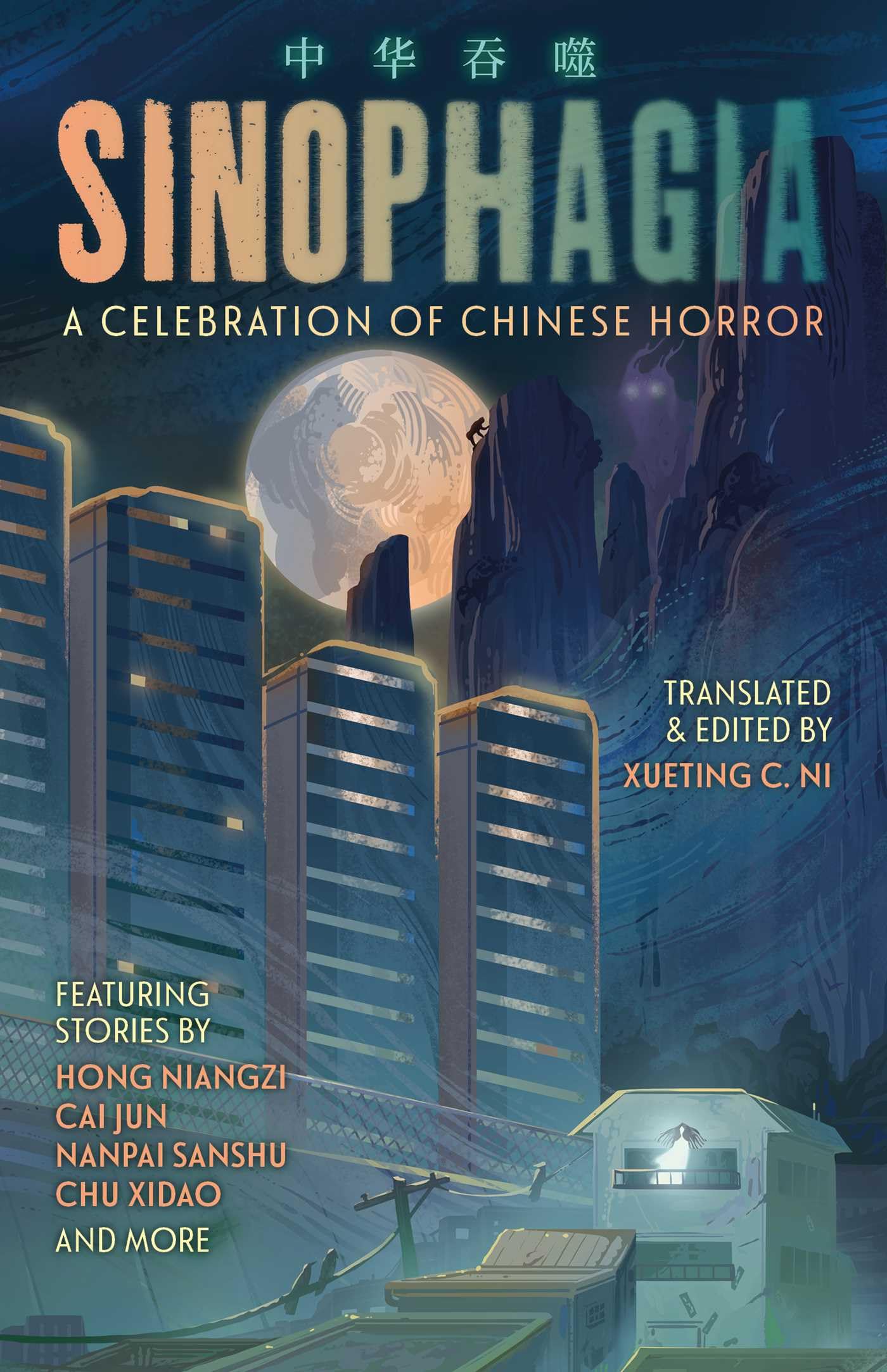

China’s current attitude to Horror is a peculiar one. The mini explosion of horror writing in the late 90s to early 2000s led to a moral uproar, with allegations of copycat killings and incitement to violence being laid firmly at the doors of an industry that was increasingly employing gratuitous gore and cheap thrills. The term “kongbu†became a negative, in fact, because of the way Chinese words are incredibly contextual; if you search the term these days, you’ll find it mostly applying schlock horror. This made researching and reaching out for my collection of Chinese horror, Sinophagia, problematic, to say the least. Very few writers and illustrators wanted to consider their work kongbu, or even the mildly less negative term jingsong, preferring to call it xuanyi, meaning “thriller†or “suspenseâ€, all to escape those connotations. It’s why I’ve begun to use the term Kongxuan, to separate the well-written horror from the schlocky cash grabs that attempted to exploit the profitability of the genre in the past.

This is not the first time I’ve found myself fighting uphill to support a genre so looked down on. When I first started pitching my previous collection Sinopticon, focused on Chinese science fiction, the domestic view of SF was poor to say the least. Searching for possible authors on the shelves of Xinhua bookstores, clerks would sigh and point me to the children’s section, or Science Education. The talent that I saw burgeoning in magazines and online repositories showed me that there was going to be an explosion in the genre, and it was that same electrical energy that made me feel the time was right to bring Chinese horror literature back to the world with Sinophagia.Â

Whilst I’ve argued here for the relearning of horror, the understanding of China’s traditional relationships with the supernatural and its new discomfort with wealth and progress, I believe that beyond the exercise in cultural understanding, the actual emotions of horror transcend boundaries. This genre is a literature that unites rather than divides. Yes, there are very specific things that carry a sense of fear or discomfort in China, but the way the body reacts to a trigger is universal. It’s silly to get tingles at a number, but there are people in the West who’ll avoid the number 13, in the same way that someone in China may avoid the 4th flat on the 4th floor.Â

Even deep dives into the genre will find that the tropes of the Victorian Gothic have their equivalences in Chinese storytelling, and though the trappings and narrative rules might vary, the Chinese Gothic will still feel familiar. Fear of the unknown is a common perspective across nations, as is the sensation of the uncanny, or unheimlich. The conversation between the China’s own and other traditions is already well underway, and decades of absorbing foreign ideas, arts and entertainment have meant that Chinese writers, as well as readers, are somewhat attuned to globalised tastes, and whilst the actual moments that invoke fear may feel unusual, the descriptions of cold sweats, prickling hair, and rising dread will feel all too familiar.

All horror writers and readers share the desire to confront and comprehend the dark veracity of the human experience, and I hope that new collections, like Sinophagia, will encourage you to explore the genre beyond the culture, and delve into not only Chinese horror, but other Asian, and World writers as they bring fear to the page.