In this latest edition of her regular column, Tiffani Angus—co-author of Spec Fic for Newbies volumes 1 & 2—warns us not to go there, especially not there.

From toddlerhood, most of us just couldn’t help ourselves. When our parents or another adult said, “No,” we did it anyway. Don’t touch the stove … cue screaming. Don’t pull the dog’s tail … cue crying. Don’t go on those stairs … cue falling plus crying plus screaming. Some of those toddlers grew up to sneak a peek into an abandoned building, ski down black-diamond slopes, or even just jump on the back of the shopping trolly and ride it through the carpark. We all have our own approaches to adventure, but some stories take us into the dark heart of places we really shouldn’t go.

And that’s where adventure trips over into horror: when a bit of fun becomes a giant nope.Â

Our world is filled with dangerous places, and we humans have spent centuries—millennia—trying to figure out how to go there. But should we? The warning mixed with the truth of those places takes us into the realm of horror, and this month, the Subgenre Trope Deep Dive is unfolding the map to explore Places People Shouldn’t Go.Â

This is a condensed and tweaked version of the same section from Spec Fic for Newbies Vol. 2: A Beginner’s Guide to Writing More Subgenres of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror (2024) by me and Val Nolan, out from Luna Press. Both volumes 1 (2023) and 2 were included on Locus’s Recommended Reading List and were finalists for the BSFA Best (Long) Nonfiction award.Â

Volume 1 also made the BFS Best Nonfiction shortlist and was *thisclose* to the Hugo shortlist. Each book contains thirty subgenres and tropes from Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror, their histories, identifying elements, lists of what’s cool and pitfalls to avoid, and activities to get you writing. Plus the usual puns and snarky jokes! So, what are you waiting for? See https://linktr.ee/specficfornewbies for purchasing links. Oh, and keep your eyes peeled for a third volume to drop Easter 2026!

This month is a look at… PLACES PEOPLE SHOULDN’T GO!

The notion of Places People Shouldn’t Go (PPSG) is something that’s culturally determined, deriving from an ever-changing mixture of social and technological influences. On a basic level, there are places you shouldn’t or can’t go because you’ll die or get hurt (Chernobyl) or because of financial or technical limitations (the Outer Solar System); there are places you’re not allowed to enter for legal reasons (Area 51); and then there places you’re discouraged from going by peer groups, usually because of socio-economic inequality, racism, or a general fear of difference (“bad†parts of town, etc). All provide compelling backdrops for writers to deploy horror tropes on account of the built-in unease—or worse, in the case of the particularly deadly examples—that they generate in our protagonists. This is true even when characters deliberately seek out these locations because then hubris can be used to great effect (“Other people have died here, but I’ll be okayâ€). Remember the modern adage that every frozen corpse on Mt Everest was once a highly motivated person!

Back in the day, of course, people didn’t go very far from their home tribe or village, partially because strangers were regarded with distrust and subject to violence, and partially because it took forever to get anywhere before planes, trains, and automobiles. Not that this stopped the hardiest—or foolhardiest—human specimens who wanted to see the world. Even today, some people go places that they shouldn’t just for the hell of it, for the bragging rights of glimpsing the wreck of the Titanic through a tiny porthole or seeing the curve of the planet from a billionaire’s vanity spacecraft.

Of course, the original bragging rights came in the form of tall tales and half-truths about what was “out thereâ€: Vikings who struck out to the west and never returned (though archaeological evidence tells us they reached Greenland and North America); Marco Polo’s adventures in the East (recorded in The Travels of Marco Polo, c. 1300); Arab adventurer Ibn Battuta’s travels across 100,000+ km of Africa, Asia, and Europe in the mid-1300s (more than any other explorer in pre-modern times); Chinese admiral Zheng He’s expeditionary treasure voyages; and many more. Yet to trust in the veracity of second-, third-, or fourth-hand travellers’ yarns was to take your life into your own hands.

The idea of the factual guidebook, in the modern sense, came later. One of the earliest examples is Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam (A pilgrimage to the Holy Land; 1486), depicting a trip undertaken by Bernhard von Breydenbach in 1483–’84. In the following years, economic factors and advances in technology pushed European nations (in particular) ahead of their Asian and Arabic counterparts. Most (in)famously, Christopher Columbus sailed across the vast uncharted western ocean in search of a quicker passage to the rich lands of the Far East but “discovered†the Americas instead. The result was a bloody and genocidal age of colonialism and enslavement—the effects of which are still felt today on both sides of the Atlantic—with the Columbus expeditions emboldening countless European explorers, traders, and violent conquerors (oftentimes all three in one) to fan out across the world to places they shouldn’t go.

Among them were Amerigo Vespucci (from whom we get the name “Americaâ€), Francis Drake, Henry Hudson, Hernando Cortez, Ferdinand Magellan, James Cook, and many others. Such explorations typically had a military or extractive character, often sponsored by governments eager for resources and various trading goods, such as with the Dutch East India Company. A great take on conquerors vs the home team is ‘Jibaro’ (dir. Alberto Mielgo, 2022), an episode of the third series of Netflix’s Love, Death & Robots, about a Spanish conquistador’s encounter with a siren. And no, it’s not gen AI!Â

Further, higher, deeper

This Age of Discovery—though one imagines that terminology coming as quite a surprise to the millions of people “discoveredâ€â€”filled in many blank spaces on European maps of the world. This in turn inaugurated a race to reach the farthest, highest, or deepest points, the very definitions of PPSG. Enter the explorers and scientists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many of whom targeted places that weren’t necessarily even habitable. These expeditions got underway in the late 1800s when “international scientific consolidation took place†because these sorts of projects were “expensive, highly organised and often took place on a co-operative international basisâ€. Such voyages included that of marine biologist Charles Wyville Thomson to study the deep sea aboard the Challenger (1872–’76), though nobody from that ship dove deep underwater, and British officer Robert Falcon Scott’s South Pole explorations aboard the Discovery (1901–’04) and the Terra Nova (1910–’12), during which Scott and three of his crew died.

Since then, people have reached the poles, scaled the highest mountains, dived to the bottom of the ocean, and fought the elements in deserts, caves, and other unfriendly PPSG. They even explored closer to home, in abandoned buildings, tunnels, and high rooftops, not to mention the selfie hunters who hang off radio towers for social media likes. But why? (No, really, why hang one-handed off a ridiculously tall building for the internet?) One reason might be hardwired into our brains. First of all, there’s dopamine, “often described as the brain’s ‘pleasure chemical’â€; any rewarding experience can trigger the dopamine system, and it seems that “an active dopamine system can make us take more risksâ€.Furthermore, research has discovered that “people with a certain dopamine receptor are more likely to be thrill seekingâ€.

(Photo by Buddy Photo on Unsplash)

So, taking a risk will give you a dopamine hit, which feels nice, which then sends you searching out another dopamine hit. The term “adrenaline junkie†makes more sense now!

Naturally, not all dopamine receptors are built the same, and some people seek bigger thrills than most of the population; additionally, research shows that people with “greater brain activity in the striatum, a region involved in dopamine releaseâ€Â may make more risky choices because “the novelty increases dopamine release in this area of the brain, which then possibly enhances the expectation of rewardâ€. This suggests that the people who climb the highest mountains, dive the deepest oceans, and go to Places People Shouldn’t Go are built a bit differently from most of us.Â

Overriding the survival instinct

Thrill-seeking has long inspired writers, providing an opportunity to create characters who’ll stop at nothing to push their limits. Dr Kenneth Kamler, an orthopaedic microsurgeon who’s practiced medicine in some of the most remote and dangerous places on the planet, puts it plainly: “No animal in its right mind ever intentionally puts itself in danger by going somewhere it doesn’t belong. Human beings, on the other hand, are controlled by brains whose emotional and spiritual imperatives can override the survival instinctâ€. So, while some of us are out there putting our very bodies on the line, the rest of us can get that sweet dopamine hit by reading about the adventures or watching them unfold on visual media.

Planet Earth has supplied many suitable environments for horror settings, with or without supernatural or fantastical additions:

- Pole to pole: The North and South Poles are places of extreme temperatures, winds, and isolation, with myriad dangers such as storms, crevasses, frostbite, a distinct lack of fuel or food, and polar bears (though only at the North Pole; and yes, they are that bloody big). After the poles were conquered, novelists started to insert more horror elements into their tales. H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic-horror novella At the Mountains of Madness (1936) follows an Antarctic expedition that encounters the remains of an ancient civilisation built by shoggoths that laboured for the “Elder Thingsâ€. In John W. Campbell’s seminal body-horror tale Who Goes There? (1938), the crew on an Antarctic research base thaws out an alien’s body, which begins to shapeshift and imitate them; it’s been filmed several times, the most famous being John Carpenter’s 1982 adaptation The Thing.

- Mountain air: Some people love the challenge of thin air, high altitude, and exposure. All these elements, plus a supernatural creature or two, make for an exciting tale. “Found footage†films ramp up the inherent horror; for example, Devil’s Pass (dir. Renny Harlin, 2013) combines the dangers of climbing with a mysterious bunker and creepy creatures. Echo (2022) by Thomas Olde Heuvelt tells the story of a climber whose accident on the peak of a forbidden mountain has ruined his face to the point where other people go mad just by looking at him.

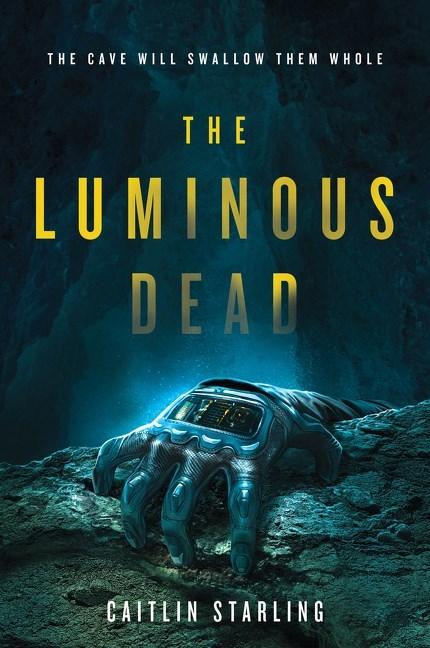

- Cue the claustrophobia: Stories about spelunking in caves don’t necessarily need supernatural-horror elements to be horrifying for some people; claustrophobia can do that all by itself, thank you very much! Plus, we don’t need fiction to scare us when we have the true story of a man who got stuck upside down while spelunking, died in the tiny crawl space, and was entombed there in 2009! The Anomaly (2018) by Michael Rutger features a crew exploring and getting trapped in a cave in the Grand Canyon where things aren’t exactly normal. And horror and science fiction overlap in The Luminous Dead (2019) by Caitlin Starling, set on another planet with tech—such as a protection-suit/wetsuit that can be controlled from the surface—and a cave that, as usual, houses a secret.Â

- But it’s a dry heat: Horror set in the desert isn’t always related to the environment, as proven by the classic The Hills Have Eyes (dir. Wes Craven, 1977), complete with a cannibalistic family preying on anyone who accidentally crashes in the Nevada desert. Josh Malerman’s Black Mad Wheel (2017) follows a band hired by the military to track down a malevolent sound emanating from the Namib desert in Africa. Here, too, filmmakers have taken advantage of the popularity of “found footageâ€: Horror in the High Desert (dir. Dutch Marich, 2021) is a mockumentary about a hiker missing in Nevada’s Great Basin Desert whose left-behind footage shows a mysterious cabin and a deformed human-like figure.Â

- In too deep: Aquatic horror often manifests as man vs fish, but the horror is ramped up when characters must deal with scuba gear (sketchy regulator?), the depth (pressure and the danger of getting the bends when surfacing too quickly), and support systems (or lack thereof when the boat leaves without them!). In Open Water (dir. Chris Kentis, 2003), a diving couple are stranded off the Great Barrier Reef when their boat abandons them; while nothing supernatural happens in the film, it’s terrifying because it’s based on a true story, with the movie speculating what might have happened. Are there sharks? Of course there are sharks, something covered in another Deep Dive about Animals That Attack! In They Came from The Ocean by Boris Bacic (2022), the author sends his characters to an unforgiving 11,000 feet underwater and, just for funsies, adds in something stalking the stranded crew.

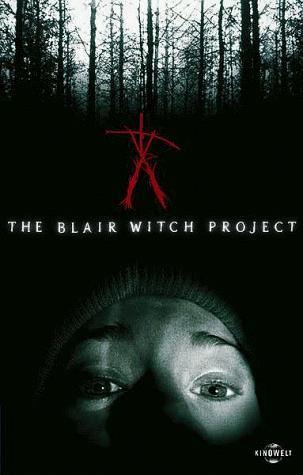

- Follow the breadcrumbs: We all enjoy a hike, don’t we? The smell of fresh trees, the clean air and sunshine, a random serial killer or two, and nobody to hear you scream. The Blair Witch Project (dirs. Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, 1999)—the most famous “found footage†horror film—follows a trio of students who venture into the Maryland wilderness to uncover a local legend; they get lost but find a historical killer’s home and then go into the basement (definitely a place people in horror films shouldn’t go!). Meanwhile, in Adam Neville’s The Ritual (2011), a group of four friends dealing with their own dramas really should have stayed out of the Scandinavian backwoods, with its pagan sacrifices and violent black metal band mates.Â

So, we’ve learned that some people in the past didn’t feel alive unless they were pushing the envelope (before there were envelopes) and finding where every road ended; some people who now live in a time when every inch of the globe has been mapped do what they can to feel alive and suck up that sweet, sweet dopamine; and some of us are very happy to stay home but scare ourselves thinking about what’s over the horizon.

It makes sense that this trope has made “found footage†films so popular: viewers can “be there†with the people pushing themselves to the limit whether it’s underground, high in the mountains, or off the hiking trail. We don’t have to empty our bank accounts or put ourselves in harm’s way to experience Places People Shouldn’t Go.

Some more suggested reading (not included in the article)

- Sarah Lotz’s The White Road (2017; caves and mountain climbing)

- Algernon Blackwood’s ‘The Willows’ (1907; wilderness)

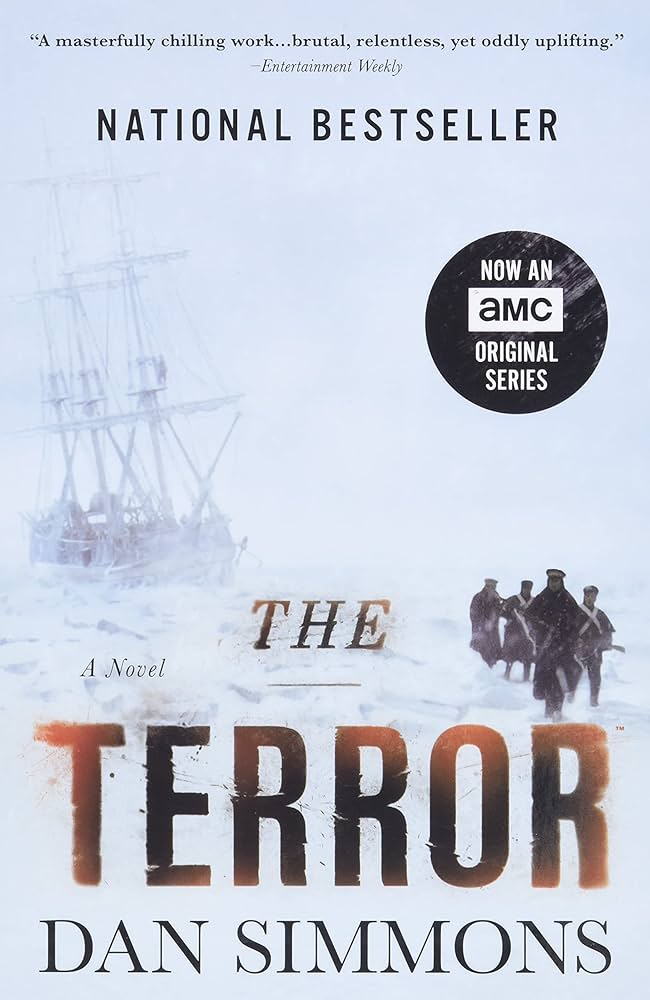

- Dan Simmons’s The Terror (2007; about an 1840s polar expedition)

- Mira Grant’s Rolling in the Deep (2015; ocean)

- Vaughn C. Hardacker’s Wendigo (2017; wilderness)