We’ve implemented some new protocols around sending us messages via this website. Please email website “at” britishfantasysociety “dot” org for any issues.

For all things fantasy, horror, and speculative fiction

-

Announcement:

Subgenre deep dive: Animals That Attack

In this latest edition of her regular column, Tiffani Angus—co-author of Spec Fic for Newbies (including the soon-to-be-released Volume 2!)—looks at that most summer blockbustery of tropes: the creature that turns on humanity.

Ah, summer. That time of year when kids are buzzing to get out of school and explore, when parents and other adults gear up for holidays abroad—or close to home—backyard picnics, and just being outside without a coat, gloves, and hat, or the ever-present (and necessary lately if you live in the UK) umbrella. We spend so much of our lives indoors that, when it’s finally sunny and warm, we just want to go outside. You know, that place with grass and birds … and bugs … and snakes … and rabid dogs … and bears out of hibernation … and squirrels with a bad attitude.

This month, the Subgenre Deep Dive is taking you on a little side trip into a popular trope in horror: animals that attack. This one is a sneak peek into the Spec Fic for Newbies series’ new volume: Spec Fic for Newbies Vol. 2: A Beginner’s Guide to Writing More Subgenres of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror out 2 July from Luna Press!

Spec Fic for Newbies Volume 1 (2023) was recently featured on Locus’s Recommended Reading List and made the BSFA Best (Long) Nonfiction finalist list, so why not see what Volume 2 has in store. You’ll find thirty more subgenres and tropes from Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror, their histories, identifying elements, lists of what’s cool and pitfalls to avoid, and activities to get you writing. Plus the usual puns and snarky jokes! So, what are you waiting for? Pre-ordering links are here.

This month is a look at… ANIMALS THAT ATTACK

Humans have always lived alongside animals. Some were domesticated early, others were food, but for others we were the food. Animal attacks made it to early historic records, such as in Carmarthen, Wales in 1166, when wolves attacked 22 people, as well as other wolf attacks in Evreux in 1400 and Rouen in 1445. It wasn’t long before our stories also fictionalised animal attacks. Some of the most amusing are the “killer bunnies” found in the margins of mediaeval-era illuminated manuscripts. These rabbits don’t attack with fangs bared, à la the rabbit in Monty Python and the Holy Grail(dirs. Terry Gilliam and Terry Jones, 1975), but use swords and arrows against human hunters, showing the rabbits and hounds in a topsy-turvy world “where roles are reversed and the impossible becomes the norm”. This idea—of animals attacking humans who are armed and, supposedly, the top of the food chain—developed into a popular trope in horror fiction.

Our encounters with animals now run the gamut from having a cat purring on our laptops while we try to work, feeding pigeons in the park, paying to see wild animals in the zoo, and avoiding bears and bison at Yellowstone (or, thinning out the gene pool by trying to take selfies with them. Please don’t.). In modern horror, we can look back about a hundred years to a solid start of the trope with Henry Kuttner’s ‘The Graveyard Rats’ (1936) in which a cemetery caretaker/grave robber in Salem, Massachusetts, fights off—you guessed it!—giant rodents. The tale later made into an episode of Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities (dir. Vincenzo Natali, 2022).

One of the most popular early instances, however, is Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1953), based on Daphne du Maurier’s 1952 short story. While the short story is about gigantic flocks of avian antagonists attacking people across Britain, the film moves the flocks to California. It wasn’t just the du Maurier story that got Hitchcock thinking about horror with wings; he was also inspired by an event in 1961 in California during which sea birds “regurgitated anchovies, flew into objects and died on the streets” because of eating toxic algae, although that reason wasn’t discovered until a similar event thirty years later. Truth is stranger than fiction, indeed!

Image: Still from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1953), from Mubi (source)

Technology + environmental concerns + nuclear waste = bad

The real impetus for the evolution of this trope can be found in the middle of the twentieth century with the development of new technology (used at home and in wars abroad), the subsequent growth of environmental concerns, and, strangely, the popularity of men’s adventure magazines. In the 1950s and ’60s, the “atomic age” led to fears of what science was doing to the natural world. One of the first films to exploit this fear is 1954’s Them! (dir. Gordon Douglas), featuring man-eating ants that have grown to the size of military tanks as the result of being irradiated despite the fact that, scientifically, an ant that size wouldn’t be possible because their legs would collapse under their weight (but, hey, who lets science get in the way of fantastical films?).

From there we can chart the rise of environmental groups working to save the planet, many as an offshoot of the hippie movement of the 1960s and ’70s, such as Friends of the Earth (1969) and Greenpeace (1971). The US government also turned its attention to the environment around this time by passing the Clean Air Act (1963) and the Clean Water Act (1972), as well as establishing the independent Environmental Protection Agency (1970). People were concerned about nuclear waste, acid rain, pollution, littering, pesticides, and more; consequently, the fact that so many animal-attack novels and films were created in the 1970s isn’t a surprise.

(Photo by Nikolas Gannon on Unsplash)

Coinciding with all this was a rise in the popularity of men’s magazines that featured stories revisiting the “pulp” mode of previous decades, among them Man’s Life magazine, which ran from 1952 to 1975. Its full-colour cover illustrations would show humans (usually manly men and sometimes scantily clad women) being attacked by the expected bears, tigers, and lions, but also by unexpected hordes of flying squirrels, weasels, and snapping turtles! A wrinkle to the growth of the animal-attack trope is the combination of environmental concerns, weapon development, and men’s lives post-war in stories in which the men take part in military or government experiments on animals to turn them into weapons, with the expected angry-animal results.

In horror fiction from the 1970s and 1980s, these animals that attack because of human interference come from various ecosystems. On land we have Rats (1974) by James Herbert, arguably the start of the popularity of this trope in the past fifty years, which features giant rats that—you guessed it—have become mutants due to nuclear waste; they run rampant all over London and then into the English countryside in the sequel Lair (1979), but return to a now post-Apocalyptic London in the trilogy finale Domain (1984). In Nick Sharman’s The Cats (1977), lab animals used in bacterial-weapon tests get loose, and you can guess what happens next.

In 1978, the trope straps on a snorkel in the film Piranha (dir. Joe Dante) when flesh-eating swarms of genetically altered fish (part of a defunct experiment to create killer fish during the Vietnam War) terrorise tourists in a riverside summer resort. The trope continues in Peter Tonkin’s novel Killer (1979) about an orca, again, attacking a group of people. And in Fleshbait by David Holman and Larry Pryce (1979), nuclear waste has leaked into the sea and turned schools of fish, including tuna, into killers. These human-affected animals also crawl, as in The Spiders (1978) by Richard Lewis, which features a horde of genetically altered spiders (created to be a weapon, of course!) out for blood, and the spiders return for more in his sequel The Web (1981).

Sharks just being sharks?

But what about animals that are just, well, being animals? They’re still attacking on the page and the screen, and anyone who blocks off the annual summer feature Shark Week on the Discovery channel can tell you that audiences can’t get enough. In these animals-that-attack stories, we still sometimes see outlandishly sized animals, but the nuclear-waste reasoning isn’t always as evident. Instead, humans often invade the animals’ environment for money or sport, or they retaliate against the animals for just doing what animals do. All of which is to say that, in the end, it isn’t so much natural behaviour that’s the catalyst for animal attacks: it’s human behaviour itself.

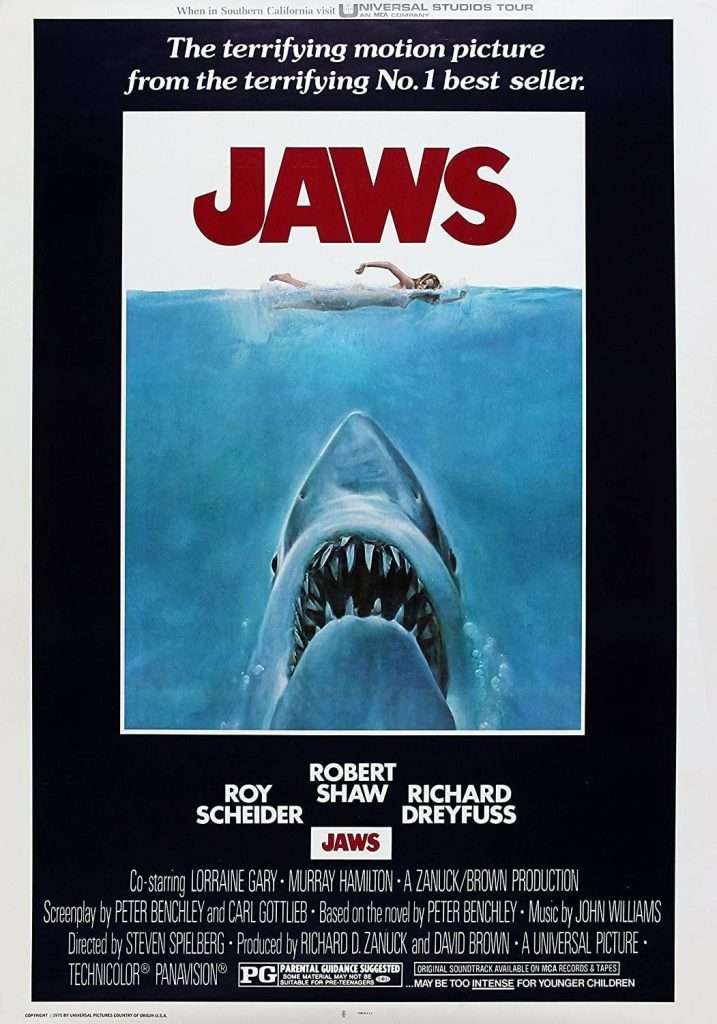

Sharing the limelight with Rats as the granddaddy of this trope is, without a doubt, Jaws (dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975), based on Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel of the same name. Unfortunately, its sequels never live up to the greatness of the original but make for a fun night of MST3K-esque quips because of the lack of anyone ever knowing or even questioning anything at all about actual shark behaviour (because what would be the fun in that?). In The Pack (1976) by David Fisher, attention turns to man’s best friends with a tale about dogs abandoned on a vacation island that join forces to get revenge on humanity. A bit later, horror fans were scared by another massive denizen of the deep in Orca (1977) by Arthur Herzog, later filmed as Orca: The Killer Whale (dir. Michael Anderson, 1977), about a man hunting an orca that’s out for revenge because the man killed the fish’s mate and offspring, which possibly foreshadowed the current orcas vs yachts throwdowns happening in various places. Although we all do what we can now to save the bees, they weren’t cute, fuzzy-bottomed lifesavers in Herzog’s The Swarm (1978), in which “Africanised” bees (yes, the term carries racist tones) are turned into killers and bring on America’s downfall. And the well-known Cujo (1981) by Stephen King pits a rabies-infected St Bernard against a mom and her young son trapped in their broken-down car, with the book’s ending much darker than the film adaptation (dir. Lewis Teague, 1983).

While the trope mostly hibernated for a while, it’s come back with a vengeance in the past decade, most notably with sharks and other water-borne animals (possibly revenge for the Great Pacific Garbage Patch?). In The Meg (dir. Jon Turteltaub, 2018), loosely based on the novel Meg: A Novel of Deep Terror (1997) by Steve Altenin, Jason Statham goes mano-a-fin-o with a 75-foot long megalodon, a prehistoric species that’s been hiding in a very deep section of the Marianas Trench. A quick search on your streaming platform of choice will bring up no end of bad shark films, but one to catch is Shark Bait (dir. James Nunn, 2022), in which five college kids are marooned far from shore on two broken-down jets skis and picked off, one by one, by an angry shark. Meanwhile, in 2019’s Crawl (dir. Alexandre Aja), an alligator traps a daughter and father in a flooding house during a hurricane, a warning of what could happen as these storms become stronger and more prevalent as a result of climate change.

When the attack goes bizarre

Then there are those animals-that-attack tales that are just completely bananas. Of special interest is the ridiculous but fun Sharknado (dir. Anthony C. Ferrante, 2013) and its five sequels.

Say “snake” and the infamous film Snakes on a Plane(dir. David R. Ellis, 2006; and written by, it feels like, the Internet) is probably the snake-attack story that most readily comes to mind: terror ensues when a box of snakes is stowed aboard a plane and the passengers sprayed with a substance that makes the snakes want to attack them in this bonkers-level Samuel L. Jackson vehicle. Finally, one of the most outlandish and funny-gory bear-attack narratives based partially on fact (yes!) has to be Cocaine Bear (dir. Elizabeth Banks, 2023) in which a bear goes all Scarface in a Georgia forest after huffing its way through parcels of cocaine dumped out of a smuggler’s aircraft.

Image: still from Snakes on a Plane (source)

These stories still depict animals acting like animals, but the attacks are definitely our fault (well, maybe not in the case of Sharknado!).

Ultimately, animals-that-attack tales, though thrilling, are about our relationship with our environment, especially in our current Anthropocene hellscape. Some of us find the great outdoors a scary place, while others see it as a resource to be used. But in all cases, these tales are about the environment—in all its furry, scaly, feathered glory—fighting back, and that’s where the horror lies: human flesh is no protection against claws and teeth and pure animal instinct, especially when we find ourselves in their neighbourhood.

Some recommended reading/viewing

(including entries not found in the article)

- Henry Kuttner’s ‘The Graveyard Rats’ (1936)

- Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds (1953), based on Daphne du Maurier’s ‘The Birds’ (1952)

- Them! (dir. Gordon Douglas, 1954)

- James Herbert’s Rats (1974), Lair (1979), and Domain (1984).

- Peter Benchley’s Jaws (1974) and Steven Spielberg’s film Jaws (1975)

- David Fisher’s The Pack (1976)

- Tentacles (dir. Ovidio G. Assonitis, 1977)

- Nick Sharman’s The Cats (1977)

- Arthur Herzog’s Orca (1977) and Michael Anderson’s film Orca: The Killer Whale (1977)

- Guy N. Smith’s Night of the Crabs (1976) and its sequels up to The Charnel Caves: A Crabs Novel (2019).

- Piranha (dir. Joe Dante, 1978)

- Arthur Herzog’s The Swarm (1978)

- Barracuda (dirs. Harry Kerwin and Wayne Crawford, 1978)

- Richard Lewis’s The Spiders (1978) and The Web (1981)

- Peter Tonkin’s Killer (1979)

- Peter Tremayne’s The Ants (1980)

- Stephen King’s Cujo (1981), and Lewis Teague’s film Cujo (1983)

- The Ghost and the Darkness (dir. Stephen Hopkins, 1996)

- Anaconda (dir. Luis Llosa, 1997)

- Steve Alten’s Meg: A Novel of Deep Terror (1997) and Jon Turteltaub’s film The Meg (2018)

- Legion of Fire: Fire Ants (dirs. Jim Charleston and George Manasse, 1998)

- Snakes on a Plane (dir. David R. Ellis, 2006)

- The Grey (dir. Joe Carnahan, 2011), based on Ian MacKenzie Jeffers’s ‘Ghost Walker’

- Sharknado (dir. Anthony C. Ferrante, 2013) and its five sequels

- Crawl (dir. Alexandre Aja, 2019)

- Shark Bait (dir. James Nunn, 2022)

- Cocaine Bear (dir. Elizabeth Banks, 2023)

Meet the guest poster

Explore the blog:

Blog categories:

Latest Posts:

Tags:

#featured (56) #science fiction (25) Book Review (264) events (44) Fantasy (231) Graphic Novel (13) horror (136) Members (62) Orbit Books (48) profile (43) Romance (17) Science Fiction (50) short stories (28) Titan Books (52) TV Review (15)

All reviews

Latest Reviews:

- THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND by William Hope Hodgson

- Monstrum by Lottie Mills

- Mood Swings by Dave Jeffery

- Yoke of Stars by R.B. Lemberg

- Hera by Jennifer Saint

- The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness

- RETURN OF THE DWARVES By Markus Heitz

- Delicious in Dungeon

- Toxxic by Jane Hennigan

- THIS ISLAND EARTH: 8 FEATURES FROM THE DRIVE-IN By Dale Bailey

Review tags:

#featured (2) Action (4) Adventure (4) Book Review (28) Fantasy (18) Featured (2) Feminist (2) Gothic Horror (3) Horror (14) Magic (3) Orbit Books (3) Romance (6) Science Fiction (5) Swords and Sorcery (2) Titan Books (7)