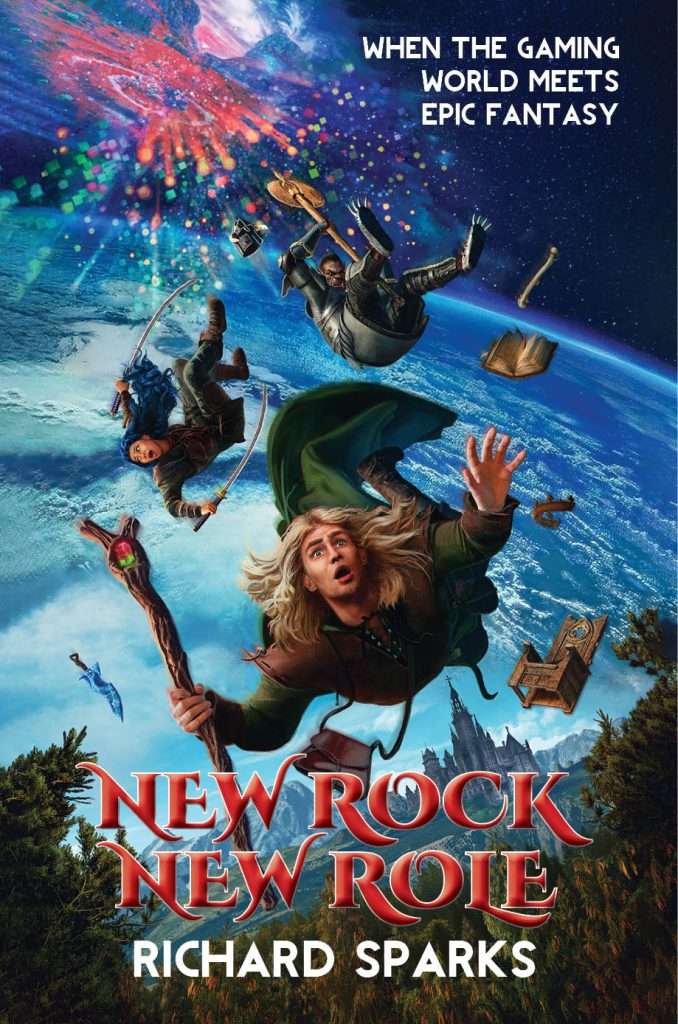

He’s worked with some of the biggest names in comedy, film and music, and now Richard Sparks has turned his talents to writing fantasy fiction inspired by his love of gaming. Here, he reflects on how these worlds are perfect companions.

My old friend Douglas Adams was into video gaming long before I was. But then, Douglas was always ahead of his time. We’d known each other since our student days (at different universities), meeting in Edinburgh with our comedy revues. We had the same London agent (Jill Foster) and many friends in common. We were also both huge fans of Robert Sheckley, loving his blending of comedy with SF&F.

Comedy isn’t nice people telling jokes. That’s a dinner party. Comedy is about things going wrong; about fear, and pain, and suffering, and misunderstanding, and confusion, and disaster, and falling into puddles and running for your life from monsters. And what good adventure isn’t filled with those?

And in a role-playing game, it really is your life. You’re not passively watching an actor up on screen. You’re the hero of your own adventure. You design your avatar to look how you want them to look. You equip them with the skills you want them to have, and off you go into a new and unknown world, to see what challenges and puzzles—and rewards—await you.

Those worlds—ones that designers and developers have created for us to enjoy and experience—are astonishing. Some can be realistic, but only up to a point. Most are as wild and wonderful as the worlds that we love in speculative fiction—and you’re right in the middle of them. They’re all around you. Yes, there are quests, and puzzles, and storylines, but you can ignore those and just go exploring, taking in the scenery. I’ve adventured in yakuza Japan and deep space, in ancient histories and steampunk Victorian alt-Britain and horror-filled dungeons. My favourites, though, are the sword-and-sorcery worlds.

It was while running on a PvP (Player versus Player) raid with a group of fellow mischief-makers in one such world that the idea for New Rock New Role fell out of the sky and hit me on the head like an anvil onto Wile E. Coyote. What would it really be like? To be that guy? That heroic, young battlemage, with his magic staff, in a fantastical world like that? For real?

There was only one way to find out.

Write it.

And that’s where the comedy came in soon enough. Because, of course, if you really found yourself as your own avatar, in a real world (not in a game), you’d be completely useless. You may be skilled at mashing a keyboard, or a console—I don’t know about you, but I’ve never held a real sword in my life. So there I was, in a wilderness I’d never seen before, armed only with noob-level gear, and there’s no sign of my two team-mates…

And I’m being hunted by wolves.

It can, of course, only get worse.

Mining the same fertile soil

Fantasy takes us to places where realism doesn’t attempt to go. We love it because it beckons us towards new horizons beyond the constraints of our everyday, humdrum lives. What if. What if we weren’t bound by what we know, and see around us every same-old day, but instead got the chance to venture into the great unknown?

Fantasy and gaming are natural partners. They mine the same fertile soil. That soil is the legacy of our cultures, handed down to us over the ages. The Epic of Gilgamesh; The Ramayana; The 1001 Nights; the classics of East Asian lands; the oral traditions of Africa and the Americas; European folklore and traditional tales, such as those collected by the Grimm Brothers—what Marina Warner terms “wonder tales”—all are fantasies.

The circle of music and fantasy and gaming becomes complete when we give games the respect they deserve

Richard Sparks

The first great literary work in the English language is a fantasy epic: Beowulf. It has a night-raiding monster, and a hero who tears its arm off. It has that monster’s mother living at the bottom of a lake, into which the hero dives to battle her. It has a dragon guarding a hoard of treasure. Tolkien was a professor of Old English (sometimes called Anglo Saxon). He mined Beowulf and the eddas and sagas for his creations. He didn’t invent orcs. He just made his orcs his own.

My orcs aren’t like his. They’re salt of the earth types—always up for a scrap, of course, but just as ready for a good party (be sure to go easy on the Orcish Ale, it’s powerful stuff). For insight into an Orc Mating Ritual, see the free chapter available at my website.

Magic woven with words and music

I once met Charles Aznavour, the French singer. When asked about his influences, he said “We are all products of the others. It is impossible for anyone to emerge fully formed from the forest.” Tolkien ploughed the same furrows as Wagner, whose Ring Cycle inspired him—and me. The Ring’s astonishing music transports us to realms of pure feeling where words are redundant. And isn’t that what we all experience when we lose ourselves in the magic? In the game?

Enchantment.

The heart of that word is chant. The song is sung. The magic spell is woven with words and music. A “spell” derives from the idea that anyone who could write, and thus spell, had a power that the illiterate did not. What is more spellbinding than music? Music is far older than speech. Birds and animals communicate by sound without words. The deep magic, from the long ages before history, lives on in music.

The circle of music and fantasy and gaming becomes complete when we give games the respect they deserve. Play is as important a strand of life as work. Children learn through play. Military strategists try out their plans in war games. Mathematicians study game theory. We play, or watch, sports and games and invest ourselves in the players and teams, never knowing how each event will turn out. And what is drama, but a play? Stage play, screenplay, teleplay? We willingly suspend our disbelief and enter into the story with the actors—or, in an RPG, as our own heroes.

Games are our gateway into the unknown, both IRL (In Real Life) and in RPGs. Just as a piece of music can speak to our souls, and take us off and away, so can games and gaming free us from the constraints of reality.

And off we Boldly Go. What is beyond that hill? In that cave? Over that rainbow?

Well, why not take a look?

Just be sure to keep an eye out for ogres.

Images by: Joey kwok & Clem Onojeghuo on Unsplash

Leave a Reply