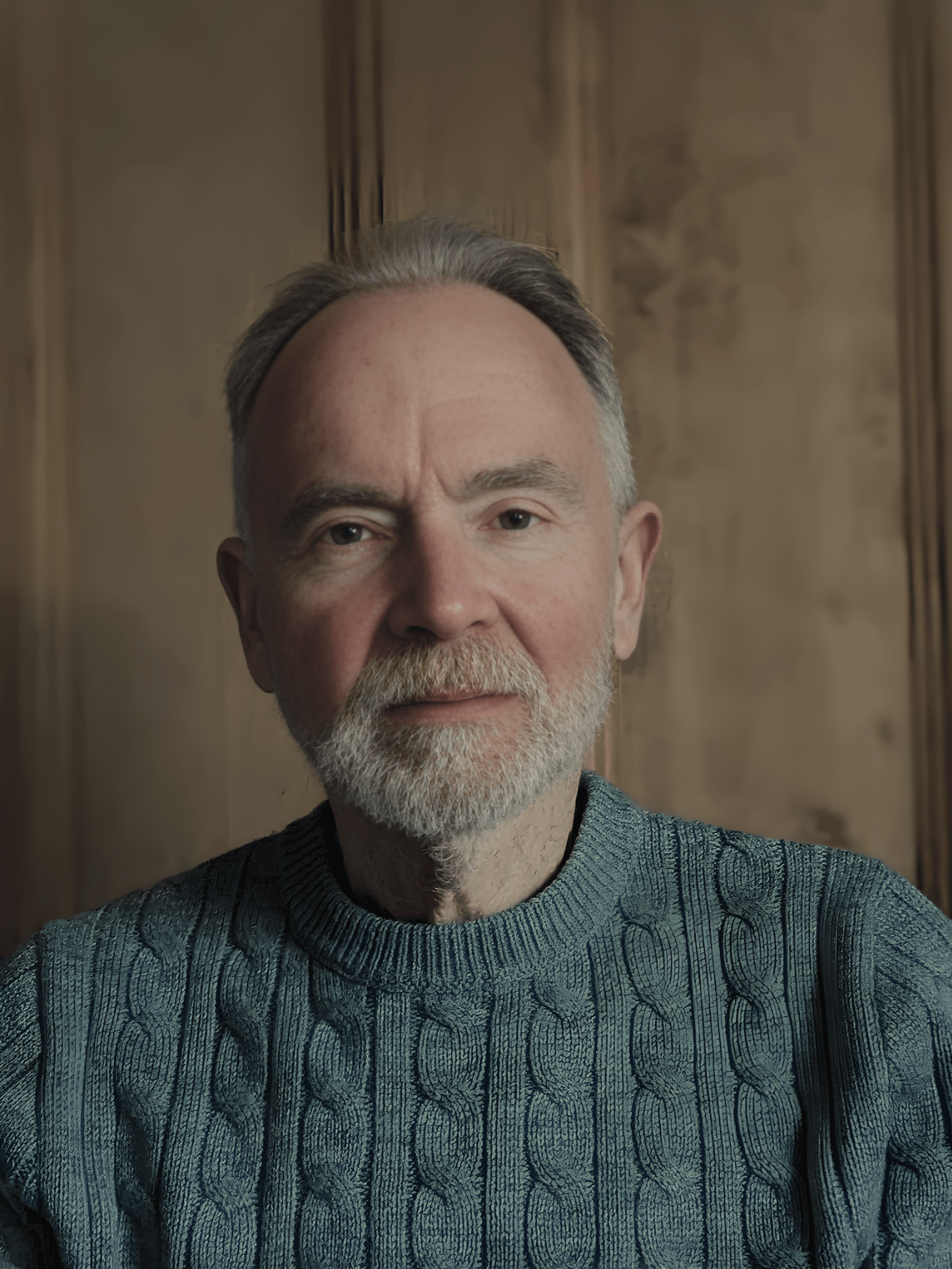

A trip to Australia and an ominous street name sent Dominic Miles’s imagination aflutter. His forthcoming book Blood Creek is the result: it follows a woman coming to terms with her grief while learning about the dark past of her new hometown. But how can you tell these tales while maintaining respect for what really happened?

My fantasy novel Blood Creek is set in Australia in two time periods: the present day and the 1860s. It follows two characters who happen to encounter each other across time and space. They are linked by the dark history of the creek and the atrocity that happened there. Though the book is fiction, it is based on real events.Â

The idea for the book came to me when I was spending some time with friends in Queensland, Australia. I went for a run one morning and I ended up on a plank bridge over a narrow creek, which flowed into a local lake. When I looked on a map, I found out that the creek was called Murdering Creek. Intrigued by such a dramatic and rather ominous name, I decided to find out about it.

I discovered that the creek had been so named after a massacre perpetrated by local white settlers against the indigenous tribe of the area, who had been ambushed while fishing at the mouth of the creek. The few details known about the event can be found in the database produced by the University of Newcastle in New South Wales. An impressive and exhaustive piece of research, it has listed every documented event of the sort from 1794 to 1928. The database lists over 400 massacres, which resulted more than 10,000 deaths. The researchers recognise that this is a conservative estimate, and there were many more undocumented massacres, of course, which have been lost to history. Massacres were often covered up by the colonists, sometimes euphemistically referred to as “dispersal†or “clearancesâ€. It was exceedingly rare for any colonist to be brought to justice for such events. The database can be read as a dark parallel history of Australia, a counterpoint to the sentiments of Advance Australia Fair.Â

“Brutal, bloody affairs”

I had some previous, but vague, knowledge that such things had happened. Colonial histories are, after all, usually brutal, bloody affairs, but I was taken aback by the scale and extent of the slaughter of the indigenous peoples of Australia and the way that it was often carried out in quite a systematic way, either directly by the colonial authorities or with their tacit approval. It is estimated that some 90% of the Aboriginal population of Australia was eradicated between the landing of First Fleet in 1787 and Federation in 1901 – a truly staggering figure.

The bare facts of the Murdering Creek massacre are that, following conflicts over the encroachment of cattle on their land, in February or March 1862, the manager of a local cattle station and other stockmen lured a group of Gubbi Gubbi people fishing in the creek into an ambush, opening fire on them and, in the process, killing at least 25 of them, probably most of the group. The types of weapons available to the stockmen at that date – breech loading rifles and revolvers – made such slaughter possible. The killing of so many people from what were often small nomadic groups would have had a disastrous effect on the wider community; it seems that most of the survivors dispersed to other areas, an outcome the stockmen had probably intended.

As in most of these events, there was an attempt to cover things up and the story only came out years later.

Handling the writer’s dilemma

Though the inspiration for my book came from this real event, I was faced with the writer’s dilemma: how do you tell a story which takes place in a community that you are not a member of, and which has its own taboos and internal rules about representation of past peoples and events?

My answer to this question was to fictionalise the story and the people involved in it, including the local people. By necessity, the story unfolds in an alternative or parallel world to the real historical one, in a similar geographical setting. Murdering Creek became Blood Creek, and I populated it with my own characters.

In writing about Eliza, I wanted to create a character who is on the margins of the white and local indigenous community, a character who inhabits two societies with all the problems inherent in this. This was partly to do with the fact that I felt I didn’t have the cultural knowledge or understanding to write about a local indigenous girl, but also because Eliza represents the sort of individual that appears in such colonial societies, neither fully one thing or another. Eliza’s relationship with Jane Cleary, the missionary, is representative of the other face of white colonialism – not as brutal or exploitative as the stockmen, but still patronising to the local people and their culture, and imbued with ideas about the superiority of the white race.

Cassie is another person, marginalised externally by the fact that she is in a different country and internally by grief. Putting the two together was where the novelist’s sleight of hand takes over and their stories become entwined. Both young women are destined to come to the aid of the other in quite different ways.

There’s a footnote to the story. The area around Murdering Creek – which was once bush – has become a suburb of upmarket houses on large tracts of land. Some of the local residents, living on or near Murdering Creek Road, are not particularly happy with the name and its negative connations and want it changed. So far, the local council has not agreed to such a move, but who knows for how long they’ll hold out?Â

Blood Creek will be released via The Book Guild on 28 November; pre-order it here.