We’ve implemented some new protocols around sending us messages via this website. Please email website “at” britishfantasysociety “dot” org for any issues.

For all things fantasy, horror, and speculative fiction

-

Announcement:

Writing Fantasy for Children

Younger readers have certain expectations and needs from their books, and there is plenty of perceived wisdom about how authors should work within those boundaries. Ahead of the release of her novel The Butterflies of Meadow Hill Manor next week, fantasy author Stefanie Parks shares her tips for writing fantasy for children—as well as the rules she ignored!

For as long as I can remember, I have read, written, and dreamed fantasy. I began writing stories around the age of 8, the target audience being myself, my mother (who was, and still is, my biggest fan) and—occasionally—the family dog.

As an adult, I eventually decided to dip my toes into the publishing world and was surprised and delighted when The Book Guild agreed to take on one of my stories. In celebration of its release on 28 November, I wanted to share some of my tips for writing fantasy for children.

My top 10 tips

Write what you love

Knowing why you’re writing and why it gives you joy is important. As a child, my approach was simply to write stories that I knew I would enjoy escaping to later on. This still thrills me as an adult, and I continue to write stories that my younger self would love.

Read

An obvious tip and relevant regardless of the age range or genre you’re writing for. I read multiple children’s fantasy books. This helps me learn more about the genre, what I like and love, but also what I dislike and want to avoid. I also read a wide range of horror, crime, historical fiction, and the odd bestseller. I try to read as widely as possible to broaden my experience and deepen my imagination.

Write understandable storylines

Whilst children’s stories can and should embrace a whole spectrum of emotions and themes, it’s important to write storylines that are accessible and understandable. If they become too complex or unnecessarily intricate, then younger readers may switch off. I worked as a primary school teacher for many years and the books that were requested over and again were the ones that were easily understood.

Introduce an element of magic

Children’s fantasy stories contain magic. What kind of magic will your story include? Depending on your subgenre, you might be writing about magical creatures, worlds, or entire magic systems. Personally, I love contemporary fantasy stories where characters live in our everyday world with an added element of magic that not everyone is aware of. In my upcoming book, the magical element is focused around butterflies.

Know your back story

There will be a huge amount of information that doesn’t get written in your book. It’s important that you, as the author, know this information. When authors haven’t done their wider thinking around the backstory it can show in their work. For every hour I spend writing, I probably spend three hours just thinking, pondering on characters, posing myself questions and exploring the limitations of the magical systems and worlds I’ve created. These can be simple, practical questions or huge philosophical concepts. What would happen if X occurs? Is Y a possibility in this story? Why doesn’t Z act in this way? However you approach this, your thinking fills out your world and characters, and impacts upon the final story by giving it a more complete feel.

Get feedback from children

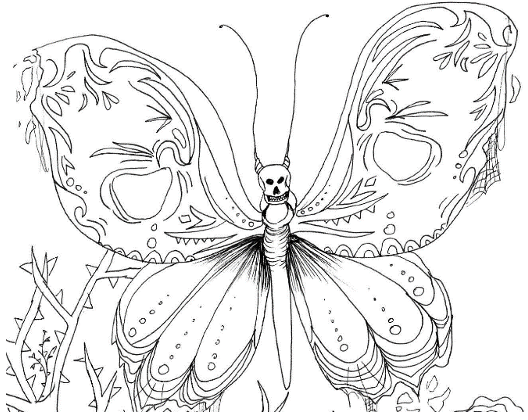

They will be wonderfully (and painfully) honest, and as the intended audience it’s great to get their input on your initial drafts. I was lucky enough to have a connection with a talented young artist named Imogen (12). I gave her a copy of the book and asked her to develop some images of the butterflies. The results were excellent (one of them is pictured to the right) and it was a great insight into how children might imagine the butterflies.

Use organisational systems that work for you

Another tip that isn’t really specific to children’s writing but is something I’ve found essential. If you’re not a ‘pantser’ then you’ll need to use some sort of system to organise your thinking—find what works for you. I read various blogs around this topic and tried a range of systems from spreadsheets and story arcs to tick-lists. In the end I discovered that what works best for me is simple notes and sketches so, despite having zero artistic skill, I generally plan by using bullet pointed words or short phrases, and then sketching any accompanying images. It must look dreadful to anyone else, but it’s what works for me.

Write about relatable issues

What annoyed you as a child? Chances are those same things irritate and challenge today’s children too. So whilst most children will hopefully not relate to the trauma that occurs in my book, they may well relate to some of the other issues within it: feeling frustrated with parents, being the awkward newbie at school, trying to make friends, etc.

Connect with the writing community

I wish I had learned this sooner! It was only once I’d had a manuscript accepted that I suddenly realised how alone I was. I started actively looking around and discovered a wonderful community of writers. I’ve now joined various digital fantasy groups and societies—including the BFS, of course! I also joined a local children’s writing group and started listening to writing podcasts; both helped me to connect with other writers. If there was one thing I wish I’d done sooner, it’s this!

Take your time

When writing a fantasy story, the temptation to showcase absolutely every magical aspect of your system or world immediately is strong! Resist this urge. Young readers can enjoy seeing the magic unfold bit by bit, and will also enjoy guessing at the other aspects until they are revealed. Stories that over inform or describe everything very quickly can be a little off-putting to read. As a reader, I enjoy connecting the dots myself and am happy to learn about an author’s magical creations as they unfold over the course of a book or series.

But… there was also advice I chose to ignore

Rules I ignored included these.

Stay away from topics that are too dark or upsetting

This is possibly true for very young children, but most primary-aged children are more than capable of reading and dealing with tough topics such as death or grief. They experience a whole range of human emotions, just like adults, and books can provide a great way to open up those discussions. As a teacher, I was often amazed by the depth of thinking and conversation that would come from our story time sessions.

Ensure children’s books have a clear moral, or teach a life lesson

I think this all comes back to your ‘why’. If you’re writing a book with the purpose of teaching a life lesson then great—but if you’re writing a book for the purpose of enjoyment then I would argue that including a life lesson isn’t essential. I also believe that reading is a fantastic way of learning empathy—how else do we get inside other people’s heads and understand their points of view? I think all books teach us empathy which is a great lesson.

Make sure your characters are clearly described, or paint a picture

I do not always do this, although some of the feedback I’ve had from children suggests they would like me to. When I read, I enjoy creating pictures of the characters for myself so tend to provide very little detail in this area when I write. I think there are only about two lines of description for the protagonist in my upcoming book. This won’t be everyone’s cup of tea, but it is a reflection of tip number one – write what you love.

Ultimately, it’s all about your own preferences

The internet is full of helpful writing tips; the dos, don’ts, always…, and never… lists are easy to access and are often very helpful. However, these are always subject to an individual’s preference and style. The lists above are a case in point: they are my preference and style. If you know why you’re writing and why it brings you joy, get it written and you’ll figure the rest out along the way.

The Butterflies of Meadow Hill Manor, by Stefanie Parks, is out on 28 November; pre-order it here.

Images by: __ drz __, Joshua J. Cotten, and Neenu Vimalkumar

Meet the guest author…

Stefanie Parks was born and raised in the beautiful county of Derbyshire which became the inspiration and setting for her stories. She trained as a teacher at Derby University and after working locally for five years, decided to explore the world with her husband. Together they worked their way around a handful of countries and are currently living in Christchurch, New Zealand. Stefanie has written consistently during her travels; her stories always linking her back to her homeland.

Explore the blog:

Blog categories:

Latest Posts:

Tags:

#featured (56) #science fiction (25) Book Review (264) events (44) Fantasy (231) Graphic Novel (13) horror (136) Members (62) Orbit Books (48) profile (43) Romance (17) Science Fiction (50) short stories (28) Titan Books (52) TV Review (15)

All reviews

Latest Reviews:

- THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND by William Hope Hodgson

- Monstrum by Lottie Mills

- Mood Swings by Dave Jeffery

- Yoke of Stars by R.B. Lemberg

- Hera by Jennifer Saint

- The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness

- RETURN OF THE DWARVES By Markus Heitz

- Delicious in Dungeon

- Toxxic by Jane Hennigan

- THIS ISLAND EARTH: 8 FEATURES FROM THE DRIVE-IN By Dale Bailey

Review tags:

#featured (2) Action (4) Adventure (4) Book Review (28) Fantasy (18) Featured (2) Feminist (2) Gothic Horror (3) Horror (14) Magic (3) Orbit Books (3) Romance (6) Science Fiction (5) Swords and Sorcery (2) Titan Books (7)