In his semi-regular column on the TV that made us SFFH fans, Gary Couzens revisits Escape Into Night—a children’s serial adapted from Catherine Storr’s novel Marianne Dreams, and later remade as the film Paperhouse.

Something often said about those serials made for children (okay, older children) in the 1960s and 1970s is that they weren’t afraid to scare their audiences. And so it is with Escape into Night, a six-part serial broadcast on the ITV network at 5.20pm on Wednesdays from 19 April 1972. It appears not to have been repeated, and no longer exists in its original form, but when it was released on DVD in 2009 it carried a 12 certificate.

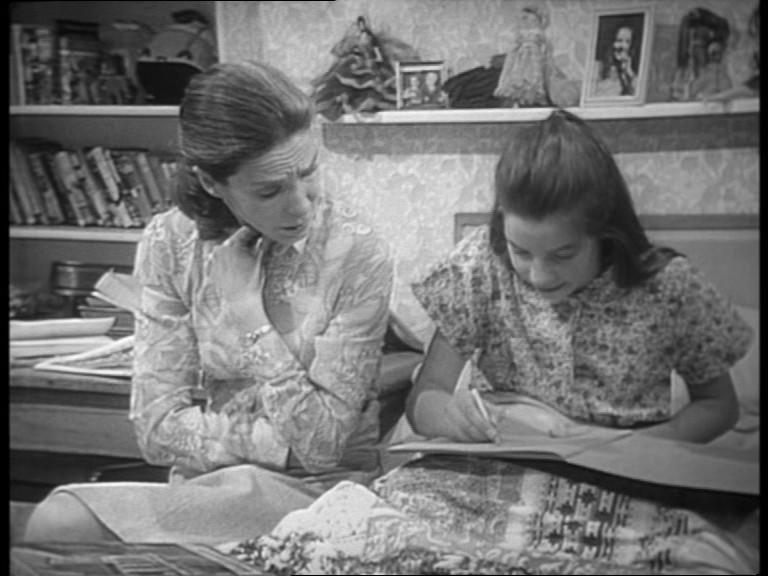

Marianne (Vikki Chambers) is confined to bed after breaking her leg in a riding accident. Her father is away on work, so she is alone with her mother (Sonia Graham)—other than visits from Dr Burton (Edmund Pegge) and teacher Miss Chesterfield (Patricia Maynard). Bored and frustrated due to her inactivity, Marianne takes refuge in a drawing book. At night, she dreams of the house she drew in the book and a boy who lives inside it. This is Mark (Steven Jones), another pupil of Miss Chesterfield who is also confined to bed. But as time progresses, things change in her dream world and Marianne and Mark are soon under threat…

The source material

Escape into Night was adapted by Ruth Boswell from Catherine Storr’s 1958 novel Marianne Dreams. Storr (1913-2001) began writing for her daughters, one of whom, Polly, became the heroine of a series for younger readers, beginning with Clever Polly and the Stupid Wolf (1955). Marianne Dreams is for relatively older readers, what would today be called middle-grade, as Marianne turns ten in the opening chapter. Marianne and Mark are too young for any romance which might feature if they had been older, making this—the serial perhaps more than the novel—a story aimed at all sexes rather than specifically skewing to just one.

The Changes, which I covered here last month, was a serial with a female lead and in its second half a male co-lead, but was not so much “for girls” and was watched by boys as well. There, the two leads have a platonic friendship. And so it is with Escape into Night. In the novel, Marianne and Mark never meet outside her dream space. The TV serial ends with a brief encounter in real life, an exchange of glances, a moment of recognition.

The serial was made by ATV, the then-ITV franchise for the Midlands. With a notably interior source novel, Escape into Night is almost entirely studio-bound other than a short scene depicting Marianne’s riding accident before the opening credits of the first episode, and the final scene mentioned above, shot at Barr Beacon, near Aldridge. Much of the action takes place in two sets: Marianne’s bedroom and the inside and outside of her dream house. The serial is generally faithful to the novel, though the unspecified illness Marianne suffers in the novel becomes that likely more televisual accident.

There was some inevitable updating in the thirteen or so years since the novel was published: for one, Marianne’s maths lessons don’t involve adding and subtracting pounds, shillings and pence. The serial does hark back to a time where doctors regularly made home visits, even once in the middle of the night.

As the serial is called Escape into Night, we may not want to escape to wherever Marianne goes, and certainly not when those slowly-moving rocks with blinking eyes make their appearance and steadily approach. (In the novel they are referred to as THEM – Storr’s capitals.)

The performers

The cast, apart from some uncredited extras in the location scenes, numbers just five. There are solid performances from the three adults, all of whom were familiar faces on the small screen. Three years later, Sonia Graham would play the heroine’s mother in the first episode of The Changes: she died in 2018 at the age of eighty-eight.

Patricia Maynard had played Cora the previous year in the well-remembered BBC serial of The Last of the Mohicans, and genre fans of the time will certainly remember her as the villain Hilda Winters in Tom Baker’s first Doctor Who story, Robot, two years later. She also co-wrote the theme song of Minder, as she was at the time married to that show’s star, Dennis Waterman.

Edmund Pegge is an Australian actor who began his career there in the early 1960s before relocating to the UK like many actors did for the greater opportunities, and he has divided his time between the two countries.

The two children had never acted before and were cast after extensive auditions in local schools. Vikki Chambers was eleven and came from Solihull; Steven Jones was thirteen from Acocks Green. Jones never acted again, but Chambers from the end of the 1970s continued an adult acting career, including regular roles in Coronation Street and the nursing drama Angels. There’s a slight stage-school edge to both of their performances, even if they weren’t actual stage-school kids. That said, Chambers does an able job given that the entire serial rests on her. As in the novel, the serial doesn’t softpedal Marianne’s boredom and occasional bouts of bad temper and brattiness that exasperate her mother in particular.

The colour version lost to history

Escape into Night is well remembered by those who saw it, either on original broadcast or on DVD. However, it ran into an issue common in television of the time. By 1972, both BBC channels and all ITV regions except Channel were broadcasting in colour, although the great majority of British households still had black and white sets. It wasn’t until 1976 that the proportion of homes with colour sets reached fifty percent.

Television contracts usually covered only one showing with a possible repeat within two years. As much television was felt to be surplus to requirements with no lasting value, original videotapes were routinely wiped and reused. Escape into Night was made on colour videotape and was duly wiped at some point after broadcast. It survives because black and white telerecordings were made, shot on 16mm film and used for selling programmes overseas. These recordings were the basis of the DVD release. At least the serial does survive, as many other programmes of the time are partially or completely lost.

Of all Storr’s books, Marianne Dreams is the one which has had the greatest longevity. She wrote a sequel, Marianne and Mark, published in 1960. While Marianne Dreams is still in print, the sequel is not. Set in Brighton (where Marianne convalesced in the first novel) and Eastbourne, this novel raises an interesting question, given that it’s of a different reading age to the original as Marianne and Mark are now fifteen, so in today’s terms the novel would be young-adult rather than middle-grade. It’s also in a different genre, barely fantasy despite some significant input from a fortune-teller and the question whether Mark remembers the dreams or if they were only experienced by Marianne. With the characters being older, there is boy-girl interaction of a less platonic kind than in the original.

Storr disagreed that the novel was not fantasy, saying “I wrote that because I’d always wanted to write on the Macbeth theme – if you are told that something is going to happen to you, you make it happen. That was what the book was supposed to be about and there is a very good example of using fantasy.”

Later, Storr wrote the libretto for an operatic adaptation of Marianne Dreams in 1999, and in 2007, after her death, Moira Buffini adapted the novel for stage. And, in 1988, there was another screen adaptation.

The ’80s update: Paperhouse

With a script by Matthew Jacobs, the story now known as Paperhouse was the debut big-screen film from Bernard Rose, who had previously made two films for the BBC and several pop videos. (Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Relax” and Bronski Beat’s “Smalltown Boy” were among them.) The first thing to notice is that, more than Escape into Night, it makes significant changes to the story. Some of this is no doubt due to updating, from the late 1950s to the late 1980s.

The eleven-year-old heroine, now called Anna (Charlotte Burke, actually aged thirteen), is in bed due to glandular fever. (This apparently confused US audiences who knew the disease as mononucleosis). She no longer has a visiting governess/teacher and the role of the doctor, now a woman (played by Gemma Jones), is reduced, though it’s through her that Anna hears about Marc (spelling changed). Glenne Headly, an American playing with an English accent, plays Anna’s mother.

Again the ending is different (I won’t say more, to avoid spoilers), to rather sentimental effect. However, the major change is in the role of the father. Ben Cross has second billing despite not appearing until after the halfway mark other than in still photographs. In both Marianne Dreams and Escape into Night, he is an absent figure, away from home for work reasons; this time, instead of those ambulant stones, he is the threat in dream space.

Paperhouse was well-received by those who saw it, but commercially it fell between two stools: a film centred on a child which because of its horror content couldn’t be seen by them. Charlotte Burke, who is impressive in her only acting role, was not old enough to see it on its release, as it had a 15 certificate. It still has, retaining it on DVD in 2001 despite the 12 certificate being available then.

Bernard Rose went on to a diverse career, including literary adaptations (Anna Karenina, 1997), historical biopics (Immortal Beloved, about Beethoven, 1994) and other excursions into horror – the 1992 version of Candyman and a 2015 take on Frankenstein among them. Elliott Spiers, who played Marc, went on to other acting roles on television, and one other feature film, Taxandria (1994). Sadly he died before the latter was released, aged just twenty.

Marianne Dreams is a novel which clearly still has life in it, and Escape into Night, while it’s stylistically very much of its time, still works as a creepy story for younger viewers. Maybe they should keep the light on afterwards.

Do you remember Escape Into Night? Or maybe saw Paperhouse? Let us know what you thought in the comments below ⬇️

One response to “The TV That Made Us: Escape Into Night (1972)”

Paperhouse terrified me as a kid! I had no idea it had all this history behind it. I didn’t realise it was Bernard Rose either, which would explain why it was so effective at scaring the socks off me. Thanks for this!