This World Autism Awareness Day, BFS Secretary David Green shares his experience of being an autistic writer in the publishing world, and calls for more support for neurodivergent people in the industry.

Recently, the tired and harmful – not to mention factually incorrect and easily disprovable – rhetoric of “vaccines cause autism” has reared its ugly, pathetic head again. I won’t go into the reasons why this has happened, besides saying you probably don’t need three guesses to nail down where this hateful, ignorant speech is coming from.

It’s depressing, though. Frustrating, too. And not just because of how willfully misleading and insidious such salacious misinformation is. It’s depressing because of how little push back there has been, and it’s depressing because that’s exactly what I expected.

Why? Despite it being 2025, and autism was first diagnosed in the 1940s (after being coined as a form of schizophrenia in 1911), there is still a whole lot of confusion and a general lack of education surrounding autism.

And, sometimes, I just don’t think people care all that much unless there is someone close to them with autism. I’d love to be proved wrong on this.

So, let’s get one thing clear: vaccines don’t ‘cause’ autism. You cannot ‘catch’ autism. People don’t ‘have’ autism, like its some disease, or a condition to manage with symptoms medicine will alleviate. And no, not everyone is ‘a little bit on the spectrum’. There is no spectrum. Nor is autism a disorder. We’re not the missing jigsaw piece in a puzzle. Our brains are just different to neurotypical people. We process stimuli in a divergent way, and express ourselves accordingly.

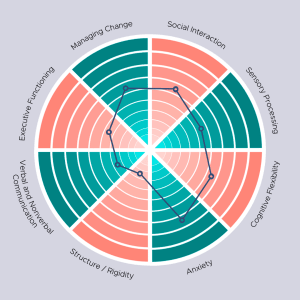

Autistic people are born autistic. In a lot of cases, the profile of that autistic person – a pie chart and not a spectrum detailing the person’s strengths and challenges across a diversity of areas such as communication, socialising, sensory issues and more – aren’t readily apparent until they’re older. And, usually, those with more support needs are identified earlier.

(As an aside, the language surrounding autism is ever-evolving and is a conversation. I’ve no problem with people using outdated terminology from a place of good faith. I’m pretty sure I’ve used language surrounding autism that other autistic people might not agree with, and I’m always willing to listen and learn.)

All of this might be news to some reading. That’s fine. Since receiving my diagnosis (and having someone near and dear to me in my life being diagnosed as autistic at a very early stage of their development), I made the decision to talk about autism whenever and wherever I can. But I’d like to circle back to this sentence, and why this article is appearing on a place concerned with writing:

‘And, usually, those with more support needs are identified earlier.’

Autistic representation in fiction matters

The sad fact of autism, is that autism is judged on how much of an issue an autistic person is causing for someone else, be they a neurotypical person, a school, an institution or a place of work. Some may not agree with this, but, in my experience, it’s an undeniable, unyielding fact.

Let’s look at the (ever-evolving) language around autism. People still use ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) despite a lot of autistic people asking, please, pretty please, not to. People still use the term ‘the spectrum’, adding ‘high spectrum’ and ‘low spectrum’ to the mix.

Why?

Because those ‘lower on the spectrum’ cause people more issues and are more easily identifiable for said neurotypicals, schools, institutions and places of work. These autistic people need – and in my opinion don’t get enough (none of us do) – more support on a daily basis. These autistic people may not communicate through speech (and are termed as non-communicative as if all our communication as a species is done through speech), they may have more of a challenge when faced with sensory overloads or changes in routine.

But this doesn’t mean ‘high-functioning’ autistic people don’t face those same challenges. Those deemed ‘high-functioning’ (like me) simply are able to mask their responses to such things in a way that’s acceptable to everyone else. We mask our responses to noise, to touch, to smell, to changes in routine, to mystifying social ‘norms’ until we’re safely away from the public eye where we can meltdown without bothering anyone else so we’re not a burden.

Thus, we’re christened as ‘high-functioning’ because we’re causing fewer problems. High-fives all around. Go us.

But, again, why are you reading this here?

Because there are lots of autistic people with creative aspirations, all with different autistic profiles, across the publishing world. There are lots of people like me, and lots of people who are autistic not like me, striving to get our voices, and our stories, heard.

Yes, despite what the ‘vaccines cause autism’ crowd might tell you, autistic people are creative. We’re imaginative. Hey, we even have empathy (too much to know what to do with, which causes a meltdown as we’ve been trained not to show our emotions as they’re not appropriate) and – guess what? – we’re not all walking supercomputers with super powers to help us navigate the big bad world.

We’re people. Autistic people. And we have dreams and goals like anyone else.

And there is little support for us in the publishing world.

Navigating publishing as an autistic person

I’ve detailed my writing experience and the challenges of the submission process before, but the challenges go deeper than that. All systems in society are designed by neurotypicals for neurotypicals, and most institutions and said systems are easier to navigate for white, hetero, neurotypical, middle-class to upper-class men. That shouldn’t be news to anyone.

But the publishing world in particular is nightmarish for autistic people with their stories to tell. There’s a general lack of information on how to do the thing, from querying in the hope of finding your agent, and then the submissions process and beyond. If you want to get into self-publishing, it’s even worse in some regards. You become a small-business owner, doing the entire publishing business alone, from writing to trying to tackle the mystifying enigma that is advertising (which many successful self-publishers horde their skills and knowledge like Smaug clutching his treasures, because a lot of it comes to down to cold, hard cash. The more money you can pump into your business, the better it will do. Autistic people, for a variety of reasons, don’t tend to have a lot of accumulated and disposable wealth). At least with the traditional route, you might get an agent in your corner (and mine is wonderful and supportive and I never thank her enough. If you’re reading this, thank you.)

And the submissions process… Not every book will win out. That’s fine. Sometimes it isn’t the right time. Sometimes, perhaps, the book just doesn’t work. But when an autistic person is writing about their experience – you know, this ‘own-voice’ thing we’re told people want – please don’t tell us things like, ‘I wish the ‘neuro diverse’ character was more traditional’ or ‘I don’t like how the ‘neuro diverse’ character couldn’t understand X’. Or, maybe, be a little more creative than ‘I couldn’t connect with the autistic protagonist’. Not connecting with someone with autism isn’t the fault of the autistic person. Perhaps a touch of empathy would go a long way. Isn’t storytelling meant to be a gateway to understand those not yourself?

Compounding matters, there is no organisation dedicated to helping autistic and neurodivergent writers. None. And I’ve looked. The British Fantasy Society has done good work in being a safe, welcoming place for autistic creatives – alongside its brilliant and much-needed outreach programme – but we lack something like the Future Worlds Prize.

Do you know about Future Worlds Prize? Take a look here. They are a wonderful and effective organisation who champion their writers of colour, striving to gain a platform for their writers’ voices and talents. Supporting them every step of the way. I love them. Honestly, I wish there were places like Future Worlds Prize for LGBTQIA+ writers, too. More organisations designed to support certain underrepresented voices in our industry would only be a good move (and a shout out to Stewart Hotston for his work in this regard, too).

But you know what? I would dearly love something similar for autistic people. A place we can go to for advice and support. A place that fights for us. A place that educates others in the industry about autism. Because we’re not going away. We have dreams. We have goals. But, I would suggest, we lack the tools and the support to achieve them. We lack the platform for our voices and our stories so people can be our allies when we fight against hate speech and misinformation.

We need to tell our autistic stories, and people need to read them. Because we’re not all Sheldon Cooper (ugh) or Rain Man. And, no, Data and Spock aren’t autistic. One is literally an android, and the other is an alien.

Autistic people are people. Human people. We just need a little more support.