We’ve implemented some new protocols around sending us messages via this website. Please email website “at” britishfantasysociety “dot” org for any issues.

For all things fantasy, horror, and speculative fiction

-

Announcement:

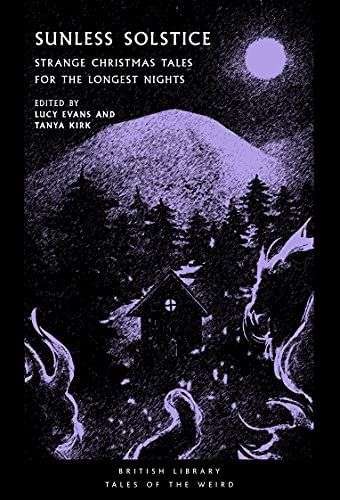

SUNLESS SOLSTICE: Strange Christmas Tales for the Longest Nights, edited by Lucy Evans and Tanya Kirk from @BL_Publishing

SUNLESS SOLSTICE: Strange Christmas Tales for the Longest Nights, edited by Lucy Evans and Tanya Kirk

British Library Press, 288-page p/b, £8.99

Reviewed by Pauline Morgan

Since Christmas is close to the longest night of the year and the period is often one of cold, it was inevitable that stories were told around the fires to take minds away from the weather outside. So arose a penchant for stories based around the time of the telling. Setting them in the kind of weather that raged outside was also inevitable. That led to scary ghost stories. While not every one of the stories in this volume is set at Christmas, they all have characters pitting themselves against the elements.

Not many of these tales take the traditional form of being told to a group of friends around a fire at Christmas. ‘Ganthony’s Wife’ by E. Temple Thurston (1926) is one that does. One of the groups gathered tells the story of the woman Ganthony met and married before taking her to India, where she died. Her ghost makes periodic appearances to her husband. ‘The Ghost At The Cross-Roads’ by Frederick Manley (1893) is the story of a stranger turning up at a party at Christmas and tells a tale of being lost but coming across a man at a crossroads with whom he plays cards.

A couple of the stories involve vindictive wives. In ‘The Apple Tree’ by Daphne Du Maurier (1952), the widower, who is the focal character, is relieved when his wife dies, but he has not appreciated how much she has done to try to please him. Although it is never stated, the assumption is that her spirit has taken up residence in a sickly apple tree and exacts her revenge in an escalating series of events. ‘The Third Shadow’ by H. Russell Wakefield (1950) is not set at Christmas but in the snowy Alps. When Brown marries, he does not expect his new bride to insist on climbing with him. The problem is that she is hopeless at it. When she dies in a climbing accident – though there is some speculation about the veracity of the incident, his friend encourages him to go back to the mountains. There is a suspicion that her ghost is the cause of his later accident.

Several stories happen at Christmas. In ‘The Visiting Star’ by Robert Aickman (1966), the actress Arabella Rokeby has agreed to star in a play on Christmas Eve in a declining former mining town. Colvin, the narrator, is staying in the hotel when the star and her companion are to lodge. The strangeness that gradually develops starts with the appearance of Mr Superbus at the hotel. He leaves two heavy suitcases in his room and doesn’t complain when the maid forgets to make up his bed. It is a Christmas party in ‘The Man Who Came Back’ by Margery Lawrence (1935), where the hostess has arranged a séance as entertainment for her guests. As often happens in such cases, it is the sceptic of the party who has the most to lose if the medium turns out to have genuine talent. In a much lighter vein is ‘Mr Huffam’ by Hugh Walpole (1933). Tubby Winsloe saves a stranger who almost walks in front of a car, then invites him home for tea. Mr Huffam turns the house upside down by organising a children’s party. There are enough clues within the story for the intelligent reader to determine who Mr Huffam is.

While Tubby had not been looking forward to a happy Christmas before meeting Mr Huffam, the title character in ‘The Leaf-Sweeper’ by Muriel Spark (1956) has tried to organise an abolition of Christmas since he was a child. In later years, the narrator discovers Johnnie is an inmate at the local asylum, but every Christmas, his ghost (who loves Christmas) goes to visit his aunt.

In two stories, Christmas is not the essential part of the tale. In ‘The Blue Room’ by Lettice Galbraith (1897), it is a Christmas gathering which means that the Blue Room needs to be occupied despite it normally being left empty since the lady of the house had died there many years ago. At this gathering, another woman dies in the room. The curse of the room doesn’t seem to affect the men who sleep there. Unusually, this story is narrated by a housemaid. ‘The Black Cat’ by W. J. Wintle (1921) is also only incidentally a Christmas story. Sydney has a phobia of cats. He appears to be stalked by the presence of a cat. He has also noted his curiosity about the number 24. It crops up many times in his life. Perhaps it is just a coincidence that Christmas Eve is 24th December when events come to a head.

Most of us still send (or give) Christmas cards. The narrator in ‘A Fall Of Snow’ by James Turner (1974) is unsettled by the ones showing two boys tobogganing and not just because it is inaccurate. When he was ten, he spent Christmas in Norfolk with a cousin and, on a toboggan run, saw something that haunted him for years.

‘On The Northern Ice’ by Elia Wilkinson Peattie (1898) is another story that doesn’t feature Christmas but is set amongst ice and snow. Ralf Hagadorn is determined to arrive in time for his best friend’s wedding. As he skates across the ice at night, he encounters another skater and follows her, hoping to catch her up, unaware that the spirit is leading him out of danger.

While all these are excellent stories, they are also a product of the times in which they were written and mostly reflected the author’s social class. Many have settings, like the country house, that are no longer part of our landscape. Read from this perspective, they give a glimpse of Christmases that no longer exist.

Explore the blog:

Blog categories:

Latest Posts:

Tags:

#featured (56) #science fiction (25) Book Review (264) events (44) Fantasy (231) Graphic Novel (13) horror (136) Members (62) Orbit Books (48) profile (43) Romance (17) Science Fiction (50) short stories (28) Titan Books (52) TV Review (15)

All reviews

Latest Reviews:

- THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND by William Hope Hodgson

- Monstrum by Lottie Mills

- Mood Swings by Dave Jeffery

- Yoke of Stars by R.B. Lemberg

- Hera by Jennifer Saint

- The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness

- RETURN OF THE DWARVES By Markus Heitz

- Delicious in Dungeon

- Toxxic by Jane Hennigan

- THIS ISLAND EARTH: 8 FEATURES FROM THE DRIVE-IN By Dale Bailey

Review tags:

#featured (2) Action (4) Adventure (4) Book Review (28) Fantasy (18) Featured (2) Feminist (2) Gothic Horror (3) Horror (14) Magic (3) Orbit Books (3) Romance (6) Science Fiction (5) Swords and Sorcery (2) Titan Books (7)