In this latest edition of her regular column, Tiffani Angus—co-author of Spec Fic for Newbies volumes 1 & 2—plays with our minds for Valentine’s.

The past few months since the US election … [no, strike that].

The past five years since the start of the pandemic … [no, not far enough back]

Since 2016’s US election and that certain UK vote … [Damnit!]

Okay, since Bowie and Prince died [Yes! That’s the right spot] things have been a bit, shall we say, uneven? Well, for some people, everything has been fine, and that is a huge privilege to have. But the past near-decade hasn’t been great for a lot of us, and with that upheaval comes mental health issues (on top of any that some of us might already have been dealing with).

Some people have been a bit hyperbolic to claim that recent history has “made them crazy†or that our governments are being run by “madmenâ€, but that’s just us taking poetic license. Because true psychological issues are nothing to be flippant about.

So many horror subgenres are about scary things out there: ghosts, werewolves, haunted houses, eldritch gods, etc. But the writing community, especially in horror, has employed human psychology and the mysteries of the human brain to ramp up the scares. This month, the Subgenre Deep Dive is opening up our skulls and peeking inside to examine Psychological Horror.

This is a condensed and tweaked version of the same section from Spec Fic for Newbies Vol 2: A Beginner’s Guide to Writing More Subgenres of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror (2024), by me and Val Nolan, out from Luna Press. Both volume 1 (2023) and volume 2 (2024) were included on Locus’s Recommended Reading List. Volume 1 was a finalist for the BSFA Best (Long) Nonfiction and the BFS Best Nonfiction awards, and Volume 2 just made the BSFA longlist. So why not check them out? Each book contains 30 subgenres and tropes from Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror, their histories, identifying elements, lists of what’s cool and pitfalls to avoid, and activities to get you writing. Plus the usual puns and snarky jokes! So, what are you waiting for? See here for purchasing links. Oh, and keep your eyes peeled for a third volume to drop Easter 2026!

This month is a look at… PSYCHOLOGICAL HORROR!

First, a bit of history

Psychological horror has at its roots our curiosity—and confusion—about how our brains work and how that scares us. To grasp this subgenre’s potential as well as to gain a better sense of how the subgenre and its tropes have developed, a very short history of the evolution of our understanding of mental health and of the development of the discipline of psychology is important.

Centuries ago, people believed that someone displaying symptoms of what we now know as a mental illness was guilty of a crime or other trespass and even possessed by demons. There was also the theory about “humours†or the four fluids (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile): in ancient Greece, “father of medicine†Hippocrates believed that depression resulted in an imbalance of the humours, and even as recently as the seventeenth century in Europe, belief in the four humours resulted in treatments such as “bloodletting, purging and vomiting†with (unsurprisingly) very low success rates. People tried to fix brains by digging directly into them via trepanning (as far back as 7,000 years ago) and by banishing the demons via exorcism.

Unfortunately, early treatments for psychological issues that actually tried to understand the illness wasn’t due to any supernatural entity—well, they were crude and abusive. Royal Bethlem Hospital, soon known as Bedlam (a word we still use today to mean chaos), was first a thirteenth-century priory “devoted to healing sick paupers†that, over the next hundred years, became specifically for those displaying mental-health issues. In 1676, the hospital relocated to Moorfields, where it remained for about 150 years.

(Image: By William Hogarth – The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=152825)

The treatments these patents endured at Bethlem and other institutions until, and even into, the early twentieth century were often inhumane because clinicians were ignorant of the underlying issues the patient was dealing with. Treatments included putting patients into induced comas, isolating or restraining them, shocking them, giving them fevers, and even spinning them as a way to counteract whatever was happening in their minds. To add insult to injury, the Bethlem building opened in 1676 was as beautiful as a palace from the outside but crumbling and wet inside, and was open to visitors who paid to see the patients, much like visiting a zoo.

Luckily, the understanding and treatment of psychological issues has evolved—but the creation of theories to describe various mental health issues is relatively recent, traced in some form to William Battie’s “Treatise on Madness†(1758), and more solidly established with Sigmund Freud’s “examination of psychopathology†and Carl Jung’s “analytic psychology†in the early twentieth century. It wasn’t until 1952 that the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders was published; the DSM is still in use today, being updated as our knowledge grows.

Now, a quick look at the evolution of psychological horror

Horror fiction depends on creating a reaction in the reader that can run the gamut from simple uncomfortableness to outright terror. Early horror novels released when our understanding of psychology was in its infancy—such as the eighteenth-century gothic tale The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole—helped forge the connection between place (haunted dwellings) and emotional mood, which we can see in hindsight as early psychological horror.

In the early-nineteenth century, Edgar Allen Poe pushed this envelope further with stories that explored our emotional extremes, such as ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ (1843), in which the protagonist is going mad believing that the heart of a man he murdered is beating under the floorboards and that other people can hear it, too. And Henry James’s novella The Turn of the Screw (1898) is still the subject of debate to decide whether the ghosts are real or figments of the governess’s imagination. In these stories, the characters are suspicious of their own senses or of other people, they aren’t sure who to trust, and their paranoia often gets the better of them.

Psychological horror became an established subgenre in the twentieth century in tandem with the growth of understanding and treatment of mental health issues. It was especially enhanced by the popularity of film, and some of the most popular psychological horror films took a chilling book and made it truly unsettling, even in a crowded cinema:

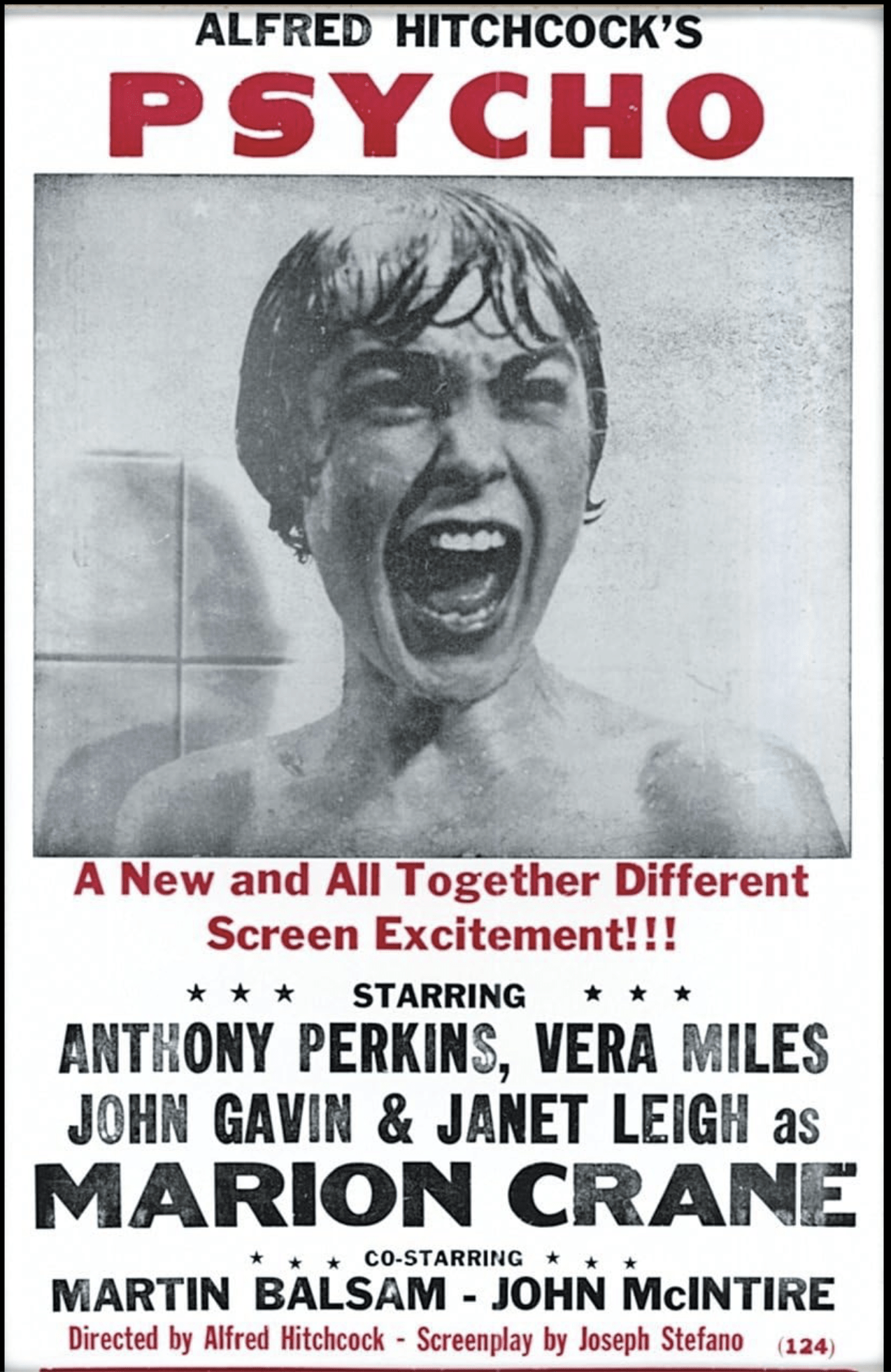

- In Psycho by Robert Bloch (1959), quickly filmed in 1960 (dir. Alfred Hitchcock), Norman Bates runs a motel, which becomes a true house of horrors when the effects of his twisted relationship with his mother, whose mummified body he keeps in the house, pushes him to commit numerous murders. Readers and viewers are kept unbalanced, not knowing until the end whether his mother is truly alive or dead.

- The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson (1959) was filmed in 1963 (dir. Robert Wise) and again for a Netflix mini-series in 2018 (dir. Mike Flanagan). While some would label this a supernatural horror story because it’s about a group of people investigating a haunted house, we can’t ignore the fact that the characters question their experiences in the house, their mental states, and whether at least one is going mad.

- In The Shining (1977) by Stephen King, filmed in 1980 (dir. Stanley Kubrick), Jack Torrance’s unbalanced mental state—brought about by his frustration over writer’s block, his alcoholism, and the weird phenomena at the Overlook Hotel (again, shades of haunted house!)—leads to unpredictability and extreme violence toward his wife and young son, Danny.

- Misery (1987) also by Stephen King, filmed in 1990 (dir. Rob Reiner), features Annie, who rescues her favourite author, Paul, from a car accident but quickly shifts from helpful to harmful. Her unpredictability and extremes (here’s a woman who refuses to swear but who hobbles Paul with a sledgehammer so he won’t escape) become the locus of all the terror because neither he nor the reader/viewer can predict how she will act.

(Kathy Bates in Misery; source)

- Though Silence of the Lambs (1988) by Thomas Harris, filmed in 1991 (dir. Jonathan Demme) is a crime thriller about the FBI trying to find a serial killer, agent Clarice Starling matching wits with cannibal Dr Hannibal Lecter is, at its core, pure psychological horror. We have no idea whether he can be trusted and whether he’s manipulating Clarice to try to escape by getting inside her head.

- More recently, The Last House on Needless Street (2021) by Catriona Ward (which was snapped up by Andy Serkis’s production company that same year), is about the effect that abuse can have on a person’s psyche and how memory plays tricks on us. The use of multiple points of view, including a cat and a child, means that readers question who to trust and what’s really happening.

The importance of setting

Because of the connections between psychology and certain places, the world-building of psychological horror often depends on setting-related tropes that readers and viewers recognise. In psychological horror, the source of fear is due to what’s going on inside the character, but the use of particular places and related images/items has cemented a connection between mental health and horror. These can be used to ramp-up a reader’s or viewer’s reaction.

The setting most obviously connected to psychological horror is the mental institution or hospital. From the crowds at Bethlem to videos of people exploring abandoned mental hospitals, there is an audience curious about these places—and the people who were in them—likely because of a fear that we could one day find ourselves there as patients. These stories are populated with elements that can create variable levels of disturbance in a reader or viewer, from mysterious corridors with flickering lights, to dangerous-looking medical instruments, to masks, gloves, and straitjackets. There is no end of films set in mental institutions or asylums, though they run the gamut from full-on slasher to supernatural, so sometimes the horror is due to mysterious entities (ghosts, the spirits of murderers, etc.) rather than the intricacies of psychological illness.

(Photo by Nathan Wright on Unsplash)

Why this is might have to do with the attention on mental health issues and treatment: maybe we feel so “on the ball†now about it that psychological illness isn’t as scary in literature and films, so the creators feel the need to ramp up the horror with supernatural catalysts.

One trope that pops up often is the protagonist who goes to the institution, often as part of an investigation, only to discover that they are actually a patient, feeding on a common fear of losing one’s faculties and being institutionalised. In Dennis Lehane’s 2003 novel Shutter Island (filmed in 2010, dir. Martin Scorsese), a U.S. Marshall investigating the disappearance of a missing patient at an island-based institution for the criminally insane comes to discover that he is a patient there being led through his delusions to see whether he can maintain the truth of his crime or will be lobotomised. This is a version of an unreliable narrator, but one in which the unreliability is based on the side effects of trauma, PTSD, or other mental illnesses such as schizophrenia. Sometimes the protagonist is the unreliable one and sometimes it’s another character, which can increase the questions about what’s real and what’s not.

Internal vs external

As noted earlier, people in the past often believed that someone exhibiting certain behaviours was possessed by demons or being punished for sins, so it’s not a stretch to see how in this subgenre characters might believe that what they hear inside their head is coming directly from a deity or paranormal being, whether good or evil. Faith can be a heady theme when used in psychological horror, especially with Western/Christian religious buildings as settings (see Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1510) and other religious paintings of the mediaeval and Renaissance periods for some ideas of what the faithful believed), as well as iconography from stained-glass windows to religious vestments and ritual objects.

(Photo by Camila Quintero Franco on Unsplash)

We see this crossover of psychological horror with religious horror in Consecration (dir. Christopher Smith, 2023), a convent-set film that combines past abuse, mental health issues, and the mysteries and secrets of the church. Faith is a major theme in this type of psychological horror because of the questions asked: Is believing in something that cannot be proven a symptom of insanity? Does the character deserve the horrible punishment being committed, and does that mean that a reader/viewer can suffer the same fate? And, if you don’t believe in [insert whatever entity], can it harm you or, is it truly all in your head?

Finally, we have the most familiar setting: home. We spend most of our time at home, which is supposed to be comfortable and safe. Unfortunately, family dynamics are sometimes the source of mental illnesses, so this can be a fraught setting (see Brian De Palma’s 1976 film version of Stephen King’s 1974 novel Carrie for a good example). The house as setting will contain items specific to your character, but some elements that pop up in this subgenre include “hidden spaces†such as closets, basements, and attics, and a threat that is already in the house (a mirror of the idea of our own minds as a threat).

An urban legend from the 1960s (based on the 1940 murder of a babysitter) about a man repeatedly phoning a teenage girl babysitting children who are asleep upstairs and threatening her (telling her to check on the children or otherwise stalking her), called “The Babysitter and the Man Upstairsâ€, is the source material for several films in which this or a similar set of calls terrorise a girl who discovers the man is inside the house. In When a Stranger Calls (1979, dir. Fred Walton; remade in 2006, dir. Simon West), this formula is closely followed. In Black Christmas (1974, dir. Bob Clark; loosely remade in 2006 as Black X-mas, dir. Glen Morgan; and again loosely remade in 2019, dir. Sophia Takal) the threat is in a sorority house, with each iteration building on the original trope. In the first, the phone calls come from the killer hiding in the attic; the second is more of a teenage slasher film in which we learn the story of the killer’s abusive childhood, and his childhood house—turned into a sorority house—is where he returns to terrorise the students; and the third iteration, also a slasher film, at least expands on its exploration of psychological issues with a university-student protagonist who is dealing with PTSD, though now terrorising phone calls have evolved to text messages (timely due to texting and social media in general leading to many mental health issues in young people).

A final word

Human beings are messy, yes, but fascinating. In psychological horror, the monsters are often manifestations of fears that readers themselves have. So, as we experience the story, we identify with the protagonist, and that connection creates a heightened feeling of unease and even terror: we’re not only afraid for the character but also of ourselves because we recognise the human behaviours on display.

It’s a subgenre that can keep on evolving as we learn more about how our brains work (as contrasted to stories about supernatural beings, such as vampires, which are usually inspired by or work to subvert the known tropes, themselves based on familiar folk tales).

As humans we relate to other humans, and in psychological horror, the depths of human behaviour and mental somersaults are laid bare. We must ask ourselves how close we are to tipping over the edge into paranoia and even madness. And that’s what makes psychological horror so scary: we know vampires and ghosts don’t exist, but we do, and we’re the scariest monsters there are.