We’ve implemented some new protocols around sending us messages via this website. Please email website “at” britishfantasysociety “dot” org for any issues.

For all things fantasy, horror, and speculative fiction

-

Announcement:

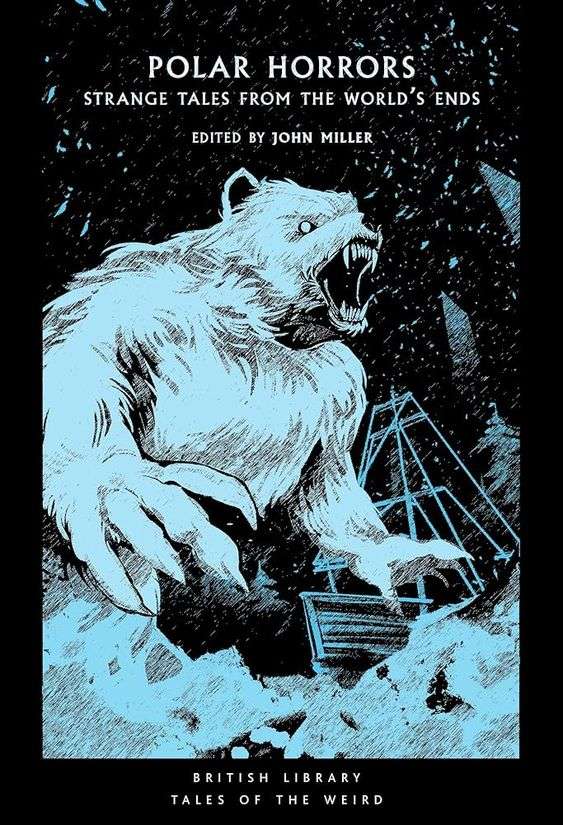

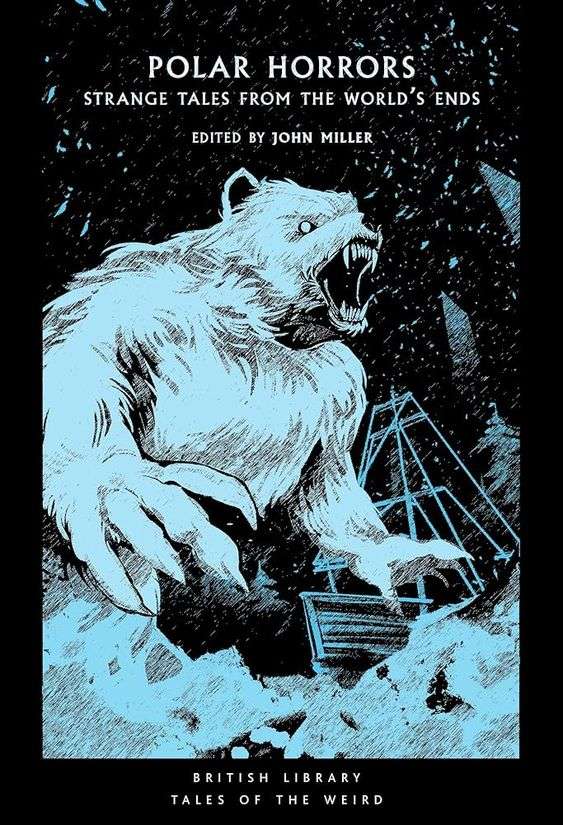

Polar Horrors

POLAR HORRORS: Strange Tales From the World’s Ends, edited by John Miller

British Library Press, p/b, £9.99

Reviewed by Pauline Morgan

It would be fair to say that the majority of authors whose stories are included in this book never had the opportunity to visit the places where they are set and had to rely on the written descriptions of others and their own imaginations. It is also unlikely that the readers, especially at the time of the first publication, had experienced the conditions described. The stories in this volume are set either within or very close to the polar circles, and all feature extremes of weather. They are divided into two sections, with six stories set in the north and six in the south.

‘The Surpassing Adventures Of Allan Gordon’ by James Hogg (1837) is a ‘Robinson Crusoe’ story but set in the Arctic. Allan Gordon is the sole survivor of the wreck of a whaling ship trapped by ice. Whereas the rest of the crew died in the accident, Gordon is left alone but with plenty of stores in the ship’s hold. His companion is a polar bear cub, Nancy, which he raises after her mother dies. His island is a giant iceberg. It is a fanciful story but is one of isolation, endurance and innovation. In ‘The Moonstone Mass’ by Harriet Prescott Spofford (1868), the narrator is part of an expedition searching for the North West Passage, a sea route north of Canada which was believed to link the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. When the ship is trapped in the ice, he and a companion are sent off westward to find help. He ends up alone and on a floe, drifting with the current.

‘The Captain Of The “Polstar”’ by Arthur Conan Doyle (1883) concerns another whaling ship, though this time it is only in danger of being stuck in the ice. This may or may not have supernatural elements as Captain Craigie, after several days of worrying behaviour, disappears onto the ice in pursuit of the phantom he has seen. Although again, we have a man alone on the ice, this time, he is the one being searched for by the narrator and the rest of the crew.

Liberties have been taken as to where the Polar Regions are, as in ‘Skule Skerry’ by John Buchan (1928). Skule Skerry is an uninhabited island to the west of the Orkneys. The story is narrated by ornithologist Anthony Hurrell, who is convinced that this will be the best place to observe bird migration. The locals on the mainland try to dissuade him, but he is determined and sets up camp. It is cold and very windy, and the local stories scare him. Whether there is anything supernatural or not is irrelevant, as this is a darkly atmospheric story.

‘The Third Interne’, by Idwal Jones (1938), is set in a prison at the edge of the Arctic Circle. Dr Alexis Garshin is there as an inspector, but while the prison director is away, a young man introduces himself and tell Garshin a story of bizarre experiments that have been carried out there. The place is bleak and isolated, and there is a blizzard raging outside. Though the writer is very specific as to the location, it is a story that could be set in any place with the same conditions.

Perhaps the most interesting story in the whole volume is ‘Iqsinaqtutalik Piqtuq: The Haunted Blizzard’ by Aviaq Johnston (2019). Not only is it a very recent story but it mixes the modern with legend. Johnston is an Inuk writer who brings authenticity to her stories. This one starts with the children being sent home from school as a blizzard approaches. The narrator is told that there are bad things in the storm. He reaches home but is convinced he has been followed. This is true horror.

Many of the stories in the south-polar half of the anthology were influenced by the expeditions to reach the South Pole. ‘A Secret Of The South Pole’ by Hamilton Drummond (1901). Although set in the tropics, this describes the finding of a derelict ship by three men adrift in the Pacific in a small boat. The derelict appears to be about three hundred years old and has been encased in ice. ‘In Amundsen’s Tent’ by John Martin Leahy (1928), the expedition actually reaches the South Pole, though it is not the first to do so. On arrival, the team find a tent and, when looking inside, discovers a severed head and a journal. This relates to the story of the previous expedition and how they found a tent with a Norwegian flag on it, identifying it as Amundsen’s. Two look inside and declare that whatever is inside is a horror. The rest of the journal has a Lovecraftian touch to it. ‘Bride Of The Antarctic’ by Mordred Weir (1939) displays some similarities with Leahy’s story in that an expedition to the Antarctic set up in the same place as a previous one, and where all except two had died, one of them being the wife of the expedition leader. Essentially, this is a ghost story.

A number of stories set in the Antarctic postulate some kind of hidden valley where there is a kind of Eden. ‘Creatures Of The Light’ by Sophie Wenzel Ellis (1930) is about the creation of such an Eden. Dr Mundson has developed a Life Ray and is using it to accelerate evolution and create the next stage in human evolution. ‘Ghost’ by Henry Kuttner (1943) involves technology. The Integration Station in the Antarctic is basically a huge computer server. The problem is that it is haunted, not in the classic way with the spirit of a dead person, but with the emotions of the original operator who killed himself. Technology has created the ghost, psychiatry has to find the solution.

‘The Polar Vortex’ by Malcolm M. Ferguson (1946) is another experiment at the South Pole. An eccentric multi-millionaire persuades his unsuspecting subject to become the caretaker of his observatory for a month, alone except for the stars. Isolated, he loses track of time.

Many of these stories are explorations of the effects of isolation on the human mind. It is worth remembering that when they were written, there was no instantaneous communication that would alleviate many of these situations if they were to occur today. They are a reminder of the times in which they were written. It is also noticeable that although some of the stories are written by women, they do not, with one exception, feature as characters in the tales.

Explore the blog:

Blog categories:

Latest Posts:

Tags:

#featured (56) #science fiction (25) Book Review (264) events (44) Fantasy (231) Graphic Novel (13) horror (136) Members (62) Orbit Books (48) profile (43) Romance (17) Science Fiction (50) short stories (28) Titan Books (52) TV Review (15)

All reviews

Latest Reviews:

- THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND by William Hope Hodgson

- Monstrum by Lottie Mills

- Mood Swings by Dave Jeffery

- Yoke of Stars by R.B. Lemberg

- Hera by Jennifer Saint

- The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness

- RETURN OF THE DWARVES By Markus Heitz

- Delicious in Dungeon

- Toxxic by Jane Hennigan

- THIS ISLAND EARTH: 8 FEATURES FROM THE DRIVE-IN By Dale Bailey

Review tags:

#featured (2) Action (4) Adventure (4) Book Review (28) Fantasy (18) Featured (2) Feminist (2) Gothic Horror (3) Horror (14) Magic (3) Orbit Books (3) Romance (6) Science Fiction (5) Swords and Sorcery (2) Titan Books (7)