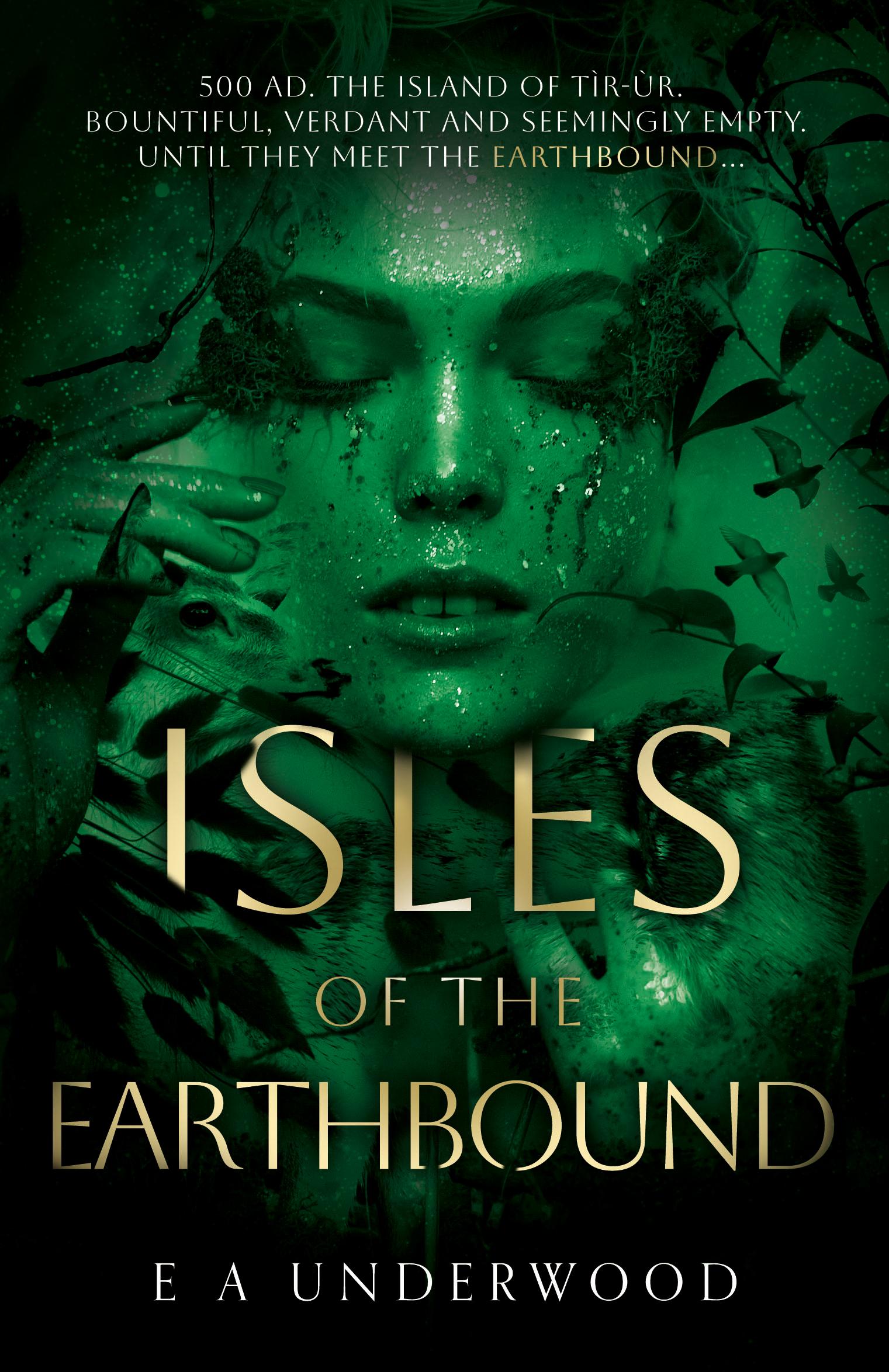

With her new book Isles of the Earthbound taking inspiration from British and Irish myth, EA Underwood believes there is still plenty of juice in mythology (outside of the Classics!) for fantasy writers.

Recently there has been an almost overwhelming tidal wave of retellings of Classical myths from a feminist viewpoint. The appeal of these stories is nothing new. One of the first I ever read was C S Lewis’s Till We Have Faces. As a young teenager I was captivated by this book. I confess it got me hooked. Since then many outstanding authors have turned their hands to the genre. With great relish I devoured Ursula K Le Guin’s Lavinia, Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, and more recently the works of Madeline Miller and Pat Barker.

There is no doubt that retellings can make great reads and provide a fresh perspective on ancient stories. But I can’t help feeling that eventually you can have a surfeit of a good thing. And perhaps we need some surprises—after all, we know that Circe will turn Odysseus’ men into pigs and Perseus will inevitably chop Medusa’s head off.Â

I find myself turning to stories based more on British and Irish mythology, for we have such a vast under-utilised resource closer to home. There have been numerous retellings of the Arthurian myths, but we already know all about Merlin and Mordred, Guinevere and Morgause. With much of the history of our islands we do not have the luxury of a complete plot line and some of the most fascinating modern creations are not the retellings but those that take the glimmer of an idea and run with it to improvise new stories, worlds and magic systems.

In this process mythology can become a catalyst: a trigger, something that sparks a reaction into progress, that creates a new and different substance. It can be a folk tale or a song, a fragment of oral history, an artefact, a location or even just the name of a character that forms the initial thread of a narrative.

From the Mabinogion to the Wild Hunt

This process itself is nothing new. Tolkien of course used mythologies from all over Northern Europe for inspiration in the creation of Middle Earth. Alan Garner used the tale of Blodeuwedd from the Mabinogion to inspire The Owl Service. He wove together strands from English, Irish and Welsh folklore with medieval legends of unicorns and virgins to create the mythology for Elidor.

There are legends of the Wild Hunt all across Europe from Scandinavia to Italy and so many fantasy novels in which this trope appears, from Tolkien and Garner, through Susan Cooper and onwards. Perhaps the motif could seem a little overused, but we have recently had exciting new interpretations of the Hunt and its dreadful but charismatic leader. In her recent novel Song of the Huntress, as in certain Germanic legends, Lucy Holland has given us a female leader of the Wild Hunt in Herla, one of Boudicca’s warriors who makes a pact with the king of the Otherworld in a bid to save her land from the Roman invaders. Holland also takes the little we know of King Ine and Queen Æthelburg from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and puts flesh on their ancient bones. In Zoe Gilbert’s unique and wonderfully weird Mischief Acts, Herne the Hunter is a trickster spirit and leader of the Wild Hunt who, in many different incarnations, lasts throughout the ages into modern times and into the future.

In Cwen, for me one of the outstanding books of 2021, Alice Albinia reached deep into ancient texts for inspiration. In the seventh century Irish poem The Legend of Bran, in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The Life of Merlin and in numerous other original sources she found legends of islands where women ruled and used them as the basis for her fictional archipelago. The eponymous Cwen herself is an eternal spirit, the ultimate symbol of feminine power, and a masterful distillation of the many versions of the crone legend.

Sometimes there is the widest scope for improvisation in time periods and locations for which we have the least information. In Dark Earth, Rebecca Stott has delved into the literary desert that is post-Roman Britain. She describes this as “the darkest corner of the Dark Agesâ€. Inspired by an Anglo-Saxon woman’s brooch found amidst the remains of a Roman bathhouse, and aided by a network of archaeological experts she has conjured up post-Roman Londinium as the setting for a magical and evocative story.

Brewing Up New Magical Concoctions

In my novel Isles of the Earthbound I found the catalyst for the creation of a new story in legends of mythical lands such as Hy Brasil, Avalon and TÃr na nÓg. These realms of beauty and abundance are inhabited by mysterious faerie folk who may or may not be hostile to human visitors. It came to me that, given our record with regard to colonisation, it might actually be us who were the danger. If we had discovered such an earthly paradise, I considered it highly likely that we would have tried to exploit its resources and inhabitants and wreck its ecosystem—just like we have elsewhere.

When I was stuck on a plot point in the novel, I turned to Irish legend in the form of the Leabhar Buidhe Leacáin in which the High King Muichertach mac Erca becomes enamoured of a beautiful girl he meets out hunting. The mysterious woman gives her name as SÃn or ‘storm’. SÃn uses her powers to ensnare the king but comes to genuinely love him, even though her original plan was to gain revenge for the king’s destruction of her family. This legend influences the outcome for both my main protagonist and also for the fate of her mother.Â

I myself carry Scots, Irish, English and French blood, so I feel a smug justification for my ransacking of various mythologies for inspiration. To some it might seem a little disrespectful and in some ways profligate to cherry pick in this manner, plucking cultural elements at random, and there has been too much cringeworthy commercial exploitation of ‘Celtic’ mythology in popular culture. Yet we are so lucky to have these wonderful resources which deserve to be used, with careful acknowledgement, to create new stories relevant to current issues. We have all this succulent fruit—let’s use and celebrate it. Let’s throw it in the cauldron and use it to brew up new magical concoctions.Â

Isles of the Earthbound by EA Underwood is now available through The Book Guild