We’ve implemented some new protocols around sending us messages via this website. Please email website “at” britishfantasysociety “dot” org for any issues.

For all things fantasy, horror, and speculative fiction

-

Announcement:

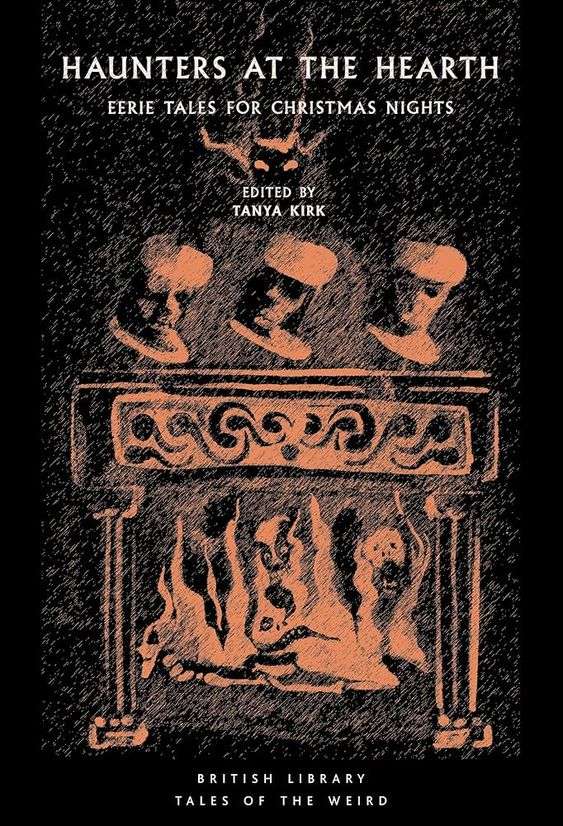

Haunters at the Hearth

HAUNTERS AT THE HEARTH: Eerie Tales For Christmas Nights, edited by Tanya Kirk

British Library Press, pb, £9.99

Reviewed by Pauline Morgan

Traditionally, Christmas is a time when ghosts make themselves evident. Perhaps it is the idea from before, all pervading electric lights when candles and firelight were the only things to keep the shadows at bay. Then, the idea of groups scaring each other with tall tales was a way of preventing any real ghosts from intruding. Ghost stories have been written or told for centuries, and this anthology includes stories written in or around Christmas and span a period of over a century.

There is a similarity between ‘The Phantom Coach’ by Amelia B. Edwards (1864) and ‘Dr. Browning’s Bus’ by E. S. Knights (1933) but they utilize the transport common at the time they were written. The use of transport to carry the dead into the next life is a well-utilized theme – both use it here. Both stories are set in winter during snowy weather. The difference is that the former recapitulates an old accident, and the narrator is trying to get back to his wife after having become lost, while the former is a doctor trying to reach a dying patient.

Relatively few use the time-honoured situation of telling ghost stories beside a fire.

In ‘Jerry Bundler’ by W. W. Jacobs ((1897), the characters decide to play a practical joke on the sceptical member of their group by recreating the apparent resident ghost at their inn. In a similar vein, in ‘The Mirror In Room 22’ by James Hadley Chase (1944), the story is designed to have an effect on one particular member of the company. In both cases, the events take place just before Christmas.

December, in the run-up to Christmas, used to be a time of winter storms when snow and ice could be expected. In ‘Oberon Road’ by A. M. Burrage (1924), Michael Cubitt breaks a habit of a lifetime and speaks with a man on a train who directs him up a ‘shortcut’, which has the effect of changing his approach to his life. ‘The Last Laugh’ by D. H. Lawrence (1925) has surreal elements, such as when three people go home through the snow, followed by laughter from an unseen source, which intensifies from curiosity to fear. Winter conditions influence the events in ‘At The Chalet Lartrec’ by Winston Graham (1947) when the narrator looks for somewhere to stay the night when the mountain roads become too treacherous to continue. He is directed to Chalet Lartrec, a hotel which is closed for the winter season. ‘Account Rendered’ by W. F. Harvey (1951) is set on 17th December and involves a strange request by a man who wants to be given a general anaesthetic at a specific time on that day.

Winter weather also plays a part in ‘Deadman’s Corner’ by George Denby (1963), where a watchman at a roadwork is confronted by a man who tells him about the local ghosts and how they cannot move on until someone agrees to take their place and haunt that stretch of road. ‘Don’t Tell Cissie’ by Celia Fremlin (1974) tells of two longtime friends who investigate the alleged ghost in one of their cottages during winter. They don’t want Cissie to know as she will want to come, and she is very clumsy and always manages to spoil things.

‘The Earlier Service’ by Margaret Irwin (1935) culminates at the time of December’s full moon. Jane Lacey, the vicar’s daughter, is reluctant to attend services. At her Confirmation, she sees figures from the past around the altar, which makes her even more reluctant to attend the early service on the full moon before Christmas.

Several stories involve customs in the lead-up to Christmas. In ‘The Wild Wood’ by Mildred Clingerman (1957) is the hunt for a Christmas tree. In the store, to which the family returns every year, Margaret is uneasy, having visions about the creepy store owner. Pantomimes are a tradition for Christmas time, and in ‘Whittington’s Cat’ by Eleanor Smith (1934), the protagonist, Martin, develops an obsession with them, going every night. His excuse is that he is doing research for a book until the man-sized cat follows him home. Martin hates cats.

Carol singers are the feature of ‘The Waits’ by L. P. Hartley (1961). Mr. Marriner chased them away until Christmas Eve. Now, when he sends his children to give them their reward, they refuse to accept it, saying he has to give them what he owes. It is also Christmas Eve when the narrator in ‘The Cheery Soul’ by Elizabeth Bowen (1942) arrives at the house where she has been offered refuge. Her work is part of the war effort but her landlady needs her room for relatives over the festive period. When she arrives, the house is empty except for an old woman who seems senile. The cook is absent as well but has left mysterious notes in unexpected places.

It is also 24th December when in ‘Christmas Honeymoon’ by Howard Spring (1939), the newly married couple on a walking honeymoon in Cornwall find a village where they are hoping to stay the night. It is deserted but appears to have only just been vacated. They liken the mystery to that of the Mary Celeste. Also, on Christmas Eve, ‘Bone To His Bone’ by E. G. Swain (1912) spirit activity leads a vicar to find a bone in the garden, which he reinters in holy ground.

Equally important for the season is New Year’s Eve. ‘Between Sunset And Moonrise’ By R. H. Malden (1943), another vicar is visiting a distant parishioner in Norfolk at the turn of the year and has a very frightening experience in one of the narrow droves that are common in the area when threatening figures appear out of a sudden fog.

While most of these stories are not actually set at Christmas, they are of the kind that would be told on dark nights around open fires. Like all the volumes in this series, the tales reflect the society in which the author was writing.

Explore the blog:

Blog categories:

Latest Posts:

Tags:

#featured (56) #science fiction (25) Book Review (264) events (44) Fantasy (231) Graphic Novel (13) horror (136) Members (62) Orbit Books (48) profile (43) Romance (17) Science Fiction (50) short stories (28) Titan Books (52) TV Review (15)

All reviews

Latest Reviews:

- THE HOUSE ON THE BORDERLAND by William Hope Hodgson

- Monstrum by Lottie Mills

- Mood Swings by Dave Jeffery

- Yoke of Stars by R.B. Lemberg

- Hera by Jennifer Saint

- The Black Bird Oracle by Deborah Harkness

- RETURN OF THE DWARVES By Markus Heitz

- Delicious in Dungeon

- Toxxic by Jane Hennigan

- THIS ISLAND EARTH: 8 FEATURES FROM THE DRIVE-IN By Dale Bailey

Review tags:

#featured (2) Action (4) Adventure (4) Book Review (28) Fantasy (18) Featured (2) Feminist (2) Gothic Horror (3) Horror (14) Magic (3) Orbit Books (3) Romance (6) Science Fiction (5) Swords and Sorcery (2) Titan Books (7)