Folk horror writer and poet Stephanie Ellis asks where all the older women are in fiction—especially in horror, where the evil crone stereotype dominates, and especially in folk horror, which centres so much on fertility.

Funny how you don’t think about older women in fiction, or even in life in general – until you become one. Prior to that, you are living your younger life, ignoring pretty much everything else and your only contact with older folk tends to be parents and grandparents. And much as you love them, again there is this slightly dismissive approach to them because they are ‘old’ and ‘don’t get it’. Lives are so busy you pay little attention to those moving more slowly around you. Age is dismissed and fought against, particularly for women and particularly in some Western societies.

Oh, how this all comes back to bite you as you take your place on these final rungs of the ladder and look to see yourself in society, on television, in fiction … where are you and your peers now? How are we represented?

Hmm, not so favourably it seems. As an older female author, I came to writing late, starting properly around the age of fifty when I completed a short story writing course with Writers News and being told I could write but my style and content were not necessarily for the usual markets, ie People’s Friend and various women’s magazines. Slightly(!) disgruntled, I flicked through the writing magazine’s pages and spotted a call for a potato-themed horror anthology. I had never written horror before so really had no clue but I did come up with a dark story: Death is not a Potato. Rejected yes, but it led to further submissions which were accepted for other anthologies and the years began to tick by. So far, so good. Sort of. In those earlier days, I noticed the TOCs for anthologies were often male dominated both as authors and editors. I realised that horror in a way was very much stuck in the past, that the horror these editors expected seemed to be weighted against women. Again, times changed. Women began to take on roles as editors, started up presses, appeared in a variety of aspects within the genre and became accepted. I stepped into the editor role at Horror Tree’s Trembling with Fear zine and helped build that up over a five-year period before handing on to Lauren McMenemy. Horror Tree has always been one of the most welcoming places for women. Your sex or gender does not matter, it is what you do that counts – and that has improved considerably across the genre. Sometimes I think there is still a way to go, but it’s getting there.

But when I started to do the online thing, signing up to social media platforms, following people, that was when it hit me – I did not see anyone like myself. The women all looked younger, more glamorous and I suddenly felt adrift. I looked again and felt I did not belong. So I put a call out, were there other 50+ women writing? They responded, coming out of hiding, and all felt pretty much as I did, that we were not truly part of the writing world. And whenever the words ‘new writer’ were mentioned, it invariably meant a younger writer. A plea to the industry: new does not mean young!

The final nail in the coffin was hammered home at a recent writers’ group meeting when we had a zoom call with a young female agent from a literary agency in London and we directly queried the perceived ageism against women. It was admitted. Yes, there are some older female writers, but they are more tokens and yes, they could do, should do better. And quite often I discover that those who are older have actually started at a younger age.

The odds seem to be stacked against us based on appearance and not on talent. But I live in hope and still continue to query agents. I’ve a few good years and certainly a number of books left in me! I will not give up. Sixty is still relatively young in the grand scheme of things. I would love to see more of us openly participating at conventions, at events online, actively raising our profile so that to see an unfiltered, genuine woman over a certain age becomes accepted and respected. This has been my experience and also my perceptions. Others may find differently.

Horror sees women as hags and crones

Now to the content of horror fiction. How is the older woman represented? Stereotypically, methinks.

If there is an old(er) woman in film or literature, she is often represented as a hag or crone. Someone horrible to look at and usually with a temperament to match. How many of us know the original version of Goldilocks and the Three Bears? The Story of the Three Bears was written by Robert Southey and the protagonist was not a pretty little girl, but an ‘impudent, bad old Woman’ who is ‘ugly, dirty’. Grimm has old wise women in his collection but still the idea of this older evil creature permeates, as in The Old Woman in the Forest and Hansel and Gretel.

As I read and explored the folk horror subgenre, one in which I write, I soon perceived the relative absence of the older woman. They appear very much on the sidelines, partly because an overarching theme is the theme of fertility, whether of the land or of the woman. The Maiden holds promise, the Mother carries the much-needed children. The third age of woman, the Crone has gone beyond those stages, is now useless in reproductive terms and therefore not as important and can be cast aside. In my essay “Non-normativity in Female-Centred Folk Horror Tradition†(Future Folk Horror, Contemporary Anxieties and Possible Futures ed. Simon Bacon), I looked hard for older women in the stories and found they were “tied to earlier patriarchal conceptions of their symbolic role as a crone in such narratives.†An example being the old woman who summons the ancient creature Moder towards the end of Adam Nevill’s The Ritual and also of the ghost of the witch in Thomas Olde Heuvelt’s Hex. The only positive depiction of an older woman when I was studying literature for this article was in James Cooper’s The Man in the Field, where the widow Mother Tanner is treated with disapproval and suspicion because of her independent nature and determination to seek the truth as to the nature of the cult to which she belongs.

And I know I’m not the only person to have seen the stereotyping of women, a form of ‘hagsploitation’ as written about in Clarisse Loughrey’s article “Have horror movies made a monster out of the older woman?†in The Independentonline. She quotes Meryl Streep who ‘noted that older woman were rarely written as anything other than “gorgons or dragons or in some way grotesqueâ€. This article finishes with this:

‘In 2017, psychologist Renee Engeln coined the term “beauty sick†to reference what she saw a society-wide mental illness that fixates on women’s appearances. The stalkers, witches and cannibals that take bloody measures to seek their own self-preservation serve as living incarnations of this … But it also acknowledges that it’s society that has so rigorously preprogrammed women to react in this way, making them feel like every passing year renders them a little more invisible to the world.’

Demi Moore’s latest film, The Substance, is one which feeds into this aspect. The desperation of the older woman to look young, the dismissal of the older by the younger, the misogyny of the men in power. The message is blunt. Acceptance of the older woman will only come when society’s attitudes have changed, when women stop using filters, stop panicking at grey hairs, stop the botox, the nips and tucks.

(Pictured: Demi Moore in The Substance; source)

To be older is not to be decrepit. We can still exercise, remain healthy, enjoy life but as ourselves and not as some fake manufactured version. Readjustment of perception of age should focus on the positive, the wisdom and experience of older women, the knowledge they hold. Isn’t that ultimately more valuable than the flawless complexion?

A woman’s changing body is pure horror fodder!

Nor is a woman’s life defined by external appearance, but also the changes within. My own writing journey has been one taken in parallel with my changing body, going through perimenopause, relatively mild at first until it became horrific in the last few years – the worst being the insomnia on top of so much else going on. Now postmenopausal by two years, I am still suffering a number of symptoms, and speaking to other women of my age or going through that transient stage, I realised that I do not see this represented in fiction either. Certainly not in horror, although it is being picked up on a little. There was an anthology call a couple of years back for menopausal horror which I submitted to. My story was rejected because they had already accepted as similar-themed one but they loved my ‘sensory detail’. Yes, I was living the dream! But apart from this and I think another menopause-themed anthology, I didn’t see a woman suffering any such symptoms as they traverse the pages of their story in the books I picked up. Or in TV or film. They don’t endure hot flushes and I mean the all-consuming volcanic monster that erupts and which destroys all focus as you deal with it, they don’t suffer insomnia, they don’t have brain fog, they don’t have digestive issues. These are all aspects of our biology which we have to deal with, and sometimes very visibly. Yet this is generally invisible in fiction. But the sheer change a woman goes through must have some impact on the older female MC. Perhaps they are all on HRT (if available)?

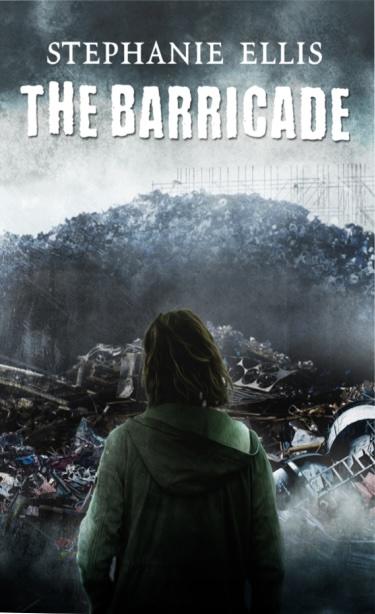

So I wrote a book. My latest novel, The Barricade, is a postapocalyptic/scifi/horror mashup and my main character is menopausal and her symptoms crop up at inconvenient times, affect how she is perceived, how she sometimes responds. It does not weaken her character in any respect but shows her truer to the nature of her biology. Women have to co-exist with their reproductive system in a way the male does not. We adapt and get on with things, that is our strength, but to sweep it all under the carpet does no favours to those who come after, who don’t realise how much a biological change can affect their days in such an intense manner. Forewarned is forearmed and all that – I’m still very much at the ‘I was never told that’ stage of my life and just wish I’d known what to expect sooner. I do not want to see older women shown as ‘weaker’ because of this aspect of their lives, but I do want to see its portrayal so that it is normalised.

Let women be women, let them not be defined by society, by the male gaze, by each other, but by themselves.