Allen Ashley heads to Greenwich, London, to review the in-person exhibition “Pirates” at the National Maritime Museum. All photos included were taken by Allen on-site.

Pirates are a common staple of fantasy and adventure fiction, sometimes glamoured up with extra talents such as living out in space, being ghosts, having apparent superpowers and the like.

Though not as strictly fantastic in the way of, say, elves or selkies, pirates pop up frequently within our genre. With that in mind, many of you may be interested in attending the exhibition Pirates at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London before it closes on 4 January 2026. It’s certainly well worth the trip.

For myself, I have a slightly troublesome relationship with pirates. Sure, I can still tune in to the childish excitement and abandon that they represent. Ask any primary school age kid to draw a pirate or dress up or act like one and you are onto a winner. But I was teaching a session at my advanced adult SFF group Clockhouse London Writers a few months ago and one of the submission markets was focused on pirates; and I had to admit to having some reservations celebrating what one could perhaps cast as a group of thieving, murderous villains… who probably didn’t smell that clean, either!

Here Be Treasure

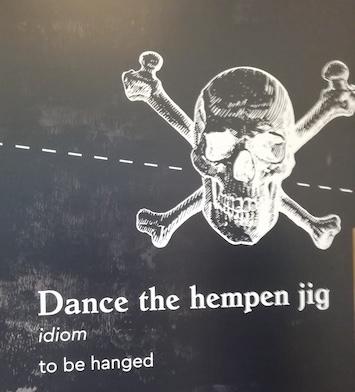

This exhibition seeks to deal with this dichotomy—the abiding cultural image of pirates versus their real lives. The opening salvo, taking up probably one-third of the hall space, is the most successful part of the show and covers pirates in popular culture.

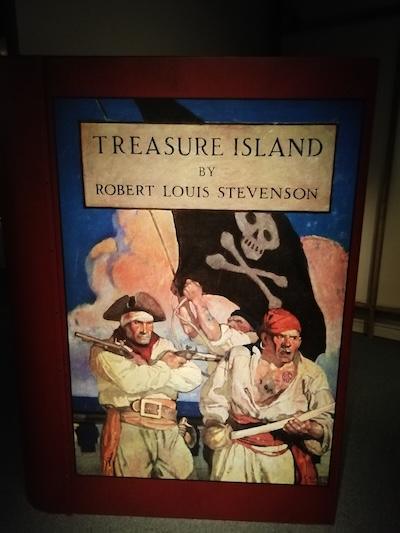

We begin with the defining original text that set the template for our shared vision of pirates: Treasure Island (published 1883) by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-94). This has the lot—a young hero cabin boy Jim Hawkins and his journey from innocence towards manhood; secret treasure and maps and desert islands; cut-throat pirates (notably wooden-legged cook Long John Silver); a talking parrot in Captain Flint; prophecy (the “black spot” message meaning you are doomed to die); adventure on the high seas in a galleon… We have a few editions on display here, including one illustrated by Mervyn Peake (1949) and a colourful edition for children illustrated by Ralph Steadman (1985).

There’s also a well-weathered 17th Century pistol in iron, brass and wood of the sort Jim used to defend himself against the murderous Israel Hands, along with a lovely diorama of the ship Hispaniola lying off the coast of Treasure Island.

Just pre-dating Stevenson’s work, we have posters and publicity for the 1879 Gilbert and Sullivan operetta The Pirates of Penzance – piracy here played for laughs down in Cornwall and including the timeless ditty A Policeman’s Lot.

The next major pirate in fiction was Captain Hook, the menacing but vulnerable baddie from Peter Pan by J. M. Barrie (first performed 1904). On screen, pirate films have been around since the early twentieth century and proved particularly popular during the 1950s and 60s—from Annie of the Indies 1951 to Carry on Jack 1964, with later revivals including Robin Williams in Hook 1991 and, of course, the supernaturally tinged, hugely successful Hollywood franchise that began with Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl in 2003. The museum has relevant film clips and costumes on display here.

One of the treasures of this exhibition is a case devoted to the British TV cartoon character, the loveable but somewhat inept pirate “Captain Pugwash” (1950s-1975). Author and animator John Ryan used a simple technique of tabs and pins which enabled him to move a character’s arms, legs, eyes or mouth. It’s quite a contrast from the high-tech CGI and AI at work today—it’s almost something one could replicate at home. These black and white cardboard cut-outs are authentic and nostalgic.

Fashion and Other Issues

Pirates have also become popular through various computer games such as Assassin’s Creed. Then there’s the fashion influence, notably that centred around the New Romantic movement of the early 1980s and the furniture and fashion designs of Vivienne Westwood, as featured on the covers of The Face and Vogue in 1981 and as exemplified by the stage outfits of Adam and the Ants, Anabella of Bow Wow Wow and, later, those of Duran Duran.

Playmobil is the German company that forced Lego to seriously up its game. Here we have a rather troubling Playmobil pirate ship which originally featured a Black sailor wearing a slave collar—this as recently as 2011. What were they thinking?

On a more positive note, many folks will recognise the artistic talents of Frank Humphris and his action-packed images of pirates produced for Ladybird Books in the early 1970s.

The Golden Age?

We are now invited to learn more about real pirates. There are displays on the likes of Captain William Kidd (c1645-1701), Edward Teach AKA Blackbeard (c1680-1718), and the female pirates Anne Bonny (1698-1782) and Mary Read (c1695-1721). The “Golden Age of Piracy”, if one dares call it that, lasted from about 1680 to 1722 and these were some of the major players. Pirate life on board ship was not all drinking and carousing—rising at sunrise, eating a biscuit and a strip of preserved meat and having a host of jobs to complete. Boozing and gambling were often outlawed on ship; discipline and obedience being key to success, as in any criminal gang.

Pirates didn’t just steal gold, silver and coins as certain films would have you believe. Spoils were anything they could trade—spices such as cloves and peppercorns, dyes such as indigo pigment, silks, coffee beans, food in general. Sometimes people would be captured and held for ransom or selling.

Something I learned: On display we have coins from the era called “8-reales”, “4-reales”” and “2-realses” – silver, made in Mexico c1620s. Eight-reales or Spanish dollars “are considered to be the world’s first global currency”. The coins were “physically split to make smaller denominations, earning them the name ‘pieces of eight’.”

A Troubling History

The line between piracy and the so-called privateers was not always clear and these latter included some dubious characters. Perhaps none more so than Henry Morgan (c1635-1688) who attacked Spanish allotments (meaning farms and plantations, not Grandad’s carrot patch!) in Panama in 1671. This was illegal as Britain and Spain were now at peace.

Incredibly, Morgan was knighted and made governor of Jamaica, then a British colony. He used the profits from privateering to invest in his sugar plantations in Jamaica, which were worked by enslaved people. Any idea of pirates as radical, free-thinking, all men are equal romantic rebels is likely far from the sad truth.

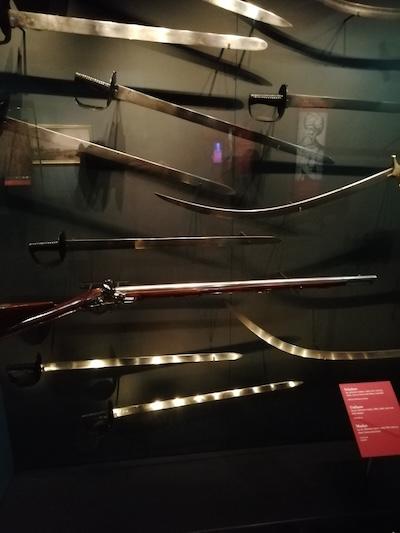

Listen, folks, I’m a pacifist but I have to say that we have some great weapons on display at various points around the exhibition, including a muzzle-loading smoothbore gun in brass c1700 and a cabinet of swords and firearms that includes powder horns (c1700), lead musket balls (eighteenth century), a brass and wood blunderbuss (C18) and a huge Boat Gun (C18) in brass, steel and wood—how could you lift and fire this monster?

Morgan and Bonny are outliers. Most pirates had a short career and a short life. From the 1720s onwards, governments and navies made a concerted effort to protect their shipping and trading interests. Pirates would be captured, tried and executed. Sometimes they would be made a deterring example—we have here, quite evocatively, a replica gibbet cage in which the body would be encased and left to hang publicly. This grim reminder marks the end of the second part of the exhibition. With the voiceovers and the wall information, I learnt a certain amount about pirates’ daily lives although maybe the museum could have gone even more full-on with a mock-up of a typical cabin or galleon deck—the sort of thing that the Imperial War Museum did for its Blitz experience.

Ruling the Waves?

One has to note that, historically at least, the National Maritime Museum has been founded at least partially on the song lyric “Britannia rules the waves”. The final section deals with piracy in other parts of the world—such as the Barbary corsairs from North Africa who captured ships in the Mediterranean and beyond. Also, how the seas around China, India and Southeast Asia were historically affected by pirates. This final third is a little less successful as it doesn’t don’t fit so snugly into the Johnny Depp Captain Jack Sparrow world so many know and love.

What we do quite consciously note, however, is that the British fleets have been present and prevalent in many waters way beyond our shores over the centuries. For example, there is a big display on the Bombardment of Algiers in 1816, led by Admiral Lord Exmouth and the British and Dutch fleet which put an end to raids on European shipping and the enslavement of Christians by shelling the port city of Algiers from the sea and killing between one and three thousand people. Quite movingly, the woollen Ottoman flag—red with three white crescents—is on display as a war trophy taken in the battle by Royal Navy lieutenant James Everard.

We move to South and Southeast Asia with more weapons on display and information about Tulaji Angre—grand admiral of the Maratha Navy 1743-54. Considered a pirate by local Maratha rulers, the Royal Navy and the British East India Company, he was captured and imprisoned in 1756. We have some more information on Chinese pirates of the 1800s, often centred around Canton port (now Guanzhong) and recorded by the likes of naval surgeon Edward H. Cree (served 1837-69) in his journals. Yep, Brits getting involved yet again.

Lastly, we come up to date with some information about modern piracy—recent news stories have focused on so-called “Somali pirates” targeting ships in the Red Sea. The museum goes a little way towards suggesting reasons why piracy is still evident, citing financial inequality as a possible driving factor.

Pirates? Really?

Interestingly, the final display invites us to consider the very definition of piracy. The United Nations has it as: “Piracy is an act of violence or robbery on the high seas. In many cases, these involve a vessel being boarded and taken hostage for large ransoms.” However, environmental action groups such as Greenpeace have also been tarnished as “pirates” by some governments and corporations for wanting to defend and preserve the fragile and endangered areas of our planet from exploitation. When does activism become criminality or piracy? The Greenpeace boats are a long way from the Hispaniola. Maybe we are more comfortable with the myth of pirates than the reality and maybe we need to consider just who the pirates really are, especially if greed is not their key motivation.

A very good exhibition. Lots to see and learn about and some good historical artefacts. Hand on heart, I think most visitors will probably come away still feeling that somewhat romantic pull of piracy. If you have time, there’s the rest of this world class museum to check out to get your fill of seaborne adventure and daydreaming. And talking of days, I would recommend turning up after 2pm so as to avoid any buccaneering groups of feral schoolchildren!

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, UK. “Pirates” Exhibition open daily from 10am to 5pm. Closes 4 January 2026. Adult tickets: £15. More details on the website.