Allen Ashley is training his eye on classic genre films for us, looking at not just the film but the context in which they were released. Here’s the latest instalment in his blog series.

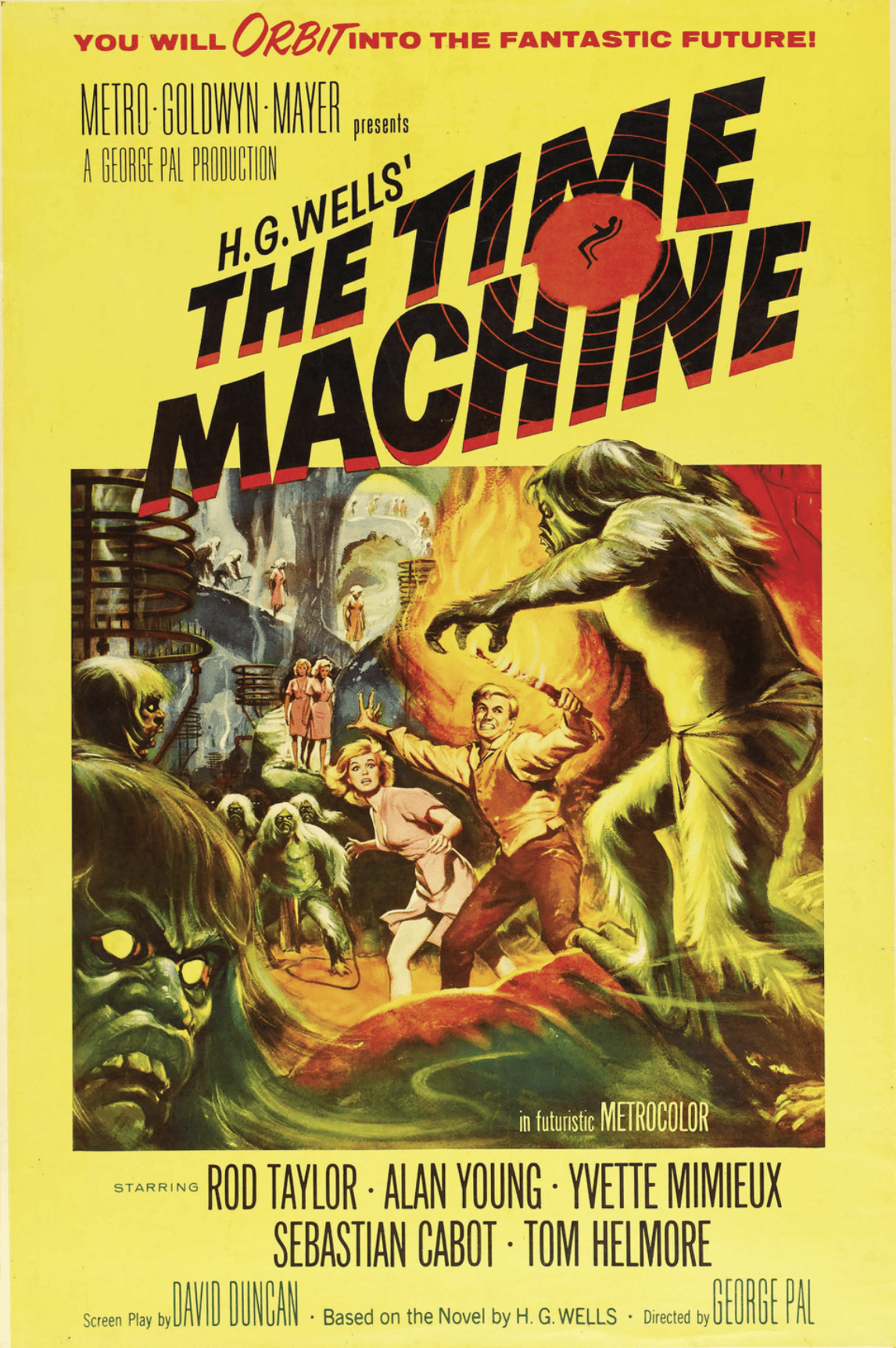

The Time Machine (1960)

Directed: George Pal

Colour

99 minutes running time (on DVD)

(All images taken from imdb.com)

(Note: Time stamps are of author’s own noting)

Nowadays, The Time Machine by H. G. Wells (1895) is considered to be a novella, but it packs more meaningful content into its short length than many a 1000-page saga. For such a seminal work, the only real surprise is that it has not been filmed more frequently. There was a version in 2002 starring Guy Pearce and Samantha Mumba, but it’s the 1960 iteration directed by George Pal that is under consideration here. This film is a treasure in its own right but was also destined to be hugely influential on televised SF over the succeeding decades.

In Wells’ book, the hero is simply known as “The Traveller” but in the film he is identified as “George”, ably played by Rod Taylor, with the implication being that he is actually Herbert George Wells, here cast as a well-to-do scholar and inventor.

What time is it?

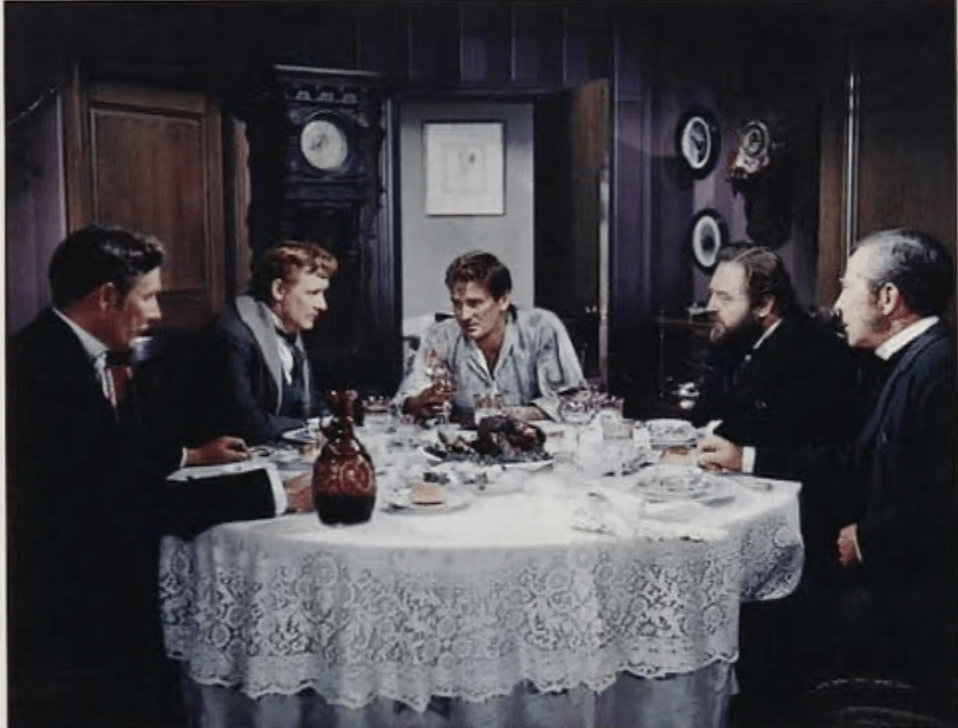

The movie has a framing device of supper at George’s house, prepared by the redoubtable Mrs Watchett (Doris Lloyd) and attended by George’s port-drinking and cigar-smoking circle of male friends, including David Filby (Alan Young). I’m not the biggest fan of framing devices – get on with the story and action is my mantra – but here its use offers a soft, slightly snowy blanket of late-Victorian London domesticity (New Year’s Eve 1899 and, later, 5 January 1900) bookending the life-threatening and, indeed, species-threatening drama that plays out as the meat in the sandwich.

We are also subtly introduced to the inherent paradoxes of time travel. At minute 5, as a dishevelled George crashes into the dining room, we learn that he has returned to his own time (our past) having journeyed into the future. He has reconnected with his friends on 5 January 1900 and what follows between minutes 6 and 25 is background exposition from the previous dinner on New Year’s Eve 1899 (his recent past).

The succeeding filmic events between minutes 26 and 92 detail George’s jump into the future that are being told to his companions on his 5 Jan 1900 return, that happened at minute 5. Thus: A recount of events experienced by George that are yet to actually happen.

All the time in the world

Just a few days have passed in the Victorian world, but George has journeyed thousands of years into the future before returning to relate his tale of wars, regression, social divisions and human survival to his disbelieving friends – with just a violet flower gift from love interest Weena (Yvette Mimieux) and the somewhat battered but still secret time machine as proof.

And it’s to Weena that George returns over minutes 95 and 96, with Filby and Mrs Watchett as aural witnesses to George’s departure. Mrs W embraces the romance of the situation – George has dragged the sled-like machine back into the house so that he can return to “right where he left her” (c97m) – and Filby muses that with such a device George “has all the time in the world” (c98m).

Time – the Fourth Dimension

For those of you who like a bit of philosophy and conjecture within the plotting… From about minute 6 to about minute 20 we get the now familiar speculation with lines from George such as, “Can he (mankind) change the shape of things to come?” (11m), and “I intend taking a journey into the future” (15m). Filby later warns George against tempting “the laws of providence” (19m).

This whole discussion about Time, the mysterious “fourth dimension”, received a different but similar spin a mere three years later as Verity Lambert and Co introduced us to the ground-breaking BBC TV serial Doctor Who, from the opening episode “An Unearthly Child” onwards. The titular Doctor, as played by William Hartnell, is essentially derived from H. G. Wells’ ‘Traveller’, complete with suit and waistcoat that would befit a well to do late-Victorian inventor. Without The Time Machine – book and film – there would be no Dr Who.

Ride on time

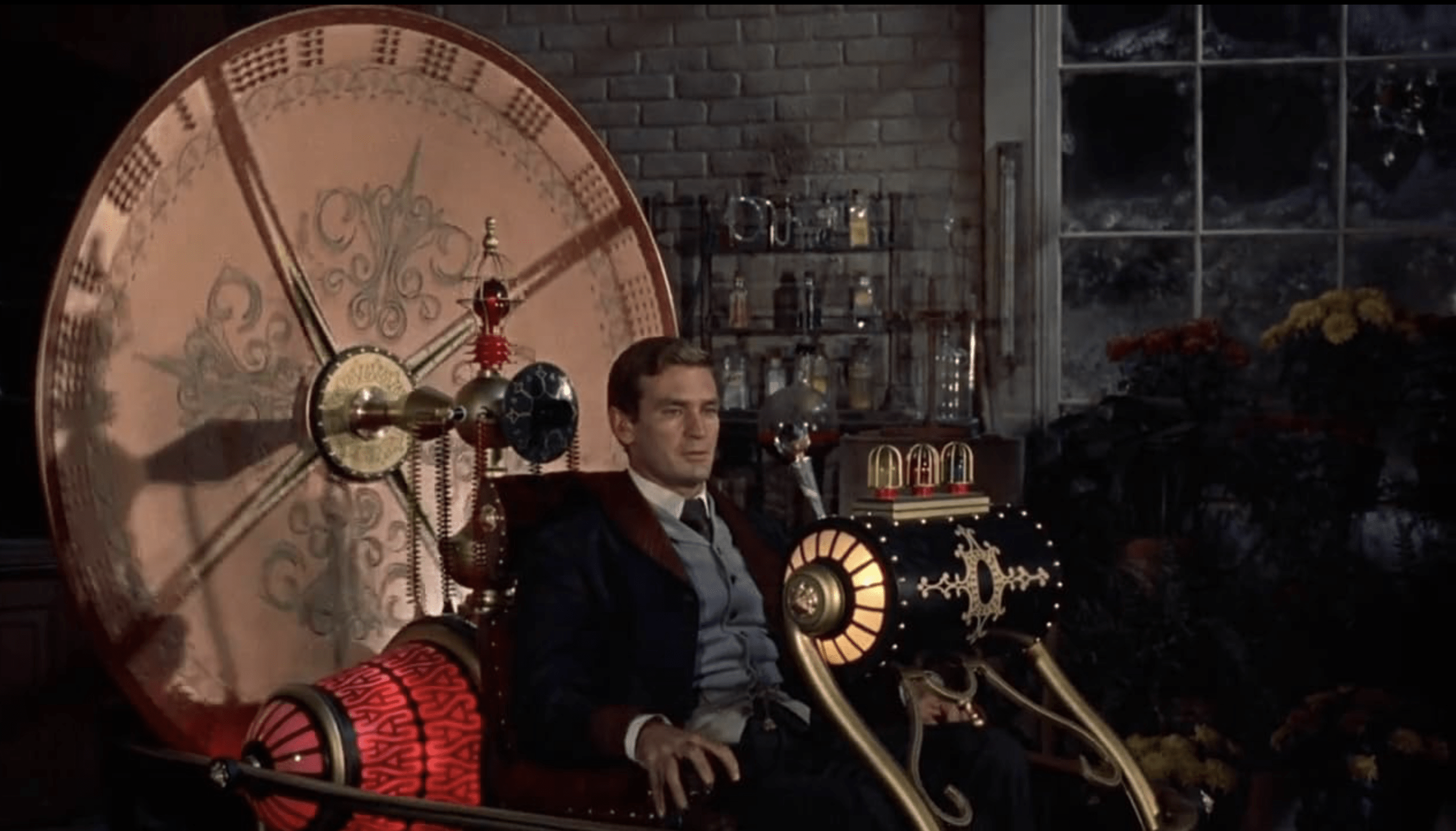

Let’s move on to the machine itself. In cinematic and filmic history, there are probably three absolutely iconic time travel vehicles. We have the DeLorean car in Back to the Future (1985); we have the blue police box TARDIS in Dr Who (1963 onwards); but predating both, we have George’s ergonomic Victorian-punk time machine, modelled to look a little like Santa’s sleigh with a spinning parasol attached to the rear. The colourful date display screen is extra-useful for viewers as George pitches up in 1917, 1940, 1966, and beyond. This fabulous prop is instantly recognisable to movie buffs and even made a guest appearance in an episode of the TV show The Big Bang Theory (“The Nerdwana Annihilation”, 2008).

Watching the world go by

The Time Machine won an Academy Award for its special effects, specifically for the utterly charming stop-motion depiction of time passing as depicted via the windows of George’s study. We have the sun moving across the sky; the diurnal and nocturnal; frost forming on the panes; the changing fashions on the female mannequin in the shop across the street. Film is still mostly a visual medium and these sequences are a delight to watch.

We have an affecting scene across minutes 31 to 34 as George pitches up in London during World War One and thinks he sees his old friend Filby but it turns out to be the now grown-up son, just back from the Front in France. And Filby Senior has died during the conflict. It’s a neat illustration of the paradox of a time traveller not ageing at all whilst those who actually live through the intervening years face age and mortality as per normal.

About a girl

The key, memorable action from the film, though, kicks in around minute 44 as George crash-lands his vehicle outside a mysterious temple far into humanity’s potential future. At first, he believes he has “found a paradise” (c45m) but a spot of theremin music at minute 48 and a disturbing incident in which he has to save a young woman from drowning (c49-51m) alerts us that Eden is not so easily reached.

The young woman is Weena, played somewhat controversially at the time by French model and non-actress Yvette Mimieux. Mimieux’s child-like demeanour and lack of stagecraft actually suit this casting as a far-future ingenue, representative of the somewhat brainwashed Eloi tribe. One can’t imagine, though, that Mimieux got any calls to play Lady Macbeth or Elizabeth Bennett on this showing.

All’s fair

The male members of the Eloi sport fair hair in a short early Mod style that was later largely replicated by the Thals in Doctor Who – The Daleks (1963). The Eloi’s pastel-coloured tunics later influenced the styling of the young population in Logan’s Run, both the film (1976) and the TV spin-off series (1977-8). These callow and naïve vegetarians are actually the somewhat unknowing captive prey of the evil grey-green skinned troglodyte cannibalistic race the Morlocks.

Our hero George – spurred on by moral purpose, lust for Weena and what we would nowadays describe as a saviour complex – leads the uprising of the Eloi against the Morlocks… although one inevitably wonders where their next plate of ripe fruit will be coming from. Now, this is a plot move that was to become quite familiar later in the decade as Captain Kirk from Star Trek, fists clenched and with an eye for the soft-focus ladies, regularly went against the Prime Directive and encouraged rebellion by the repressed native populations, even if that led to unanswered (and unasked!) questions of how do we rebuild our society and feed ourselves now, oh great Earth warrior?

It’s clear that Gene Roddenberry borrowed a lot from The Time Machine as he formulated the original iteration of Star Trek. As a particular exemplar, have a look at the series two episode “The Apple” (1967).

In The Time Machine, the Eloi are called, zombie-like, into the mysterious temple to feed the Morlocks. In “The Apple”, the ‘god’ Vaal resides in a remarkably similar construction that also leads to an underground complex. And the half-dressed, unsophisticated young natives are mind-controlled into following its orders and ‘feeding’ it.

Pictured: The temple from The Time Machine (top), and from Star Trek’s The Apple (bottom), show remarkable similarities.

Time’s up

I’m in the business of analysing and recommending old movie gems for your viewing pleasure. George Pal’s The Time Machine represents a high-water mark in the visual history of science fiction and is another classic to seek out or to catch when it pops up on the viewing schedules.

What did you think of The Time Machine? Let us know in the comments below ⬇️

One response to “Classic Genre Films: The Time Machine (1960)”

Excellent stuff indeed, although I do love a framing device.