Allen Ashley is training his eye on classic genre films for us, looking at not just the film but the context in which they were released. Here’s the latest instalment in his blog series.

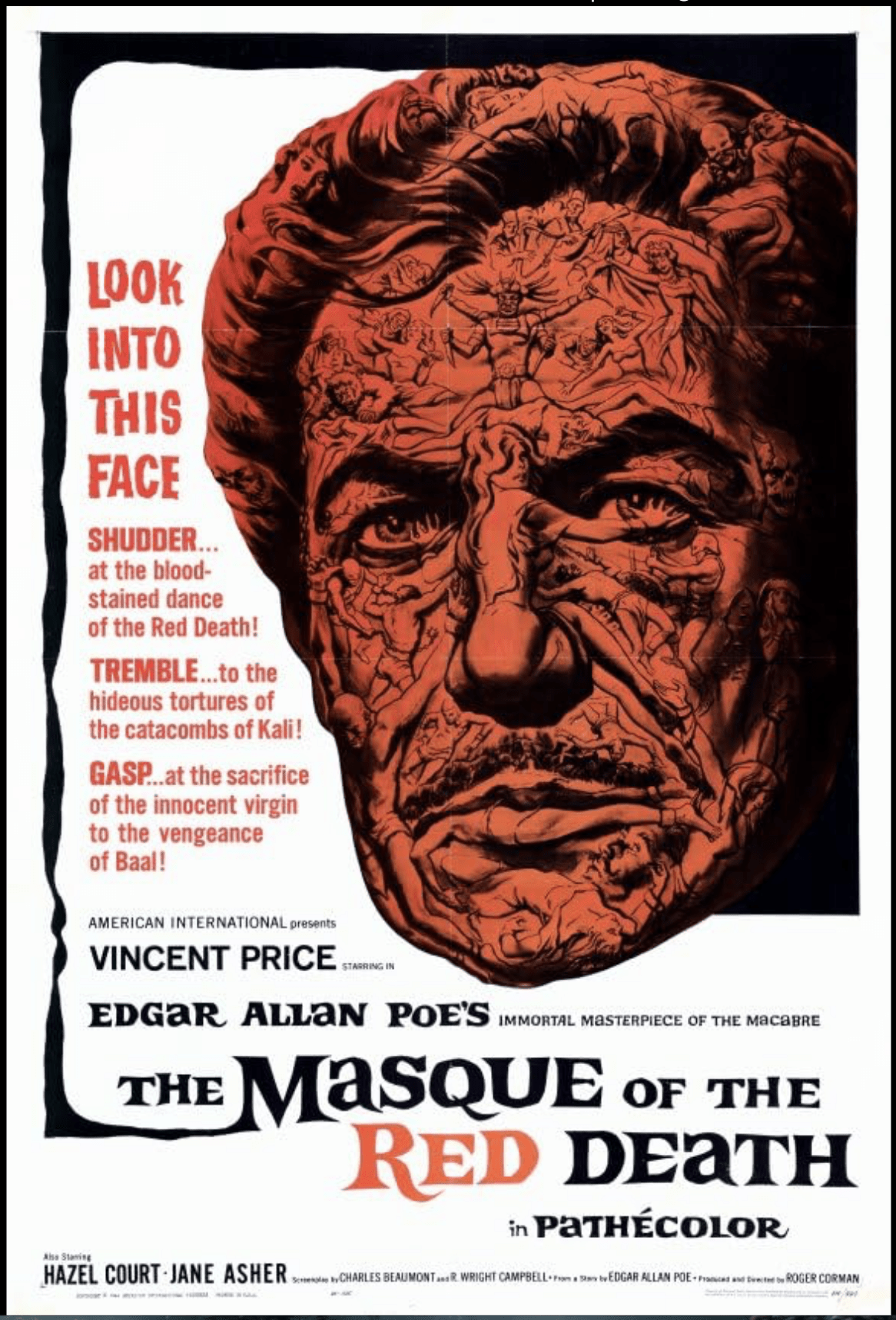

The Masque of the Red Death (1964)

Director: Roger Corman

Colour

87 minutes approx running time (on DVD)

(All images taken from imdb.com)

(Note: Time stamps are of author’s own noting)

I thought it was about time to focus on an out and out horror movie. So, a great place to start is with one of the cult classics that at the time was pigeonholed as a B movie, but which these days we would consider to be an arty indie. Director Roger Corman made eight films based on or inspired by the writings of Edgar Allan Poe—notable editions include The Pit and the Pendulum and The Raven (yes, a film essentially based on a poem, wow if only he had come calling…!). Today our focus is The Masque of the Red Death (1964), based on the short story of the same name, as well as incorporating other tales such as Hop-Frog. In glorious, occasionally gory-ous, Technicolor, this film is one of several that has the holy trinity for 1960s horror films—Poe, Corman, and lead actor Vincent Price.

The Price of Fame

Vincent Price has an acting style that is highly mannered and, in some eyes, overly theatrical. On occasion, that might seem inappropriate for the subtleties of cinematic projection, but here Price delivers a performance that conveys the complications and depth of the film’s dominating anti-hero, Prince Prospero.

Judging by the technological level, the ostensible time period of the film’s setting is somewhere in that regular fifteenth-sixteenth-seventeenth century CE common to many American International and Hammer horror films. At about minute 19, Prospero boasts of a Christian ancestor who became an inquisitor and tortured “600 men, woman and children”, so this would put us at least a century after 1478. But exact historical time can be a bit fluid in these pictures.

In early medieval style, evil Prince Prospero orders his helmeted and armoured knights to burn the village of Catania to the ground (c7m) and fire crossbows at unwelcome visitors (c66m) yet at times he pontificates on time, existence, religion and mortality like a warped Renaissance polymath, and indulges in the twisted philosophy more associated with the Marquis de Sade (1740-1814) than Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527). At one stage he almost echoes the teachings of self-professed twentieth century wizard of evil, Aleister Crowley (“Act according to your nature,” Prospero instructs, c 17m, echoing Crowley’s infamous “Do what thou wilt” aphorism).

This Charming Man

As in other Poe adaptations and similar roles, Vincent Price lets us know that his antihero character is still an urbane, educated, charming man. He contrasts neatly with the more surface level, 2D villain Alfredo (Patrick Magee), essentially Prospero’s unsubtle, lascivious sidekick.

And in the good and holy corner—because there is always someone pure and Christian to hold onto in this range of films—we have the captive peasant maid Francesca, played somewhat guilelessly by a very young Jane Asher. This was back in the day when she was dating Beatle Paul McCartney and long before she became famous for baking cakes.

I Like To Move It

Watching this film again after several years away from Roger Corman’s work, I started to notice just how much movement there was in it. Just like in golden age episodes of Doctor Who, the characters here are regularly traversing underground stonework tunnels and labyrinthine passages into the castle’s dungeons. On other occasions, they are spread across a massive banqueting hall—the set for which Corman fortuitously inherited from a recent production of the film Becket (1964). There’s a lovely panning shot at about 13 or 14 minutes which gives a real sense of how Prince Prospero could propose to keep all his servants and sycophantic guests safe within his palatial walls as the pestilential disease, the Red Death, raged in the countryside beyond.

Notebook next to me, I found myself writing: Much of this film is actually a dance. And not just the obvious penultimate, stagey dance of death scene but large swathes of it feel like an experimental improv ballet troupe asked to conjure up visions of decadence. And artistically this is a good thing. Wow, I thought, I’ve been really original here and I’ve got my hook for the article. Then I researched some reviews and found that Peter Bradshaw in a Guardian review of the Blu-Ray release back in 2021, characterised the film as “an expressionist horror-ballet”. Ouch. As an aside, he also noted how apt the piece seemed during what was the second or third wave of the Covid pandemic.

Colour Me Sinful

Then there’s the colour coded rooms. In the original story by Edgar Allan Poe there are seven such chambers, including ones tainted orange, blue and green. Perhaps for financial reasons or ease of plotting, in the film we have four connecting rooms—one in yellow, one in purple, one in white, and a black room with red-lit windows where the Satanic rites take place.

The director cleverly uses the perambulations through these divisions to power the plot, whether it’s innocent Francesca finding that curiosity is sometimes best not to be indulged or Prospero’s original love interest Juliana (Hazel Court) branding her own breast as she seeks to become a bride of Satan; or the late scenes as Prospero and Francesca chase the mysterious robed and cowled figure who will eventually bring multiple deaths to the interior of this apparent safe haven.

Hooded and Hidden

Ah, though, let’s talk about cloaks and cowls. A staple of horror films from this era as directors and scriptwriters explored Good versus Evil and the Nietzschean notion that God is dead. (In fact, according to Prospero, Lucifer killed Him). We first meet this haunting, red robed figure in a nocturnal forest where the wind howls and the trees are just bare twigs and branches. We later meet him and his fellows in different vestment hues at the very end of the film as these angels of death gather to tell of their sorry work.

Director Roger Corman was, of course, aware that Ingmar Bergman had set a template in his film The Seventh Seal (1957) with the black robed Death playing chess with the doomed hero. Changing the game but still an obvious echo, we have, at about minute 83, the personified Red Death playing Tarot cards with a young girl who survived when her village was wiped out.

But the iconography would continue onwards—Matthew Fisher, organist with Procol Harum, playing A Whiter Shade of Pale on Top of the Pops or Arthur Brown’s backing band on the televised version of Fire, in monks’ outfits, faces hidden.

The moment when Prospero pulls away the red monk’s face covering (c79m) was later echoed when Patrick McGoohan (“Number Six”) finally got to confront the mysterious Number One in the Fall Out final episode of cult TV series The Prisoner (1968). Then there’s the current BBC TV hot ticket—night, an owl hoots, there’s a haunted stately home and walking around sombrely and mysteriously in the shadows we have… The Traitors.

A Thing of Beauty

You’ll have read me say this before but The Masque of the Red Death is beautiful to look at. The costumes of the ill-fated revellers. The interior of Prince Prospero’s castle. The final scene of the death angels of the apocalypse walking single file through the dead woods. The four mostly private rooms where Prospero does his philosophising. All vividly shot in Technicolor by Director of Photography Nicolas Roeg, who would go on to repeat the imagery somewhat with the lost child in the red cape in Don’t Look Now (1973).

Then there’s a two minute dream sequence (c58-59m)—actually it’s very much a violent, not to say violating, nightmare—as Juliana is visited in her sleep by three demons: one resembling an Aztec shaman, one a cross between Merlin and Bluebeard, the last a priest from Ancient Egypt, and they dance around her prone, silently screaming body. All this is shot in a distorted, liquid teal and is quite unsettling.

Classic Gothic

Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death is as much intellectual horror as a death and gore fest. This film is a vivid celebration of the Gothic form. So many signifiers are there:

- A dark stone castle with dungeons and secret rooms

- Most of the action takes place at night

- The wind whistling through the open windows as Jane Asher’s character sleeps in a four poster bed

- An unexplained bloodstain

- Mysterious off-camera chanting in Latin; the early prophecy from the red-cloaked figure (“The day of their deliverance is at hand,” c2m)

- The fear and mistreatment of difference (as exemplified by the way that the dwarf Hop-Toad and the “tiny dancer” Esmaralda are considered to be freakish entertainment for the depraved guests)

- The allure of masculine evil as particularly personified by Prince Prospero

- The feeling that the setting is both medieval yet timeless

And, of course, the all-pervasive sense of inevitable doom, which links us back to the original classic short story, first published in Graham’s Magazine May 1842 but most familiar to us from Poe’s collection Tales of Mystery and Imagination (Everyman edition, 1908).

Like George Pal did with H.G. Wells, and like other directors have done with authors such as Verne and Lovecraft, Corman has majestically assured that Poe’s work reaches and delights movie audiences.

What did you think of The Masque of the Red Death? Let us know in the comments below ⬇️

Leave a Reply