As we celebrate half a century since the premiere of one of Australia’s finest cinema contributions, Gary Couzens takes a look back at Peter Weir’s film based on Joan Lindsey’s seminal novel.

What we see and what we seem are but a dream…

Opening lines of the film Picnic at Hanging Rock, quoting Edgar Allan Poe.

a dream within a dream.

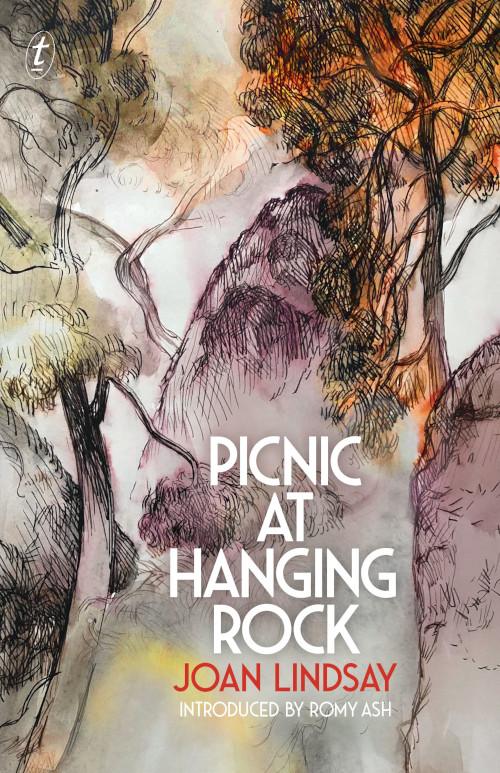

Picnic at Hanging Rock centres on a mystery, but contrary to our usual expectations it’s a mystery which is never solved. Based on Joan Lindsay’s novel, with a screenplay by Cliff Green, Picnic is a story about a mystery and its effects rather than a solution to it.

Mystery, unresolved, has a power that might be dissipated if a resolution is provided. The 1975 film, directed by Peter Weir, sets out its stall from the outset, with the following caption:

On Saturday 14th February 1900 a party of schoolgirls from Appleyard College picnicked at Hanging Rock near Mt Macedon in the state of Victoria.

During the afternoon several members of the party disappeared without trace…

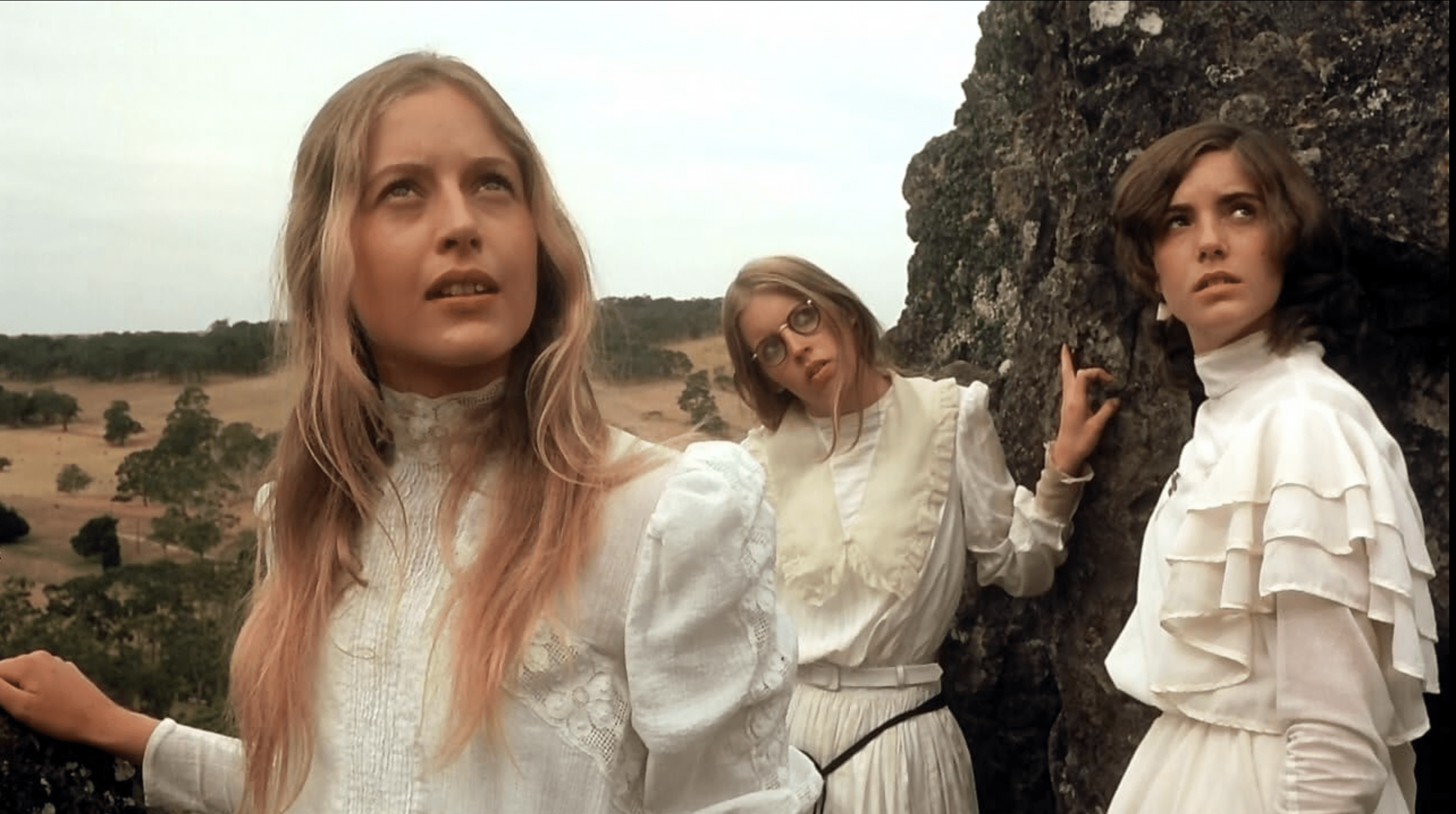

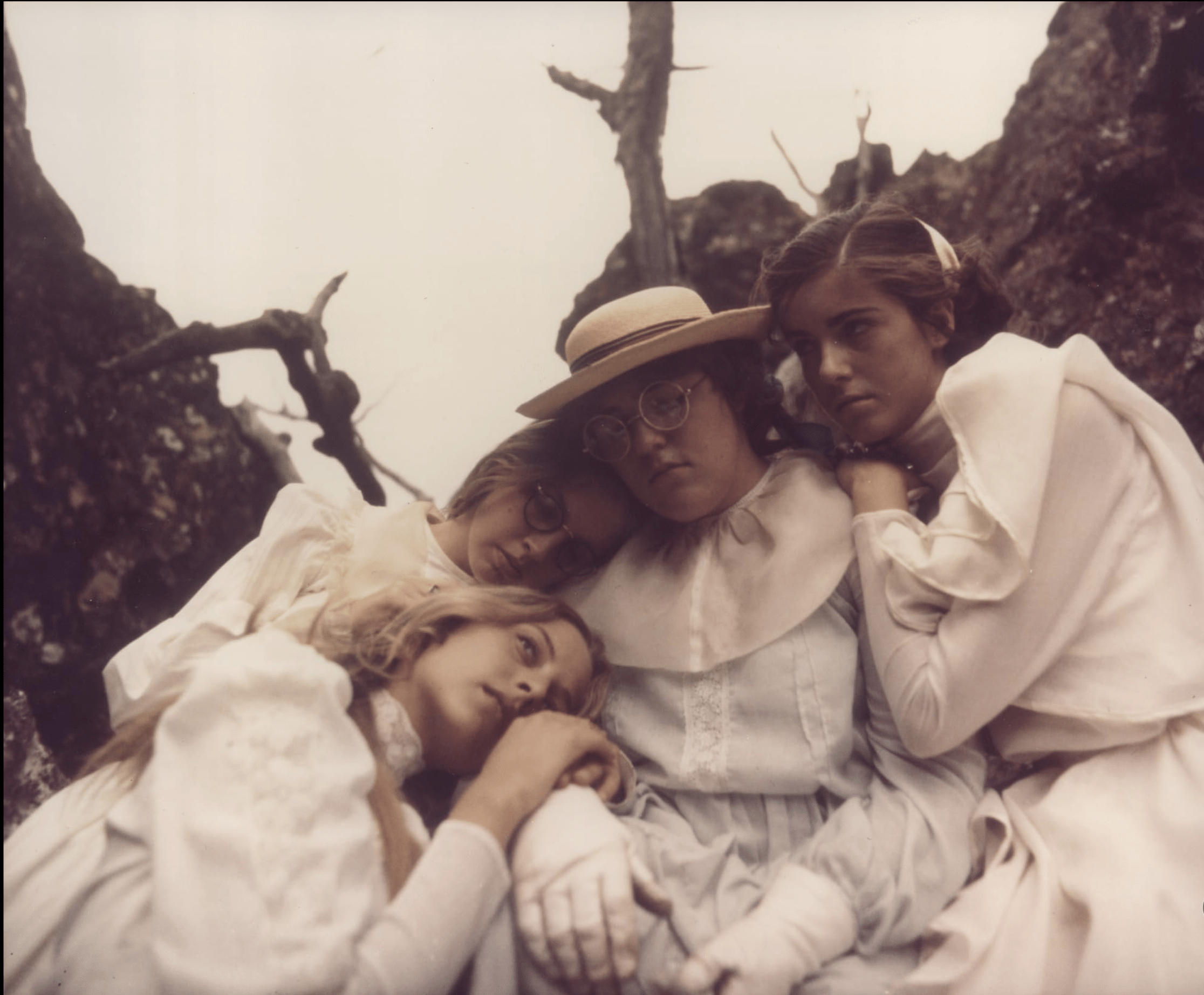

Those several members are three schoolgirls—Miranda (Anne Lambert), Marion (Jane Vallis), Irma (Karen Robson)—and one teacher, Miss McCraw (Vivean Gray). Irma is later discovered on the rock but the others are never found. Joan Lindsay hinted that her novel was not actually fiction, but instead an account of true events.

The novel begins with a two-page dramatis personae and the following author’s note: “Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is fact or fiction, my readers must decide for themselves. As the fateful picnic took place in the year nineteen-hundred, and all the characters who appear in this book are long since dead, it hardly seems important.”

In fact, the story is pure fiction – and, for one thing, 14 February in 1900 actually fell on a Wednesday.

Origins of an icon

Hanging Rock—officially Mount Diogenes, with its indigenous name being Ngannelong—is the centrepiece of a nature reserve in Victoria, about seventy kilometres north-west of Melbourne. It is a mamelon, formed by an outflow of magma some six and a quarter million years ago, and rises 105 metres above the surrounding plains. It was a local landmark for Lindsay, who was born in 1896 in St Kilda East and went to Clyde Girls’ Grammar School, on which she based the novel’s fictional Appleyard College. St Valentine’s Day was Lindsay’s wedding anniversary. The story of Picnic at Hanging Rock came to her in a dream and the novel was published in 1967. It’s short by today’s standards, around 60,000 words with seventeen chapters, written in third person with an omniscient narrator. Originally there was an eighteenth chapter, which explained the mystery, but Lindsay’s editor suggested it be removed, and it was.

Peter Weir’s film was not the first adaptation of the novel. Anthony Ingram, a thirteen-year-old filmmaker, obtained permission from Lindsay to make his own film version, which he shot at weekends. The sale of the film rights of the novel to producer Patricia Lovell precluded any other version, so Ingram’s film was never completed. However, about three minutes of footage has been included on DVD and Blu-ray editions of Weir’s film, with a commentary by Ingram. It’s not fair to compare an amateur production shot in 16mm black and white with a professional one shot in 35mm colour by one of the great Australian cinematographers of the time, Russell Boyd, but there are some striking similarities, largely due to using the same locations and camera angles.

Patricia Lovell was best-known in the 1960s as host of the ABC children’s television show Mr Squiggle and later became an interviewer on the current affairs programme The Today Show. In that capacity, she met Peter Weir, who had begun his career on television and by the end of the decade was making documentaries for the Commonwealth Film Unit. His debut fiction film was the half-hour Michael, the opening segment of the 1970 portmanteau feature 3 to Go. Michael won the Grand Prix at the Australian Film Institute Awards, which Weir won again with the next year with his fifty-minute film Homesdale, a black comedy set in a private guesthouse where the residents live out their fantasies. Homesdale convinced Lovell that Weir would be right to direct Picnic and she decided to produce the film herself. By this time, Weir had made his first full-length feature The Cars That Ate Paris (or The Cars That Eat People, as it was retitled in the USA), and he agreed to make Picnic.

A Dormant Australian Film Industry Awakens

Australia had made the world’s first feature film, the hour-long Story of the Kelly Gang (of which some fifteen minutes survive) in 1906, and films were made in the country into the 1950s—but other than foreign films shot on location, the local film industry had declined to almost nothing; no local film received a commercial cinema release between 1955 and 1969, and much of the local output was tiny-budget work shot in 16mm and largely shown in cooperatives. An overseas co-production shot in the country, Michael Powell’s They’re a Weird Mob (1966), had sparked a concern that there should be a local film industry, and two further co-productions, Wake in Fright (1970) and Walkabout (1971), gave further impetus to this.

The first commercial successes of this revival were broad “ocker comedies” such as Stork (1971), The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972), and Alvin Purple (1973), which took advantage of the relaxation of censorship. These films were popular with audiences but critics objected to their presentation of Australians as vulgar, chundering sex-obsessed drunkards. Picnic at Hanging Rock was a film which served notice to audiences worldwide that Australian cinema was a newly vital force.

Essentially, what might have been arthouse fare became the mainstream, and more usually commercial genre filmmaking was felt to be marginalised. Soon after, there was a reaction against what was seen as genteel costume dramas and against “social realism” in favour of “Ozploitation” movies, something which in the wake of the 2008 documentary Not Quite Hollywood remains fashionable nowadays. Picnic is sometimes tarred with the same brush, though it is not a work of “social realism” in any sense and is far from genteel, though is undoubtedly a family-friendly historical literary adaptation.

“Respectability” and Colonial Entitlement

It’s no accident that the fateful picnic takes place on St Valentine’s Day, at the height of the Australian summer. As we see the schoolgirls get ready for their day out, the soundtrack is filled with the whispering of teenage girls, passing confidences and gossip, forming passionate attachments to their friends. However, the society they and their college is in is a determinedly “respectable” one, a colonial society influenced by a Britain still ruled by the monarch that the states of Victoria and Queensland were named after. There’s a sense of colonial entitlement as Irma says the Rock has been “waiting a million years, just for us”. The Rock is a significant site to the Aboriginal population in the area, but the only glimpse of one in the film is a single shot of a tracker. (The 2018 miniseries increased the Aboriginal representation in the story.)

The college is even run by a British person, Mrs Appleyard (played by a British actress, Rachel Roberts, who took over the role when the original choice, Vivien Merchant, became unavailable due to illness). It’s a society where respectability, or at least the outward show of it, is important, and less respectable feelings lurk and seethe under the surface. It’s not hard to see the disappearance amongst phallic rocks as a kind of awakening of sexual feelings, taking the three missing girls away from this world. The teacher who disappears with them is a middle-aged spinster, last seen without her skirt on, wearing just her pantaloons below her waist. Meanwhile, Mrs Appleyard—Mr Appleyard is deceased—is a woman who has repressed her own sexuality, and this comes out in her treatment of Sara (Margaret Nelson), an orphan kept at the college by an anonymous benefactor. As the mysterious disappearances become headline news, not just in Australia but elsewhere, Mrs Appleyard’s façade crumbles and her college with it, as families begin withdrawing their daughters from it.

A History of Mysteries and Mid-Century Arthouse Cinema

The classic example of a film about a mysterious disappearance is L’avventura, directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, which caused scandal at its premiere at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival by not resolving its mystery. A group of friends are on holiday on a Sicilian island and one of them disappears. She is never found, and while the search for her dies away, the film explores the relationships of those left behind. Mystery has power, and this is a film about the effect of that mystery, just like Picnic is. While the audience for a film like L’avventura was relatively small (of the size you might expect for a foreign-language film), it was still an influential one, not least in the number of filmmakers who brought the same techniques into films more widely seen. (While it’s not known if Joan Lindsay saw L’avventura, it did have its effect on literature as well: John Fowles’s novella, The Cloud, the final story in his collection The Ebony Tower and also a story involving an unexplained disappearance, directly alludes to it. There may be a nod in Picnic too, when Edith, the last to see the missing girls, mentions seeing a red cloud in the sky.)

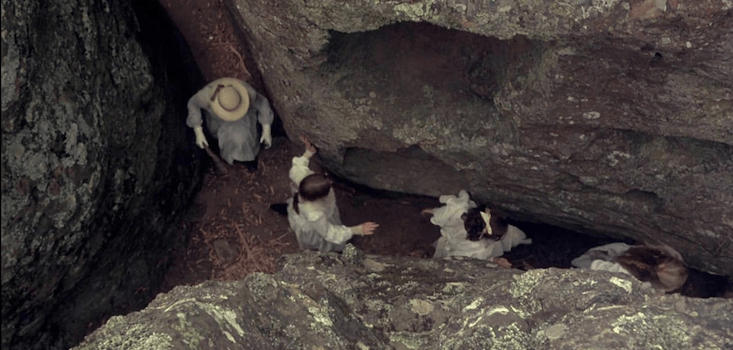

Weir’s film draws heavily on arthouse cinema protocols in its use of superimpositions, slow motion, and a final step-printed tracking shot across the girls at their picnic. It’s a film where you remember the atmosphere more than anything else: the summer heat, the not-always suppressed eroticism. This is aided no end by Boyd’s cinematography, which won him a BAFTA Award: he fixed a wedding veil across the camera lenses to diffuse the image. The soundtrack plays a part too, not just Georghe Zamphir’s panpipe theme (and what is Pan but a god who brings disruptive and often sexual feelings to the surface?), but by the sound effects, notably the ominous bass rumble as the soon-to-vanish girls climb the rock, as if an earthquake is about to happen. At the fateful time of noon, clocks stop, and at the end of the film, a ticking clock halts and Weir freezes a close-up of Mrs Appleyard.

On Location

While the scenes at Hanging Rock were shot on site in Victoria, other locations and the studio work were filmed in South Australia. Martindale Hall, near Mintaro, provided the exteriors of Appleyard College.

Picnic premiered in Adelaide on 8 August 1975. The film was a considerable success in Australia and the UK. It was less so in the USA, with the lack of a solution being a sticking point in a more can-do culture. Weir went on to make The Last Wave, another film where strange forces arise, in a contemporary Sydney setting this time, and another open ending.

In the 1980s, Weir was, like many of the leading directors of the Australian Film Revival, enticed overseas to work in the USA. (You may know him as director of films such as The Truman Show, Dead Poets Society, and Master and Commander.)

Joan Lindsay (pictured) died in 1984. Three years later, her deleted final chapter of Picnic was published as The Secret of Hanging Rock, and we learn that the three girls and their teacher disappeared through a hole in space and time. It’s an interesting pendant to the novel, but you sense that the editor was right to remove it.

In 1998, Weir (pictured) prepared a director’s cut of Picnic, which is unusual for a director’s cut in being shorter than the original version. Much of what was removed is a subplot where Michael (Dominic Guard), having helped to find Irma, becomes close to her and tries unsuccessfully to find out what happened. This does have the effect of tightening the second half of the film but does sideline Michael to the point where Guard’s second billing is less justified. More recently, the film was remastered in 4K resolution, supervised by Weir and Boyd, and UHD and Blu-ray editions of this include the original Australian theatrical cut (118 minutes – the international release ran 115) and the director’s cut.

In 2018, Picnic was remade as a six-part television miniseries, first broadcast on Foxtel in Australia. Three times longer than the film, it delves further into the back story of Mrs Appleyard (Natalie Dormer, thirteen years younger than Rachel Roberts was when she played the role), and expands on the tensions, platonic and otherwise, between the schoolgirls. A handsome if overlong production, it doesn’t disgrace its source and its famous predecessor though also doesn’t replace them.

In 1975, Picnic at Hanging Rock was one of the first films to bring international attention to a national cinema industry which was reviving after a couple of decades in the doldrums. It’s also the work of many major Australian talents, both in front of and behind the camera, who have gone on to significant careers at home and abroad. Picnic has also had its legacy: the British film The Falling, directed by Carol Morley, shares some of its hothouse girls’ school atmosphere and was avowedly influenced by it. But in its way Picnic is a one-off, a film not easily repeated: an arthouse film which became a popular success, one where the mood and atmosphere are palpable. Mystery has power.

This is a revised and updated version of “A Dream Within a Dream: Forty Years of Picnic at Hanging Rock”, published in the 2015 Fantasycon souvenir book, edited by Peter Coleborn.