As the final share for Neurodiversity Celebration Week , it’s time for my own—yes me, the person whose image floats above the guests posts on this blog. I promised the others I’d share mine if they shared theirs, so here we go: an “unpublished author” talks about how an ADHD diagnosis blew the lid on her troubles with writing.

So we’ve been sharing a few personal stories from BFS members in the last week as part of Neurodiversity Celebration Week, and I’ve been feeling a bit guilty. Me, the volunteer BFS Publicity Officer, the one who’s been sliding into feeds and saying “hey, I’d love to hear your story!â€â€”well, I also have a ND story to share. My brain has spent the last few days on a loop, telling me that I’m hiding, that I need to own it, that I shouldn’t expect others to put themselves out there if I’m not willing to do the same thing.

Humans of the internet, my brain has won. Eventually, at least. It’s currently looming on 7pm on Sunday 24 March, the final day of the Official Week, and I’m finally sitting down to write the blog I’ve been avoiding ever since I had the awesome idea of asking members to share their stories for the Neurodiversity Celebration Week. I need to do this. I have to do this. I should do this.

Reader, I’m struggling to do this. Because like C.L. Hellison, I am plagued by Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD). Because like David Green, I’ve had a lifetime of working hard to appear ‘normal’ and accepted. Because like E.M. Faulds, I began to suspect my neurodiversity only recently, after a lifetime of being called a dreamer, disorganised, constantly late. And like Kit Whitfield, the understanding that came with that idea was life-changing. And it’s on a scale I’m still trying to process.

Yes, I’m still trying to process it, this diagnosis of mine: that I have inattentive type ADHD, that I have dyspraxia, that I have autistic traits, that I have sensory processing disorder. Turns out my chronic depression and anxiety, my lack of self-worth, were likely symptoms of all of that going unnoticed. Eight months after the bit of paper landed in my inbox explaining all of these things, I’m only just starting to realise what it means for my identity. Not that I’m desperate to proudly assign myself to yet another label and community—far from it; I’ve always felt like an outsider who touches on multiple places, never quite fitting in to any of them. It’s that the things I’ve always been told have been turned on their head.

My desperate need to be accepted and fit in? Well, that’s part masking, part RSD, part just general human nature. My habit of constantly falling down the stairs, of injuring myself in both inane and extreme ways? That’d be the dyspraxic issue with spatial awareness, not that I’m a clumsy idiot. My inability to grasp how long something actually takes, whether it’s work or travel? It’s ADHD time blindness, not disorganisation or laziness. My weird thing about food texture or having clothing tight around my neck, or the fact I can’t listen to podcasts or audio books? Both of those are sensory processing disorder, not a personal oddity that I need to apologise for. That tendency to interrupt people while they’re speaking? Well, that bit is definitely the ADHD and probably not, maybe, just that I’m selfish and need to make it all about me. Most of the time, at least.

(Pictured left: the author’s most recent dyspraxic event resulted in her sporting a moon boot and crutches for several months.)

I’ve been on a real journey in the last few years, trying to figure out who I actually am, what I actually want to be doing, after two decades—heck, let’s be honest, an entire lifetime—of just rolling along, only paying attention to what’s right in front of me, forgetting things all the time and generally feeling like a terrible friend, family member, partner. Because the other thing the diagnosis said was that I’m “high-functioningâ€, which is just the medical way of saying I’ve masked it so well that when I now talk about these things, I get a look that says “yeah, bullshit, you’re jumping on a trendâ€. At least, that’s what the RSD tells me. The RSD that meant former bosses would tell me they were too scared to talk to me because I always looked like I was on the verge of tears. The RSD that stops me doing what I want to do the most, which is what much of our community wants to do most: CREATE.

And this is what I really sat down to write about, dear reader: the impact that undiagnosed neurodiversity has had on me as a writer, and what the diagnosis is doing to me now. And in that very ADHD way, I’ve already spent an entire page-and-a-bit of a Google Doc rambling about nothing in particular.

Let’s get to the point, shall we? Unlike the other BFS members who’ve shared their stories, I’m not a published author—at least, not in the sense of having a book out there, or short stories in magazines. I am one of the many members who still have it as their dream, an absolute dream goal, to be one of those people.

(I’ve been told many, many times I shouldn’t call myself ‘not published’ given I’ve spent 30 years as a journalist and content writer for the day job, and given I’ve had some competition successes and the odd thing appear in community anthologies, but I think at least a few of you will understand what I mean by this label.)

(Pictured right: one of the community anthologies to which the author donated an old story—Tales from the Ether, edited by Warwick Writers.)

That’s not because I haven’t thought about getting published, haven’t tried to put myself on that path. I have, I really really really have.

My 30s were spent declaring THIS IS IT, this is the time I take it seriously. I’d get new notebooks and pens. I’d make plans, or try to make plans. I’d set myself goals, both big and audacious and small and manageable. My last effort? I got myself a specialised writing desk made from reclaimed industrial wood, telling myself that would be the key, the thing that would make it happen (and which currently is covered by detritus).

(Pictured left: some of the many shiny objects the writer has purchased to “help her write”, sitting on the above-mentioned desk.)

Reader, I have SO MANY half-started stories and a few novellas that maybe might have something? I have at least two first draft novels that were done as part of one of the many, many writing courses I sent myself to, and which I abandoned as soon as the course was over. Oh god, the amount of money I’ve spent on writing courses is ridiculous. It could redecorate our house, honestly.

And then I burned out. I had a sort-of breakdown during the pandemic. I just couldn’t deal with anything anymore. I stopped doing everything and anything. At least, that was the plan; I ended up doing a coaching qualification instead of resting. Because ADHD won’t let me rest, nor look after myself as I need to.

It was, however, during my recovery time that I learned about RSD while working for a mental health charity (what rest?!). I heard more about ADHD, read more about it, and started to recognise myself.

And as I started to see myself in these traits, I started to realise something:

It wasn’t my fault.

It wasn’t a failure on my part. It was just that I was desperately trying to force myself to behave like a neurotypical. To write according to established societal norms. To listen to the accepted wisdom about How To Be A Writer. All of which didn’t work for me, a neurodiverse person.

I used to be a very visible part of a writing community that espoused the virtues of “turn up to the page every dayâ€. I tried so damn hard to force myself, a square peg, into that round hole. I was an active member who really tried to do all the goal-setting, all the progress reports, all the good little neurotypical things that worked for everyone else. And I’d have to turn up at the end of every week and make excuses: oh, I wasn’t well this week, it was super busy at work, it was blah blah blah. After a while, I started calling myself the Queen of Procrastination, because as I saw everyone else progress, get through first drafts, then edits, then start querying, land agents and book deals and the whole rest of it, I started thinking I was just a failure. That this writing thing wasn’t for me.

My diagnosis showed me otherwise.

Reading about other neurotypical writers—especially in our fabulous genre fiction communities—showed me that it was possible to write in other ways. To create at your own pace, to your own rhythm. That, obviously, the comparison demon needs to be defeated first, but that it’s not my fault, and it’s not that I can’t do it.

I just need to find the right way. For me. And we’re all different.

I’ve been through the advice wheel of “just make time for itâ€, of “block out your calendar and colour code itâ€, of “you just need a scheduleâ€â€”but I know that any sort of schedule makes me feel hemmed in and anxious. It’s a sure-fire way to make me run.

I also know intimately that setting goals won’t work for me, because I’ll just watch them as they fly by. (I once publicly declared on a podcast that I’d have my first draft novel done by the end of the summer because it had been taking me “too longâ€; that was over a year ago and it’s still not even started.)

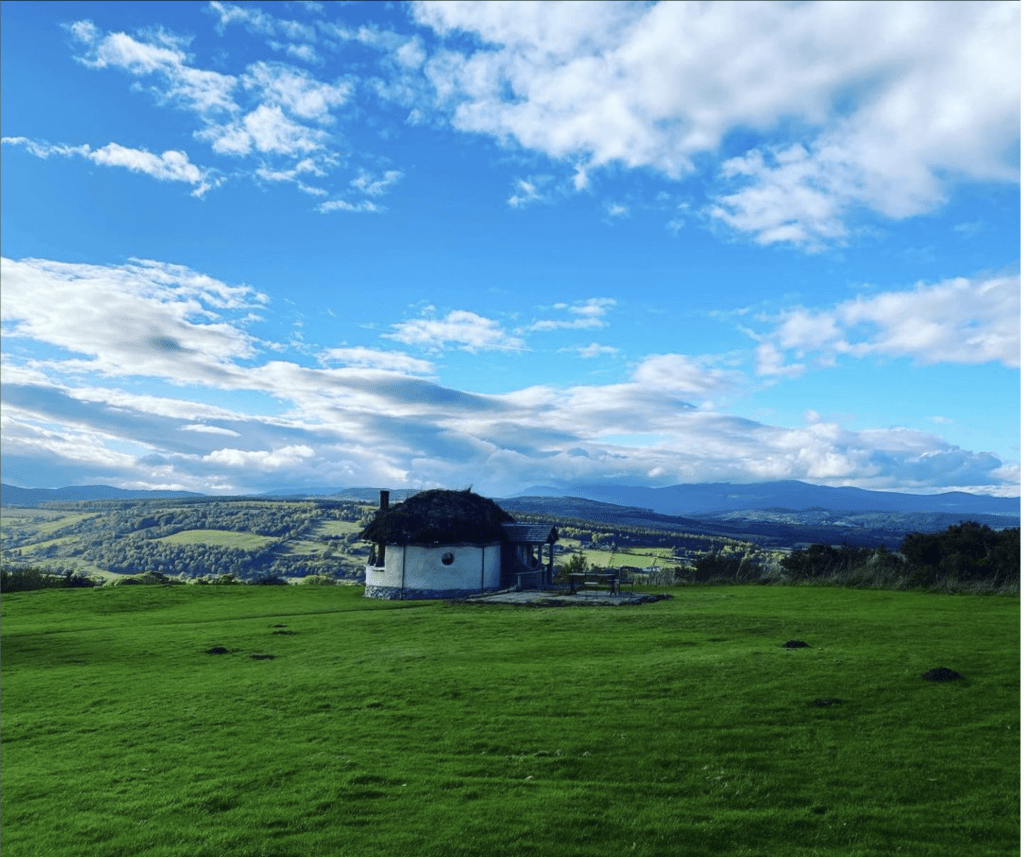

The “show up every day†thing doesn’t work for me, but I do know that the one time I went on a week-long retreat I got so fired up and inspired by being surrounded by creating that I was beaming. Maybe I’m just someone who needs a long stretch of uninterrupted time to get it done? That’s an experiment I’m looking forward to.

(Pictured right: Moniack Mhor in the Scottish Highlands, where the author spent a week a few years ago.)

I get the same feeling when I attend a genre con, which is still quite new to me, and I know it’s something I want to do more of—come to think of it, that’s probably why I started organising my own online event days under the Writing the Occult banner!

But I also know that, until I understand more about myself and about my needs and about what works for me, it’s fairly pointless trying to make declarations of intent, either publicly or privately. I need to process more, to experiment more, to take the pressure off myself to write and create.

Sometimes pressure doesn’t create a diamond. Sometimes it just drives the beauty away, deeper within, until it’s unwilling to come out and play. I need to find my own way to coax it forward. To play.

Keep dreaming.

And until then, I’ll keep processing, keep figuring it out, keep experimenting. After all, that is the very nature of creating, isn’t it?